And two more illustrated folktales by Ryan Sinon

And two more illustrated folktales by Ryan Sinon

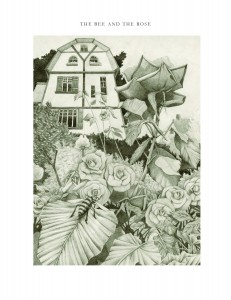

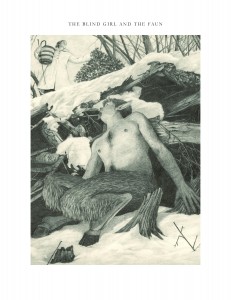

In the heart of an old pine forest there lived a young Faun who was quite proud of his goat legs. They were tightly muscled and covered in brown fur. Whenever the wind blew the fur moved like grass in a field. He walked with a purposeful gait, chin forward, eyes alert, and at the slightest sound his long, felt-like ears flicked to attention like a pair of soldiers. His bare chest was the color of a hen’s egg, and equally as smooth, except for a diamond shaped tuft of hair at the center.

A small, curling beard grew from his chin and in the recent months, the hard lines of his jaw began to define themselves. In the forest lakes, he noticed changes in his reflection, especially the length of his horns, which, although still short, seemed to protrude more and more sharply from either side of his forehead.

The Faun was caretaker of a garden hidden in the heart of the forest. He was the only one who knew the way and was certain it would never be discovered because the wooded path forked so many times and twisted in so many different directions it was easy to get lost. Winter was forbidden from entering the garden and so it was always Spring; and inside grew every variety of flower in all the world. The air was scented with hundreds of fragrances and the ground was covered by so many different colored blossoms it was difficult for the eye to choose where to rest–they were all so beautiful. Whenever the Faun passed by a particular bed of soil, the flowers growing there all straightened their stems and opened their petals towards him like an audience of colorful, upturned faces.

But he was the only one of his kind and as the years passed by he grew lonely and spent much of his time away from the garden, wandering through the woods. One day he came to the forest’s edge, where the tall pines butted up against a recently tilled cornfield. Across the field stood a quaint farm house, built from wood and painted red, complete with a small, fenced-in yard full of chickens. A young girl and her mother stood ankle deep among the birds, each holding a tin pail full of seed that they scattered handfuls of across the ground. The scene was lovely, but most lovely of all was the young farm girl. The shiny tin pail reflected a white light up onto her cheeks. She wore an apron, tied at the waist with a checkered red sash and on her head was a matching scarf done up in a knot to keep her hair off her shoulders. Even from across the cornfield, the Faun saw the soft blonde curls at the nape of her neck. After they’d finished feeding the chickens, the girl picked up a willow cane and, tapping the ground before her feet, made her way towards the farm house. It was then the Faun realized she was blind.

“I’m sure she’d make a wonderful friend,” he thought. “Because she can’t see, my legs won’t make any difference to her. She’ll think I’m a boy like any other.”

The Faun visited the same spot each day, where the pines met the cornfield, and each day he gazed out towards the farm house, waiting for his chance to make the young girl’s acquaintance. But the opportunity didn’t present itself until months later, when a severe frost blew in unseasonably early.

One morning, after an evening of heavy snow, the farm girl stepped out from the house, crossed the yard, and headed towards the pine forest. The Faun, looking out from his usual spot, saw she was dressed in a long coat sewn from white rabbit pelts. She nearly vanished into the wintry landscape, except for her cheeks which were pinched red from the cold. In her left hand, she carried a wicker basket and in her right, she tapped her willow cane along the snowy ground to keep from bumping into things. Closer and closer she came to the edge of the forest and when she was only a few feet from where he stood, the Faun grew frightened and hid in a shallow ditch. She stopped at the forest’s edge, where red berries hung in plump bundles on a bush. She was less than ten paces from his hiding place, and his keen nose picked up the scent of burnt wood still clinging to her from earlier that morning, when she’d warmed herself in front of the fireplace.

She wore fingerless gloves, and her pink fingertips felt along each branch, plucking berries and dropping them into her basket. The Faun could distinguish every detail of her bright young face and everything about her – every movement – entranced him. But as the chilly air stung her fingers she suddenly lost her grip on the wicker handle and she dropped both the basket and her willow cane. When the basket hit the ground the precious berries bounced out and disappeared beneath the snow without a sound. She knelt down and patted the ground in front of her, searching, but the cold was too intense and she quickly cupped her hands to her mouth and blew warm air into them.

At that moment the Faun peeked up from his hiding place and, seeing her kneeling in the snow with the basket toppled nearby, stood at once and softly cleared his throat, to let her know he was near; but despite his efforts, she gave a sudden start, her face quickly turning in the direction of his voice. “Who’s there?” she asked.

“I was passing and saw you,” he said. “You’ve dropped your basket.”

He approached her slowly and when he was within arms reach, knelt down next to her and flipped the basket right-side up. The scattered berries were easy to see, like drops of blood on a white sheet.

“Thank you,” she said, listening to him drop the berries, one by one, back into the basket; but her politeness was cold, and he could see she was uncomfortable about his sudden presence beside her. Her eyes seemed to be continually rolling in circles beneath her lids, and despite the freezing snow and her still burning fingertips, she reached out both hands to help search along the ground, as though eager to hurry everything along and be on her way. In her haste, she brushed her hand against his, and in doing so, a faint portrait appeared in her mind of what he might look like, drawing clues from the sounds of his movements, his smell of the outdoors, and the few words he’d spoken to her, so that by the time they’d finished filling the basket, she guessed him to be near her own age, nervous and enthusiastic, with an open, naive expression.

She stood up from the ground, lifting the basket with her. The Faun also stood, brushing snow and dead leaves off his furry legs. During the momentary silence that fell between them, she perceived his eyes on her, and unconsciously placed her hand inside the basket, stirring her fingers round and round. “Thank you again,” she said, then half-curtsied and turned around to head back home, only to realize in a flash of panic that she’d never retrieved her walking cane, which, having fallen with the basket, lay somewhere beneath the snow; and although it would have been easy to ask the boy to fetch it for her, she was too embarrassed and too proud, and pretended to step forward with a sure and confident stride; but then, in the next instant, she heard his voice and a wave of relief passed over her as she turned to face him once more.

“They’ll make you sick if you eat them,” he said.

What’s that?” she asked.

“The berries,” he said. “They’ll give you a sore stomach.”

“Oh, they’re not for eating,” she said. “Papa’s crop got killed by the frost, so Mama and I are making Christmas wreathes to sell in town for extra money. Most years we tie roses into the pine, but the blossoms died early, like the crops. Mama says wreathes with roses always sell quick, but the berries will have to do.”

“Listen,” said the Faun, “the cold hasn’t reached my garden yet. From the flower beds grow the reddest and most fragrant roses. Come back tomorrow and I’ll bring you some.”

At hearing the offer, a sudden excitement flashed across her face, only to vanish just as quickly. “But I can’t pay for your roses,” she said, “not even one.”

“Nevermind that,” said the Faun. “It’ll be my favor to you.”

She smiled, unable to mask her shame, and agreed to meet him in the same spot tomorrow. Before leaving she asked for her cane, and the Faun, looking down near his hooves, found it slipped beneath the snow. He picked it up and placed it into her open hand. She thanked him again, this time sincerely, then turned, making her way back across the field towards the farm house.

That evening the Faun returned to his garden deep in the forest. His shadow, crisp and black, danced before him as he clopped along the brick path, bordered by blossoms. When he came to the rose bush, he turned to the Roses and said,

“Today I met a young girl at the forest’s edge. She’s beautiful and asked me to bring her roses.”

Every rose believes she is the most beautiful among her sisters, and is too ashamed to wither and wilt. It’s not in their nature to grow old and lose their petals. They prefer being cut at the height of their beauty. So, of course, they all fought for a chance to be included in the Faun’s bouquet.

“A pretty young girl deserves only the best,” the Roses said, and stretched their necks upward to be cut.

With a short knife, he cut five stems, and with each cut the Roses let out a soft breath before falling into his palm. The next day, he traveled back through the woods to where the pines met the cornfield. There, the blind girl waited and when she heard his hooves crunching the snow, she turned her face towards him and said, “Boy, is that you?”

“Yes,” he said. “And here are the roses I promised.”

He held out the bouquet and she clumsily took the roses into her arms with a fumbling gesture; but in the next instant, her hands became suddenly sure of themselves, and she cradled the bundle as though it were an infant, her searching fingers gently grazing the thorny stems.

“Oh, thank you,” she said, “they’re wonderful!” She lowered her nose until it touched the soft blossoms and inhaled their sweet fragrance.

Despite the chilly air, the Faun felt suddenly warm at the sight of her happiness, and for the first time in his life was ashamed of his goat legs, wishing, more than anything else, he had legs like the girl.

“Tomorrow I’ll bring you more,” he said.

“No! Your garden will be nothing but stems,” she said. “Besides, it’s unfair. I’ve nothing to give in return.”

“I don’t mind,” he said, and she suddenly perceived a tenderness in his voice she’d not noticed before. The picture she held of him in her mind changed, and a blush, equal to the red of the petals, appeared in her cheeks and her fluttering eyelids suddenly lifted for a brief instant, revealing her milk white eyes.

“Tomorrow then,” she said, and quickly turned back towards the farm house, carrying the roses in the bend of her arm and tapping her cane across the snow.

He returned to his garden later that day. When he inhaled the sweet air, a hundred different smells filled his nostrils; but when he thought of the farm girl, a heavy sadness weighed on his heart.

“What’s wrong?” asked the Lilacs. “Usually you run along the path and your hooves spark against the brick. But today you look lost and your hooves clop softly.”

The boy knelt close to the bush and, cupping the flowers in his palm, said, “I’ve grown to love the young farm girl who lives near the edge of the forest. But she’s a girl and I’m a faun.”

“Bring her to this garden,” said a patch of Daisies, who were craning their stems to listen in on the conversation.

“Yes,” said the Begonias. “Bring her here and if she truly loves you as deeply as you love her, then the garden will grant you one wish. It’s only fair since you have cared for us for so many years.”

“My wish is to be like her,” he said. “To have feet instead of hooves; skin instead of fur; a pair of round, pink ears; and a smooth forehead without horns.”

“Invite her here,” said the Roses, “and as you lead her down the path, we’ll sense what secrets live in her heart. We roses know all about love. If she truly cares for you, then your wish will be granted.”

“But remember,” said the Rhododendrons. “The magic only works if she loves you back. Otherwise, it’s not meant to be.”

The following morning, the Faun traveled back through the wood to where the pines met the cornfield. There, the blind girl waited. He gave her five more roses, which he’d cut the night prior, and she accepted them with a bright, smiling face.

“Come with me to my garden,” he said. “It’s not a far walk from here.”

“You’ll have to lead me by the wrist,” she said, and held out her arm. The Faun did as she asked and led her deep into the forest. When they reached his garden, where Winter was forbidden and it was always Spring, it was so pleasant beneath the sun the farm girl removed her fur coat and hung it on a tree limb. Then the Faun led her along the brick path, softening his footsteps for fear she might hear his clopping hooves. All the flowers fanned their petals like fluttering bird’s wings, releasing their sweet fragrances so that every few steps, she was compelled to lean down and smell them.

“How lovely,” said the Carnations as she passed by. “If she didn’t wear farm boots I’d think she was a princess.”

“Yes, indeed,” said the Marigolds. “But how strange that she shuts her eyes when there are so many wonderful colors to look at.”

“Don’t you see how he leads her?” said the Chrysanthemums. “She shuts her eyes because she can’t see.”

The Faun stayed by her side, and together they explored the garden which spread out in her mind like a house with many rooms, so that each time she thought he might turn her around and begin leading her back, they simply kept walking forward. Pride was evident in his voice, and as he took her further and further, her imaginary portrait of him became clearer and clearer. In her mind, he looked back at her with enthusiastic and intelligent eyes, and a poised frame that seemed always ready to sprint forward. Despite her certainty that he was no older than herself, his mannerisms and demeanor felt more mature than boys her own age, and there was nothing untrustworthy behind his steady voice. Whenever she perceived him looking at her, it was only ever with a smile, and try as she might, should could never imagine him wearing another expression.

Near midday, the farm girl asked to be taken back home, and the Faun led her back to where her coat hung from the tree limb. Then the he took her wrist and they left the garden together. In truth, she could easily have navigated her way back home without his help, because although she was blind, the surrounding countryside spread out in her mind like a map, and during their trip to the garden, she had memorized the path. But she preferred his company rather than walking alone, and his warm hand firm on her wrist caused red swirls of light to dance in the darkness behind her eyelids.

When they reached the forest’s edge, the sky hung above them like a grey slate, and the first snowflakes, feathery and wet, began to fall. Across the cornfield, a column of smoke rose from the farmhouse’s red chimney.

“I’ve made a gift for you,” she said, before leaving.

Reaching into her coat pocket, she removed a small paper doll, and handed it to him. The doll had been carefully cut into the silhouette of a girl. A white, paper apron was pasted over her blue farm dress. Pink watercolor splotches brightened her cheeks and in her right arm she held a bouquet of paper roses, painted in bold red blotches. A pair of ink drops served as eyes, placed crookedly on her crinkled face.

“It’s me,” she said after a moment. “Keep it forever. This way, we’ll be together even when we’re apart.”

From her other pocket she removed a second paper doll in the shape of a boy. She had cut a pair of paper legs for him, dressed in brown overalls and black shoes.

“This one is of you,’ she said. “Except I left the face blank because I don’t know what you look like.”

She paused for a moment. When he saw the paper boy, the Faun realized his success in tricking her, and the weight of his lie pressed upon him so heavily he felt, in the same instant, the conflicting urge to shove her away and draw her near to him in a single gesture.

“Let me touch your face so I can see you in my mind,” she said.

He felt suddenly dizzy, as though standing upon the edge of a tall cliff. Even if I let her, he thought, she might still believe I’m a boy. He had eyes like a boy, and a chin, and nose, and cheeks like a boy. But if her fingers went so high as to touch his horns she would know the truth. Nevertheless, he pressed back his fear and leaned his face close to hers.

“Go ahead,” he said. Her fingertips were cool against his skin. She touched his neck, his beard, his cheeks, and his nose. Her dark eyelids moved as though something were beginning to wake beneath them. Higher and higher, her hands crawled up his face like a pair of spiders, and at the critical moment, he nearly turned his face away. But in a sudden movement, her hands leapt across his forehead and touched his horns. And then, as though burnt by fire, she quickly pulled her hands away, clenching them into fists.

“What are those?” she asked.

“My horns,” he said, and paused. “I’m not a boy like you imagine. My legs aren’t like your legs, but the legs of a goat. And instead of feet I have hooves.” Her face became still and smooth and a long silence fell between them. “Now that you know, I’ll not blame you if you stop visiting me,” he said.

She said nothing, but instead reached a hand up to touch his cheek, and felt it wet with his tears. For a moment, her eyes stopped moving behind her lids, and she smiled at him so directly it seemed she could see him completely. “It makes no difference,” said her smile. “I enjoy your visits too much, and promise to see you the next morning and the next. I understand everything and nothing has changed.” That and much more her smile seemed to say to him, and a great relief passed through him.

Afterwards, as he ran back through the forest, his tears left horizontal streaks along his face; his spirit was light and the world seemed completely new. The wind picked up and the creaking branches seemed to say, “She loves you, she loves you!” High in the tree tops, he heard a pair of rooks call down, as if to say, “Good luck! Good luck!” Once more, he was proud of his legs, so proud that when he returned to his garden, he told the roses his mind was set, he would give up his wish in exchange that the farm girl might see.

“Tomorrow I’ll lead her here,” he told the Roses, “and you will fix her eyes.”

And the Roses nodded their heavy blossoms, yes.

But the next day was Christmas Eve, and before dawn the farm girl and her mother drove the wagon to town to sell their wreathes. A large pine tree stood erect in the main square, shimmering with colorful glass ornaments. Along the streets, crowds of people bustled beneath a continuous flurry of snow. All afternoon the farm girl and her mother sold wreathes from the back of their wagon. Those decorated by roses received the most compliments. “Where did you find such red blossoms at this time of year?”their customers asked.

They sold out quickly, and although the farm girl knew her family needed the money, each time a customer left with a wreath decorated by roses, she felt as though she were being robbed of something precious – as though the roses belonged to her and her alone – and fought back a rising sadness that nearly burst from her eyes.

They returned home near dusk, just as the shadows began to lengthen across the snowy landscape, and as the wagon drove up to the farm house, the farm girl turned her face in the direction of the pine forest, and wondered if the boy had waited for her that morning.

Later in the evening, after the farm girl was asleep in bed, her father came home, stomping his feet on the front stoop and sneezing. While his wife and daughter had been in town selling wreathes, he’d been away all afternoon and evening, hunting for tomorrow’s Christmas dinner. In one hand he carried his rifle and in the other he held three dead rabbits by their ears.

“I thought you were hunting deer?” his wife asked at seeing the rabbits.

“I shot one out near the edge of the pine forest,” said the farmer, “but the bullet didn’t take. The animal ran off into the trees. I tried tracking it, but the horse got spooked by the blood.”

The next day was Christmas and the farm girl woke up early to make a gift for the Faun. She cut a new paper doll, this time with horns and goat legs and a daub of brown for a beard. She blew on his face until the paint was completely dry, then put the doll in her coat pocket and left the house. She waited in her usual spot, where the pines met the cornfield, but the boy never came. When she grew impatient she entered the forest and briskly followed the path she’d memorized, arriving at the Faun’s garden within an hour. Waving her cane in wide swathes before her feet, she made her way down the brick path. She shouted many times for the boy, but was met by the thick fragrances and quiet sounds of the garden. Then, all at once, her cane tapped against something hard like a stone, and when she knelt down to touch it, she discovered it was the boy’s hoof.

There he lay on his back beneath the rose bush, shot through the leg. It took her a moment to realize he was dead, because she was unable to see the stillness of his chest or the wound in his leg. She tried to wake him, but he gave no answer nor did he greet her in his usual way, and it was only after touching his cold fist gripping the crumpled paper girl, that she knew. She leaned down and kissed his forehead. White tears fell from her eyes like drops of milk and splashed on his cheeks. Little by little, her blindness faded, and when she opened her eyes she saw him clearly. How handsome he looked to her then, lying as though asleep, as the roses dropped their red petals upon his face.

A high stone wall surrounded the mayor’s garden. Inside, brick paths wound between neatly trimmed hedges, lush plants sprouted from the moist soil, and the soothing sounds of bubbling fountains cast a sleepy tone across the grounds. A rose bush grew at the center of the garden; and all of the roses that grew on the bush were vain and knew that among the many beautiful flowers that took root in the garden, they were the most honored and precious.

“We are tossed on stage after a wonderful performance,” they said. “Men put us in their button holes to look handsome and women’s hearts swoon at the sight of our petals. We are a symbol of love, and love is the greatest virtue.” At hearing this, the daisies closed their petals and the bluebells hung their heads.

Of all the roses that grew on the bush, there bloomed one who was the most vain. Her petals were the deepest red, and her thorns grew long and sharp. Caterpillars never ate holes in her leaves and on bright, clear days, she’d bend slightly her slim, petite stem and gaze down at her reflection in one of the garden’s many pools.

“I am the most beautiful,” she’d say to herself, and all the other roses turned their faces away because they knew she was right.

When the first day of summer arrived, a Bee flew in above the garden. Bright yellow stripes encircled his body and at the sound of his buzzing wings all the flowers looked up towards the sky with anticipation. They opened their petals wide and waved their leaves as he flew overhead. To have a bee land on your petals was a mark of honor, but when the loveliest rose caught sight of the pest, she closed her petals and refused to let the insect in.

“Awful thieves! I won’t have him crawling all over me,” she thought. “My nectar is the most precious in the garden. It’s the sweetest and rarest. Too rare for a bee to steal.”

What the Rose didn’t know was a contest had been announced three days earlier.

Far from the garden, in the northern foothills, stood a large oak tree. In its highest limbs hung a large bee hive with many chambers, at the center of which lived the Queen Bee in a throne room built entirely of shimmering gold wax. She enjoyed nothing more than drinking the honey her soldiers harvested and grew so fat, four servants had to carry her around on a wax pallet in order to move her from one chamber to the next. During her reign as queen, the hive’s only source of pollen came from the wild flowers that grew along the plains, and over time she grew tired of the usual, and often boring taste, desiring something new, something sweeter.

On the first day of summer she summoned her soldiers into her throne room, where they gathered together, shoulder to shoulder before their Queen. Her enormous belly filled nearly half the space when she spoke; all of the bees hushed.

“I’m tired of drinking our honey,” she announced. “The pollen we harvest from the wild flowers is dull and tasteless. My tongue has fallen asleep. So I have decided to hold a contest. Whoever brings me the most delicious nectar and sweetens the hive’s batch of honey, will drink from the cup of royal jelly.”

All the bees trembled and buzzed their wings. Royal jelly was the greatest of all rewards. A single drop was said to double one’s life. Certainly whoever succeeded in bringing back the most precious nectar would go down in history as an honorable soldier.

At once, the bees piled out of the main chamber, and from there, out of the hive and into the world. They all swarmed in different directions. Some north, some east, some west; but none flew south, believing it too cool in the southern villages for the flowers to bloom as beautifully.

One soldier bee thought otherwise.

“Surely the southern plains aren’t completely bare,” he said to himself. “Perhaps the sweetest nectar can be found there. Then I’ll have no competition.” Off he went. He flew for three days, and on the third day, his exhausted wings could hardly keep him aloft. But just before he thought he would drop from the sky, he spotted the mayor’s garden. “Look! An entire jungle of flowers!” he said to himself while flying above the stone wall. “They’re much more colorful than the wild flowers near the hive. I’m sure one of them will satisfy the Queen’s appetite.”

First, he flew down to the marigolds, whose petals looked as orange as pumpkins. But after tasting their nectar, he shook his head, “Your nectar’s not sweet enough.”

Next, he flew to the forget-me-nots whose faces were as blue as a robin’s egg. But their nectar was just the same: sweet, but not sweet enough. Deeper and deeper he traveled into the garden, and each flower he met craned her neck out, fighting for position and calling out, “Me! Here! I’m the sweetest!”

When at last he came to the center of the garden, he discovered the rose bush and the red blossoms were like splashes of blood against the rich green leaves. “These are the most beautiful flowers the garden can offer. Certainly one of them will give me what I need.”

He hovered above the bush and called down to the roses, “Which one of you is the sweetest?” And they all nodded towards the loveliest Rose, whose petals were still tightly closed. He flew down, landed on a nearby leaf, and called up to her.

“You are much prettier than the wild flowers that grow near the hive. Even with your petals tightly closed I can tell you must be the most beautiful flower in all the world. I’ve traveled three days in search of the sweetest nectar. My queen demands it. The soldier who returns to her with the prize will be awarded a cup of royal jelly. It would be a great honor and my name will go down in history. I know I’m a simple soldier bee, but will you open your petals so I can taste your nectar?”

“I’ve hardly listened a word you’ve said,” replied the Rose, and flexed her stem, causing her thorns to glisten.

“Ah,” said the Bee. “You have stingers just like me. Although I only have one. Every soldier is born with one stinger. It’s sharp and meant to protect the Queen from danger; but we can only sting once. Then we die.”

“I can sting as many times as I like and never die,” said the Rose, straightening herself. “My thorns protect me from the gardener’s shears. If he ever tries to clip my stem I’ll prick his fingers.”

“You’re very beautiful, and very proud,” said the Bee.

“Of course,” she said, “which is why you can’t have my nectar.”

“Just a few drops to take back it to my hive,” said the Bee. “Our honey will be sweetened and the Queen will be pleased. She’ll ask for more, and I’ll lead an entire swarm to visit this garden and all the soldier bees will worship you.”

“Worship me?” she asked.

“You’ll be queen of the garden,” said the Bee. “It’s a shame you’re hidden behind stone walls. No one can see you. Flowers like you are destined for great things.”

It was what she had always thought; even in her earliest days as a tiny green bud, while the rest of her sister-roses were discovering the world with eager curiosity, she felt trapped, constantly scowling at the garden’s stone walls for imprisoning her. I’m meant for something bigger, she often thought to herself, something profound.

“If you’re sincere,” said the Rose, “then you may have a taste; but only a small bit.” The Bee watched from the nearby leaf as she opened her blossom to reveal to him her true size. One by one her petals unfolded and when she was finished, she loomed above him like a blazing red sun. He was about to fly up and drink when a sudden noise startled him. The garden’s wooden gate banged opened and the gardener appeared, walking swiftly down the brick path with long strides. All of the flowers began to whisper, “Hide yourselves! He’s coming!” making themselves as small as they could, hiding their blossoms behind leaves or ducking down beneath a patch of shade. The roses all closed their petals and flexed their thorns, but the loveliest Rose did nothing to hide herself.

“Let him try and clip me,” she said. “I’ll scratch him!”

“What does he want?” asked the Bee, and one of the roses answered him with a quick whisper.

“Of all the flowers in the garden, the mayor’s wife prefers roses. She puts them in a blue vase on her writing desk. She feeds them water and the window gives plenty of light, but no flower wants that fate. To be clipped is a life cut short.”

Above the hedges and bushes, the Bee caught sight of the gardener approaching. In one hand he carried a sheet of newspaper. In the other, his pruning sheers – the silver blade curved like the beak of a bird.

“Hide yourself,” said the Bee, but the loveliest Rose ignored him, seeming to fan her petals even wider.

He wound his way along the path and walked right up to the rose bush, scanning the blossoms with quick, darting eyes. His mind was elsewhere; there was still hedge trimming to do in the front lawns and rain was predicted before dinnertime so he hardly took notice of the loveliest Rose and instead, grabbed for the nearest stems. The Bee listened to the shnickt-shnickt of the sheers. When a rose was clipped, her tiny voice was pinched high. The gardener laid them side-by-side on the sheet of newspaper until he had a small bouquet. When he finished, he rolled the paper round their stems and jogged back down the path. When they heard the gate bang shut, the entire garden relaxed and the flowers came out of hiding.

“See,” said the Rose. “He knows to leave me alone. My thorns are sharp.”

“That’s not true,” said the Bee, and his voice was low. “Men have stolen honey from my hive. They take what they want. Our soldiers try to fight them off, stinging and stinging, until dead soldiers cover the ground, but the men keep coming. They’re strong. You’re careless with your beauty. How terrible it would be if the gardener clips you. The garden will lose its queen, and the world its most beautiful flower.”

None of the flowers ever paid her compliments, and although her petals were already deep red, she blushed an even deeper shade at hearing the bee’s kind words. The sky began to darken, and above the mansion’s rooftop, thunder clouds towered. Rain began to fall and the flowers craned their faces up to drink.

“Take shelter in my blossom,” said the Rose. The Bee did as he was told, flew up and nestled deep inside her petals, which folded above and around him forming a small, comfortable red room. The storm took many hours to pass, and by the time it finished the fountains had overflowed, the garden beds were soft and muddy, and the bee lay sound asleep inside the Rose. When night came, a cool, transparent mist hung in the air and the Rose, feeling the delicate weight of the Bee nestled in her blossom, was overcome by a sudden realization; that despite her sister-roses that grew alongside her, and despite the hundreds of other flowers in the garden, she was incredibly alone.

Across the sky, stars appeared, and although she’d stared up at them countless times before, tonight they seemed infinitely far away. As she gazed and dreamed, her mind flitted about unexpectedly, and she imagined herself growing taller and taller, sprouting like an enormous tree, until she was so high above the clouds that the wide open countryside spread out beneath her and her petals touched the sky itself. The Bee, still asleep, shivered inside and she was momentarily jolted from her fantasy. How lucky he is to have a pair of wings, she thought, and although she knew it impossible, she wished he might invite her to fly with him over the garden wall and out into the vast world beyond.

For three days, the Rose kept him wrapped inside her petals. The other roses poked fun at her for loving a bee. Nothing was more ridiculous than seeing their sister, “swooning over a pest whose only purpose is to rob from our petals.” But she paid them no attention and concentrated on the Bee’s heartbeat that pulsed inside her.

On the third day, he woke and stirred. The Rose opened her petals and out he flew.

“Are you leaving this afternoon?” she asked. “You’ve been asleep for three days.”

“I must have needed the rest after so long a journey. But I should be going back to the hive,” said the Bee, and although he had only spent a waking-day in the garden, a large part of him wished to stay forever. There was no other place as beautiful; the old oak tree, the hive, his soldier friends and the Queen all paled next to the Rose and her garden; but he was a soldier, and duty bound him to complete his mission.

“May I take some nectar?” asked the Bee.

“Only if you keep your promise to come back,” said the Rose.

“I promise,” said the Bee, and with that, he flew up and dipped his head deep inside her petals. He swallowed mouthfuls of nectar until he was drunk on the sweetness, and when he lifted his head to take a breath he said, “Ah! I’ve never tasted anything so magnificent!”

When he was finished, he hovered above her in a delirious state, wished her goodbye, and flew off back to the hive. She waved her petals after him and watched him go until he was hardly a speck against the sky.

At that very moment, in one of the mansion’s third floor rooms, the mayor’s wife sat at her desk in front of a small window overlooking the garden. She had just finished writing letters to friends and relatives, inviting them to her daughter’s seventeenth birthday celebration. She licked the envelopes, sealed them shut, and stamped each. Then she rang a small bell, and a servant appeared who took the letters to post. At the corner of her desk sat the blue vase, half full of water, displaying the bouquet of roses the gardener clipped.

In three days, the Bee returned to the hive and presented the Rose’s nectar to the Queen. Upon tasting the batch, her wings buzzed and her antenna twirled with excitement. “It has awakened my tongue from a very deep sleep,” she said.

At once, the Bee was proclaimed a hero. He drank from the cup of royal jelly and the Queen promoted him to Captain and put him in charge of a troop of bees assigned to return to the mayor’s garden and bring back more nectar.

Back at the mansion, the mayor’s wife put all her servants to work preparing for the birthday party. When she shouted orders everyone scurried about like insects. All of the festivities were to take place in the garden and the loveliest Rose watched the servants hang lanterns from tree limbs and erect brightly colored tents. This bustle and activity wasn’t enough to distract her, and she turned toward the sky, watching for the Bee’s return.

As soon as possible, the Bee and his troop began their journey south. Few of them had ever flown so far and so long, but he kept them going at a steady pace all day and all night. With each passing hour he grew more and more anxious, his eyes fixed on the horizon in anticipation of catching first sight of the dark speck that was the mayor’s mansion.

When the day of the birthday party arrived, crowds of guests filled the garden. A band played music, glowing lanterns hung from trees, candles burned beneath the tents, and servants shuffled back and forth carrying platters of steaming lamb and frosted pastries, glasses of bubbling champagne and small skewered sausages. A large table of gifts wrapped in glittering paper twinkled nearby and the mayor’s wife still barked orders while her husband lounged beneath one of the tents, smoking his pipe. As for their daughter, a warm blush burned in her cheeks and her dark curls flowed down over her bare shoulders. She was constantly surrounded by a group of handsome, respectable young men, each vying with one another in a desire to distinguish themselves and win her attention.

At dusk, on the third day, the Bee spotted the mayor’s garden. From high up, the lanterns and flickering candlelight made the garden appear on fire. He led his soldiers down towards the center of the garden, where they swarmed in, unnoticed by anyone.

“You’re back!” said the Rose, and the nearby lantern light, which cast a magical glow across the entire garden, caused her fluttering petals to appear like a whirling pinwheel. “I’ve been watching the sky ever since you left.”

The Bee, weak at the sight of her, landed on a nearby leaf, the same leaf he’d first viewed her from, and although only a week had passed, he was eager to tell her everything that had happened since he’d said goodbye. “This is the Queen of the Garden,” he said, turning to his troop, “The loveliest flower in the world.” All the soldiers flattened their wings, lowered their heads, and bowed to the Rose, whose petals blushed redder; and it was in this moment that the Bee decided he’d never return to the hive. His fellow soldiers were quite capable of flying back on their own, and together, would be able to carry more than enough nectar. Yes, it was settled; the garden was his home now and the Rose his new Queen.

At that same moment, the young gardener, leaning against a hemlock tree, watched the mayor’s daughter flirt with a group of young men who surrounded her. He loved her from afar, and had done so ever since he’d been hired a year ago. His small earnings afforded him nothing to give to her as a birthday gift and the sight of her accepting the young men’s presents – her large eyes gazing up at them in anticipation, their lips kissing the back of her hand, her careless laughter – made him furious. He balled his fists and decided to find something precious to give her, something to show that he loved her; removing his sheers from his pocket, he crossed the garden, shoving past servants and party guests, and marched directly to the rose bush.

The Bee, beneath the Rose’s red shadow, was in the middle of recounting his promotion to Captain when the gardener suddenly loomed like a dark cloud above the bush. The soldier bees instinctively scattered to the air and the rest of the roses – catching sight of the sheers and realizing what was about to happen – shouted at their sister to hide; but it was too late. Already, the gardener was reaching down and in a single gesture, clipped the Rose’s stem – schnickt! She let out a pinched gasp and fell sideways into the gardener’s palm; grasping her gently, he lifted her up to his face, pushed his nose inside her blossom and inhaled deeply.

Everything happened so quickly; the Bee hardly knew what he was seeing. Go! Go! Go! his mind seemed to shout, and his wings buzzed to life carrying him swiftly up to the Rose.

The lush redness that had once smoldered in her like a hot coal, dimmed and all her petals shivered. She was unaware that she’d been cut, and in her confusion asked the Bee, “Is it winter already?”

He clung fervently to her blossom, his antennae touching her all over like small kisses. A drowsiness descend upon her and she felt something deep and restful tug at her senses.

“I have to sleep now,” she said. “Stay in the garden and you can hide in my blossom again… to keep from getting cold.”

The Bee nodded yes and she felt absolute happiness in knowing that he – like the sky and the sun – would be there when she woke. The last threads of life left her and before dying she gave a faint sigh and the sweet nectar she’d been storing for him poured from her blossom like tears.

Something snapped inside the Bee; he flew up, quick as a dart, landed on the gardener’s neck and plunged his stinger deep beneath the skin.

The gardener winced in pain, swatting at the spot. Upon drawing his hand away he looked down to discover a bee, curled up in his palm. “Pest,” he said, and flicked the insect away, giving it an angry look. The Bee landed in the nearby garden pool – the same pool where the Rose often gazed at her reflection – and floated dead upon the surface.

With a pounding heart the gardener followed the brick path to one of the part tents where the mayor’s daughter stood, illuminated by the diffused light of the lanterns. He pushed his way through the crowd of young men that surrounded her and held out the rose. She smiled at him and blushed – but whether it was out of embarrassment or passion, the gardener could not tell. An awkwardness hung in the air as the young suitors surrounding her stared at the scene, looking the gardener up and down with contempt and whispering to one another with sneering grins. One of them, a handsome young man with smooth cheeks and an aggressive stare, removed the boutonnière from his lapel and handed the pin to the gardener.

“Here friend,” he said. “Pin it to her.”

The mayor’s daughter thrust her chest forward, inviting the gardener to pin the rose to her; he did so, and the men delighted in noticing the slight tremor in his fingers.

“It’s lovely,” she said when he’d finished, but she spoke to him as though he were a child and the gardener perceived her disinterest. She’s only being polite, he thought, and the men slowly closed in around her, forming a circle and cutting her off from his view. Their conversation picked up from where it had left off, as though the gardener had been simply a dream, a figment of their collective imaginations. He stood there a moment longer, defeated – then briskly turned and left the tent, rubbing the bump on his neck where the bee had stung him.

By midnight, all the stars appeared closer and brighter and the party seemed to have risen a little toward the sky. The mayor’s daughter, possessed by a dizzying happiness, danced until her feet burned. And after each song, whenever one of her partners kissed her hand or complimented her beauty, she felt as though she were the center of everything, and nervously touched the rose to make sure it was still pinned above her heart.

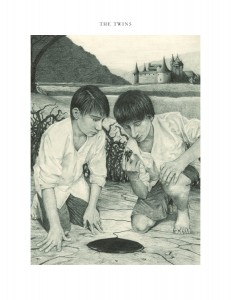

THE TWINS

For fifty-three days not a single drop of rain fell and a burning drought ravaged the land. Crops withered in the fields and deep cracks split the soil. Wildfires swept across the plains and the sky turned black with smoke. People driven mad by thirst waded out to sea and swam towards the horizon, never to be seen again; while in the surrounding villages, dead livestock littered fields and farmyards, and mothers bore no milk to feed their newborns. A rising anxiety swept across the country, and the King, fearful of a revolt, held counsel with his ambassadors. The Bishop, who served as head of the counsel, advised the King, saying, “You must find someone to bear the blame for all this misfortune. Otherwise, you’ll lose your crown.” And he reminded the King of a witch woman who lived in the lagoon.

“Arrest her for treason,” said the Bishop. “Your citizens will see her execution as a powerful move and honor you as their protector.”

“And if the drought continues after she is executed?” asked the King, but the Bishop merely waved his hand, as if to suggest this notion out of the question and unreasonable.

The Queen seconded the counsel’s plan. “Think of your sons,” she said to her husband. “If you lose the throne, their future will be in jeopardy.” This alone was enough to sway the King’s decision, because in all the world, he loved no one more than his twin boys.

So, that same day he dispatched a group of soldiers, led by his Chief Lieutenant, with orders to travel to the sea, arrest the witch, and bring her back to the castle. The troop galloped west until they arrived at the beach. In order to reach the lagoon, they were forced to dismount, leaving their horses behind because of the shoreline’s uneven terrain, covered in black boulders as far as the eye could see. They made their way slowly by foot, holding rank, careful not to twist an ankle between the rocks or fall forward upon the jagged stone. As the evening light ebbed, their march slowed and the ground beneath their feet became more and more difficult to see. Dark shapes, flitting here and there among the nearby shadows, paralyzed some of the more superstitious men, who feared that each step closer to the witch’s cave meant their doom.

“Look! It’s her,” whispered one soldier to another, pointing to his right where a pair of flashing green eyes peered out from the shadowy rocks.

“No,” said the other soldier, “it’s only a cat. See?” The second soldier, stepping out from the advancing line of troops, reached down among the boulders only to pull up a mangy black cat by the scruff of its neck. The animal glared at both men with large yellow eyes. “See,” he said. “They live all over the beach.”

“Cats!” said the first soldier, who now laughed at having acted the coward, but as he pressed forward with the rest of the men, it seemed as though his eyes were suddenly able to penetrate the surrounding shadows more deeply, catching sight of the wild animals lounging on distant boulders; one, then another, and still another, until he realized the darkness was alive and moving – that hundreds of cats infested the beach.

The Lieutenant ordered torches to be lit and the line of men continued the rest of their journey to the far end of the lagoon surrounded by orange firelight.

The witch lived in a dome shaped hut built from dry grass and sticks lashed together with leafstalks. A pale yellow light glowed from within, throwing strange shadows across the sand. Out front, an iron pot, filled with a bubbling liquid, hung above a crackling fire. A dull knife lay in the sand next to three gutted fish. The soldiers formed rank a few yards away from the hut. When the Lieutenant shouted for the witch to come out, the light inside the hut blew out and the torn black curtain, which hung across the doorway, drew aside.

All the soldiers were paralyzed by her beauty. Black braids of hair sat coiled upon her head like fisherman’s rope. Her bare feet looked like a pair of white fish peeking out from the hem of her thin, transparent dress. Her naked arms floated at her sides like a pair of green snakes and her eyes, pink as coral, were dazzling and luminous, as though two candles burned behind them. None of the soldiers dared move any closer, fearful she might enchant them but their Lieutenant, dressed in his blue uniform, gold epaulets faintly glinting in the torch light, stood untouched by her spell.

Stepping forward from the group, he unrolled a sheet of parchment and read in a commanding voice the King’s orders, explaining the crimes and punishment set against her. “How do you plead?” he asked.

The witch raised her chin and said, “I can turn moonlight into milk, sand into sugar, but the drought has come by itself.”

The Lieutenant, deaf to the truth, bound her wrists with rope. She put up no resistance, but shortly after leaving the cave, while stumbling back across the boulders, the men’s torches suddenly extinguished.

“I can’t see!” one of them shouted and a shudder passed through the group, as though sensing some evil thing watching them. Some fumbled to draw their swords while others raised their hands in front of them like blind men, bracing for what might come next.

From the surrounding shadows a terrible shrieking chorus sounded – and before the men knew what was happening the cats were upon them, leaping up to bite and scratch their faces.

“Kill them!” the Lieutenant shouted amidst the chaos, but the men had already begun to tear the hissing animals off their bodies, beating them against the rocks and hurling them out into the rough, crashing surf.

The witch did not try to escape.

The execution took place in the royal courtyard three days later. At the center stood the executioner’s platform surrounded by a large crowd of onlookers. High up, the King and Queen watched from a canopied balcony protected from the blazing August sun. The crowd cooled themselves with paper fans and from the King’s perch, the constant fanning appeared like flapping dove’s wings.

Shortly after noon, a caged wagon drawn by a donkey, wheeled out into the courtyard. Locked inside the cage lay the witch. Two guardsmen led the donkey by the bit, but after a few paces forward, the animal stopped moving, and no matter how hard the men tugged the reins, the beast remained stubborn and unmoving. So they unlocked the cage and pulled the witch out of the wagon by her wrists. She let out a soft groan as they lifted her under the arms and carried her towards the executioner’s platform.

Three days of imprisonment in the castle left her thin and wasted and her feet dragged in the dirt. Her head had been shaved that morning, but surprisingly, without hair, her beauty seemed strangely enhanced, and those in the crowd who fervently supported the execution, now felt a tug of pity at seeing doom’s shadow darken such a lovely, youthful face. Everyone had expected a vile, ugly woman, and a silence fell across the courtyard so profound that those spectators who had been ready to spit and swear at the witch were too ashamed to look as the guards marched her past.

They carried her up the platform, her ankles banging against each step. But before they laid her on the chopping block, the King allowed her to speak.

Raising her head, she stared up towards the balcony, locked her clear, pink eyes upon him, and said, “Before the sun sets, that which you love most will be taken from you.”

As she spoke, her expression contorted into a frightening snarl and her lips pulled back to reveal her pearl white teeth. When she had finished, a murmur hummed through the crowd, and many onlookers turned their faces up towards the balcony. The Queen gripped the railing to keep from fainting, then sat back in her throne; but the King stood firm at hearing the witch’s curse, his face an unflinching mask, and after a pause, extended his right arm over the edge and dropped a red silk handkerchief, signaling the executioner.

The guardsmen pushed down on the witch’s shoulders and forced her to kneel. Then, while one pressed her head upon the chopping block, the other tied her arms behind her back with heavy rope. The executioner approached her from behind, and many in the audience covered their eyes with their fans.

Down came the axe – the blade’s thwack echoed off the courtyard walls and the witch’s head dropped into the basket. From the severed neck, a fount of blood flowed, like from a bottle, pouring down the chopping block and off the edge of the executioner’s platform where it ran in a straight line along the dusty ground. The crowd quickly parted, tripping over one another in a rush to lift their feet, while from the balcony the King and Queen watched the blood move like a bead of water running down glass.

“Stomp it out!” he shouted, but no one listened.

The blood traveled through the crowd and outside the castle walls, rushing over stones and around trees. It passed over a small footbridge and wound through the dried-up vineyard where the King’s twin princes were playing.

The Queen had forbidden their presence at the execution, ordering their teacher to give them poetry lessons beneath the old mulberry tree far out on the castle’s private grounds. But the lethargic old schoolmaster had fallen asleep in the sweltering heat with the poetry book lying face down on his chest while the twins, left alone to their own mischief, went exploring the nearby vineyard. When the trickle of blood found them it stopped and pooled at their feet.

“Look,” said Peter, crouching down. “Wine!”

“But the drought has killed all the grapes,” said Nathaniel. “How can there be wine?”

“We’re both princes of this land,” said Peter. “The garden has saved some for us as a sign of honor.”

They were twelve years old and at first glance, indistinguishable from each other. But Peter was wilder than his brother, his fingernails packed with dirt, his hair uncombed and his eyes bold and challenging to whomever they fell upon. Nathaniel, on the other hand, inherited his mother’s attention to manners and walked with straight posture and a permanent frown. Although he felt most comfortable within the quiet walls of the castle, he followed Peter everywhere and often regarded him not as his twin, but as an older, more experienced sibling, with whom he secretly wished he could trade places.

“I’ll have nothing to do with it,” said Nathaniel. “It’s black and probably poisonous.”

“You’re a coward,” said Peter, “It’s been so long since I’ve had wine I can hardly remember the taste,” and he dipped two fingers into the blood, brought it to his mouth and licked his fingertips.

The instant the blood touched his tongue, he slipped into a deep sleep and fell backwards into a tangle of dried grapevines. Nathaniel, tried to wake him by shaking his shoulder but the spell was so powerful Peter hardly breathed and his heart slowed to an almost inaudible thump-thump. Run! Run! the voice in his head shouted, and Nathaniel, quick as a hare, darted back through the vineyard towards the castle, shouting for his mother.

Meanwhile, the entire crowd of spectators, led by the King and Queen, followed the trail of blood out past the castle walls. When they came to the footbridge, they met Nathaniel. Tears ran down his cheeks, a wild terror flashed in his eyes, and upon seeing his mother he ran to her and buried his face against her robe. He led them back toward where his brother lay but when they reached the mulberry tree, where the twin’s teacher still lay sleeping, the Queen caught sight of her son’s body lying in the distant grapevines. A pin stuck her heart. “Peter!” she shouted, and broke free from the crowd, her long, elegant sleeves billowing behind her as she ran.

But the witch’s curse was black and vengeful, and each step the Queen took towards her son added a year to her life. In a flash, her hair went from brown to white. Her smooth forehead and cheeks sagged with wrinkles and her joints stiffened. A hump grew on her back beneath her robe and her teeth fell from her gums. She collapsed between the grapevines, no more than fifty paces from Peter, her delicate crown rolling along its edge across the dirt like a coin.

Five men in the crowd held back the King, whose legs thrashed to free themselves and run to his wife and son. When he finally calmed himself, the Bishop and a few counsel members escorted him back to the castle and helped lay him in bed.

The next morning, thirty yellow canaries were released from cages and sent flying across the vineyard only to drop dead at a certain distance from the prince. In this way, the curse’s boundary was discovered and staked out: a perfect circle two hundred paces in diameter with Peter lying at its center.

The King stationed guards day and night around this perimeter and gave strict command that no one be allowed past without his permission. He ordered a canvas tent to be set up at the boundary, where he took all his meals, sitting in a chair beneath the shade and peering through a telescope in order to clearly see his wife and son. He lingered on Peter, who he knew was alive from the slow and rhythmic inhale and exhale of the boy’s chest. For hours, the King would stare through the telescope without removing it from his eye, as though his own life hung suspended between his son’s every breath.

Under his father’s orders, Nathaniel remained in the castle. Each day passed like the one before and he missed his mother and especially Peter. The twins shared a bedroom, and Nathaniel couldn’t escape the silence of Peter’s absence. His empty bed, his limp shirts hanging in the wardrobe, his fingerprints smudged on the window pane continually reminded Nathaniel of his missing brother. The Bishop, at seeing the boy’s distress, gave Nathaniel a rosary.

“Pray on this,” he said, “and the angels will watch over him.” This he did every evening before bed, silently praying while rubbing the beads between finger and thumb.

Most nights his restless mind kept him awake and he’d sit at his bedroom window gazing down upon the vineyard where the guards standing duty held bright, burning torches. From his vantage point high in the castle Nathaniel could easily make out the flickering circle and knew that somewhere at the center of the fiery ring lay his brother. Peering through the glass, he often caught his own ghostlike reflection looking back at him. He spoke to it as though it were his brother, until his eyes became drowsy and he fell asleep, curled up on the sill with his head against the pane.

Three weeks passed.

The King decreed any person capable of rescuing his son would be rewarded half the royal vault and a high ranking seat among his counselors. Word spread quickly throughout the neighboring provinces and within three days, a man, traveling by foot, arrived from the south, followed by a young aide bearing a red, fluttering banner. After being received at the castle gate, a guard escorted the man and his aide to the vineyard where the King greeted them from beneath his tent. At first glance, the King was certain of the man’s capability in saving his son. He moved with a graceful confidence, as though every gesture had been carefully planned beforehand and carried himself with an air of such nobility, the King had to suppress the urge to bow before him. With his chin tilted slightly upwards and his spine straight and rigid, his head appeared like a giant egg balancing atop his neck; while at the same time his lean frame seemed rooted to the hard ground, as though no force in the world could ever knock him down. Across his shoulders draped a waist-length cape sewn all over with robin’s feathers, and his hair, combed back from his temples and forehead, appeared to have been blown by a strong and constant wind.

“Dear King,” said the man, “I’ve come to accept your offer and rescue your son. I’m the fastest man alive and no curse can touch me.”

An array of flashing gold medals hanging round his neck served as proof of his athletic achievements, and as the King eyed him from head to toe, he was further convinced of the Fastest Man’s abilities by his sinewy thighs and his calf muscles bulging beneath his red tights.

“Save him and my kingdom will be yours,” said the King, and the thought of holding his son, perhaps in as little as a few moments, caused a rim of tears to rise in his eyes.

The Bishop, who stood nearby, took a small medallion from his pocket, offering to pin it onto the Fastest Man’s cape. “It’s Saint Michael the Archangel,” said the Bishop. “He will protect you.”

“No,” said the Fastest Man, swatting at the Bishop’s hand. “The slightest bit of extra weight will slow me down. I must go unburdened.”

With that, the Fastest Man turned to his young aide and bowed forward in order for the boy to remove his medals. After lifting each one off his master’s flexed neck, the boy slid them onto his forearm where they dangled freely, tinkling like chimes in the quiet afternoon air.

The circle of soldier’s parted and the King watched anxiously as the Fastest Man squatted down in a runner’s pose. He took three breaths, leapt from the ground like a rocket, and sprang forward with such speed his feet kicked up a trail of dust. The King stood from his chair to get a better look at the Fastest Man, now a red blur, dashing ahead with arms pumping, feet sprinting through the dried grapevine as though they’d run this same path a hundred times before; but no sooner did the King realize that yes! he’d see his boy delivered to his arms than the curse gripped the Fastest Man. Although his feet avoided tripping and he kept up his impressive pace, he’d hardly gone half the distance when his lean, muscular frame shriveled thin as a skeleton. With a sudden jerk of his neck, as though being yanked by a leash, he plunged forward with a violent momentum, tumbling head first, falling to the ground amidst a cloud of dust, his feathered cape fluttering down like a broken flag.

“How close did he get?” asked the Bishop, bowing his head and making the sign of the cross.

“Forty paces,” said the King, overcome by such disappointment his trembling lips could hardly form the words.

Later that afternoon, the King wrote a letter of sympathy, explaining the circumstances witnessed that morning. The letter was sent along with the young aide who, wearing the medals around his neck, returned to his countrymen bearing the sad news of their great champion’s death.

The second man arrived from the west two days later. From their lookout posts on the castle’s highest towers, the guards on duty spied him coming over a mile away, his suit of bright silver armor flickering like an approaching star. He rode up to the castle gates on a white Palomino, where he was received and escorted to the King’s tent. Unlike the Fastest Man, whose elegance and grace was apparent at first glance, this newcomer was a knight of the highest order unlike any the King had ever seen and who appeared more machine than anything else.

Everything about him was hard and rigid and heavy, except for the white cape, which lay draped like a wedding train across the hind quarters of the Palomino. It was only when he dismounted and lifted the visor of his helmet to reveal a pair of hooded brown eyes, wide pink nose, and fully grown moustache the King was able to recognize a man lay hidden somewhere beneath the intricate plates of metal.

“My dear King,” said the Knight. “News of your troubles reaches far and wide. I’ve come to rescue your son. My armor is blessed by his eminence, the Archbishop; swords shatter against my breastplate and even the keenest archer cannot pierce me with his arrows. And here,” he said, lifting his shield, on which was engraved an ornate cross, “my shield bears the emblem of the Church. When raised in defense, it’s as though God himself has opened his hand before me, protecting me against harm.”

The King nodded. “And your horse?” he asked. “Is she protected?”

“Her bridle is woven with hazel and her coat has been sprinkled with salt. Brass shoes are nailed to each hoof; she is keen and quick. Trust in me and I promise she’ll carry me to your boy.”

“If you perform as courageously as your words suggest, my kingdom will be yours,” said the King.

The Knight swung himself back into the saddle, flipped down his visor, and reined his horse around to face the distant, sleeping prince. The circle of soldiers parted wide enough for the Knight and his steed to pass through. “Gid’yup!” he shouted, dug his spurs deep into her hide and whipped her flanks. Her hooves thundered against the dried earth and the King felt their vibrations rise up through the legs of his chair.

The Knight, his white cape outstretched behind him, his armor like so many mirrors reflecting the sun, seemed as though he’d galloped out of a dream, and the King, lost in this moment, was awestruck and dazed. Go! Go! shouted the voice in his head, and although a warm heat pulsed urgently in his brain, the entire scene unfolded before him slowly, as though each minute passed like an hour.

But the curse cared little for all the Knight’s preparations, and no amount of salt or blessings could protect him from his fate. The Palomino’s clopping hoof beats suddenly faltered, her beautiful mane changed from white to grey and her taught muscles loosened and turned to fat. Fearful of what was happening to her, she snorted, whinnied, and reared up. But by now she was already a much older horse, and the weight of her master, who struggled to keep himself in the saddle, caused her hind legs to completely give out, and like a toppling tree she fell backwards, crushing the Knight beneath her. The glorious image that had, only moments ago, galloped forth, now disappeared from sight, and the King, trying to pierce the thick cloud of dust kicked up by the fall, held his breath to see what might happen next.

The horse, terrified and dying, tried desperately to raise herself, and as she did, the Knight managed to roll out from under her. He stood up. His cape, hanging from his shoulders by a few torn threads, blew loosely as a warm breeze swept across the vineyard; but his armor, despite the fall, still shone brilliantly beneath the sweltering sun. Before making his way to the prince, he hobbled to his horse, who by now had stopped screeching and lay exhausted and panting on the ground. He knelt down and petted her for what seemed many minutes, then stood and began making his way once more towards the prince. The King, transfixed by the scene playing out before him, stood up from his chair to get a better look.

The Knight raised his shield before him and advanced cautiously, as though expecting a sudden attack from an invisible enemy. After only a few steps forward the shield’s weight quivered in his aging arm and he dropped the mighty disc, where it clanged to the ground and wobbled back and forth like an empty bowl. After a few more stumbling steps forward, he turned around as though to make his way back, but immediately fell to the gravel and did not rise again.

“How close did he get?” asked the Bishop.

“Fifty paces,” said the King lowering his telescope, and the Bishop bowed his head and made the sign of the cross.

The third man arrived from the east a week later. He was received at the castle gates and escorted to the King’s tent, making a low and gracious bow. His brown skin glistened wetly, as though covered in grease, and on his head he wore a dazzling, white turban. When he unwrapped the cloth, there, hidden beneath and resting on his bald scalp, stood a small bottle of liquid.

“This,” he told the King, “is precious oil from the moon. When rubbed on my body I’m immune to death. I’ve survived snake bites and fatal wounds that no man could survive.” He lifted his shirt to reveal a variety of scars mapped across his chest, then rolled up his sleeves to show off even more markings etched into his forearms and wrists. The King, repulsed by the sight, felt the urge to look away.

Although the Knight had his own set of charms and protections, this newcomer seemed far more mystical. His magic, although strange in its own rite, seemed rooted to some ancient secret; and although the Bishop looked down his nose and sneered at the Oil Man, the King was too desperate to scoff at such oddities.

“Save my son and I’ll be forever in your debt,” said the King.

The Oil Man uncorked the bottle and rubbed himself all over until his skin gleamed like a porcelain figurine. The circle of soldiers parted and he walked past them with a purposeful and fearless confidence. He moved as though underwater and every gesture felt as though he were detached from the Earth, as though gravity ignored him, or simply couldn’t touch him. The King stood to watch as he marched forward in a straight line, never veering from his path, stopping now and then to splash more oil over his arms and cheeks.

“Perhaps it will work,” said the Bishop, laughing.

But the Oil Man turned out like all the rest. He fell near the dead horse, flopping forward like a sack. His beautiful turban unraveled and in the fall the precious glass bottle went flying, shattering upon the ground where the oil spilled and soaked into the dust.

“How close did he get?” asked the Bishop.

“Not close enough,” said the King.

Another month passed and so many people attempted to save the prince that soon the vineyard was strewn with corpses. The sun beat down upon the castle grounds, and Peter’s skin, exposed to the harsh rays for so long, burned red and his parched lips cracked and blistered. Vultures circled overhead and the deathly stink rising up into the sweltering sky seemed to grow more and more potent, adding to the King’s sense of misery. Beneath his father’s overbearing protection, Nathaniel remained in the castle. One night, the King called him to his bedside. With tears in his eyes, he took Nathaniel’s face between his hands and stared at him for a long time, seeing both Peter and his dead wife reflected in the boy’s features.

“You’re all I have left,” he said.

“Send me, father,” said Nathaniel. “I’m young. I can reach Peter.”

“No,” said the King, lying back on his pillow, and his voice was stern now. “I can’t bear to lose you both.”

But Nathaniel missed Peter too much, and that night, he slipped out of his room and crossed the castle grounds, making his way towards the vineyard. As usual, the soldiers were on duty, but weeks of fatigue had dulled the men’s senses, making it difficult to fight off the comforts of sleep. Nathaniel found two guards dozing and slipped between them without detection.

It was quite dark, so he aimed himself towards the center of the circle as best he could guess and began walking in a straight path. He hadn’t considered the darkness. If he veered off course he’d never make it. “And even if I do, what will happen when I get there?” he thought, “I imagine by the time I reach him I’ll be a man. Large enough and strong enough to carry him. And if each step towards Peter makes me older, then each step back towards the castle will make me younger. Think how happy father will be when he sees us tomorrow.”

He inhaled deeply and stepped into the circle. The instant his foot touched the dry ground, a tingling current passed through all his limbs. His spine stretched like taffy and he felt his body expand, as though the wind had suddenly rushed down his throat and filled his insides with air. Every few steps forward added an inch to his height, so that after seven steps, he was already a young man. The sudden increase in height split his clothes at the seams and his boot laces snapped at the sudden widening of his feet. Hair sprouted from his chin and beneath his nose a faint moustache grew. All the while a lean musculature bulged across his arms and shoulders and his twelve year old mind thrilled at the change taking place.

Pausing to look at his hands beneath the moonlight, he hardly believed the large, thick palms and wide thumbs were a part of his own body. But the sudden bloom of youth was fleeting and at age thirty-three he came across the corpse of the Oil Man, whose eyeless, rotting face had been nearly pecked clean by birds.

The sight was too awful and he quickly looked away, cupping his hand over his mouth and nose to cover the choking smell. But the stench only grew more nauseating as he passed corpse after corpse, batting away swarms of flies buzzing near his ears.

At age fifty-four, he found his dead mother lying on her side. As he hurried past her body, the voice in his head seemed to shout, Don’t look! but he couldn’t stop his eyes from glancing down at her. To his relief, her face was turned away, and the back of her head, covered in white hair, appeared so different compared to the memory of his living mother that the corpse seemed like a stranger to him.

Further along, he came upon the Knight, whose suit of armor, now dulled and overgrown with thorny weeds, appeared like a great heap of empty metal. Nearby, covered by the matted red cape of robin’s feathers, lay the body of the Fastest Man, so sunken and decayed he appeared to be slowly sinking into the earth.

At age sixty, he felt the pull of gravity on his body, and it seemed to steadily increase as he continued along, as though his pockets were slowly filling with stones. Everything became heavy and a haze drew itself across his eyes, causing the now distant torches of the surrounding soldiers to grow fuzzy and spread out like expanding star bursts. At seventy-four, he lost two teeth, spitting them into the dark. His stiff beard swung down to his waist and his clothes, torn and ragged from his body’s rapid expanding and shrinking, now hung from his thin, feeble frame. At age eighty-eight, with a bald scalp, trembling knees, and ever dimming eyesight, he spotted Peter lying in the vines. Five more steps and he stood above him. He was ninety-three years old and knelt down at his brother’s side.

A wide, nearly toothless smile broke across his face at seeing Peter, and he leaned in and kissed him on the lips. Tears fell from his eyes, splashing into his brother’s mouth and dissolving the witch’s blood. It was not long before Peter opened his eyes and sat up. The searing burns across his face and arms and legs caused him to moan and suck in air through his teeth. His tongue lay swollen in his mouth and when he opened it to speak, his voice wheezed like a rusty hinge.

“Who are you?” he asked.

“I’m Nathaniel,” he said, “Your brother.”

“Ah, but you’re too old!” said Peter.

So Nathaniel explained everything, and as he spoke, Peter began to recognize familiar features hidden in the old man’s eyes and voice, perceiving beneath the wrinkled skin and white beard, the face of his brother.

“Nathaniel,” said Peter, “what have you done! Now you’re old forever!” Confused andfrightened, he began to cry.

“Don’t worry,” Nathaniel said. “The spell has been lifted. My steps back will make me young again. Tomorrow, we’ll be the same age and everything will be as it once was.”

Nathaniel drew Peter close and realized, while holding his brother, how long his arms had grown. He told him about the witch’s curse and described all of the events that had occurred during the past few weeks.

“Can you help me up?” Nathaniel asked, and Peter, fighting back the pain across his sun burnt skin, took his old brother under one arm and gently lifted him to his feet. “My legs are weak,” Nathaniel said, and laughed at having already forgotten what it was like to be young.

“If it’s as you say,” said Peter, “in a few steps you’ll be able to hold yourself up without my help.”

With his left arm wrapped behind Peter’s neck, Nathaniel leaned against his brother as though he were a crutch. They slowly made their way together and with each step forward Nathaniel anticipated a shift in his body, a tingling all across his limbs, or a shrinking sensation as though gravity were loosening its grip on him. But no change occurred and he remained an old man.

“You’re not growing younger,” said Peter.

“I know,” said Nathaniel.

They shuffled forward, kicking up small clouds of dust and carefully stepping over loose bits of dead grapevine. With glittering, frightened eyes, Peter caught sight of the corpses that lay partially hidden in the surrounding darkness. He shivered all over as though cold.

“Don’t look,” said Nathaniel, and covered the boy’s eyes with his thin brown hand.

Inside the castle, Peter helped his brother up the main staircase then down a long corridor toward their father’s bedchamber. Along the way, Nathaniel was compelled to stop before a large hanging mirror. Peter stood beside him and together, they gazed at their reflections standing side by side. Nathaniel leaned in close, so that his nose nearly bumped the glass. He gently touched his cheeks, his forehead, his beard and scalp as though trying to find his former face hidden behind the wrinkly, sagging mask. He drew back in order to see himself fully reflected. There was nothing familiar about the body he now inhabited and he kept glancing at Peter’s reflection to his left as a means to remind himself of how he once looked.

When they entered the king’s chamber, Peter and Nathaniel approached their father’s bedside. A candle stood atop the nightstand, illuminating the King’s sleeping face.

“Father?” Peter whispered, and the King woke with a start, inhaling a long, deep breath, his eyes fluttering.

“Nathaniel?” he asked.

“No,” said the boy. “I’m Peter.”

The King’s face took on a confused look. He fought off the haze of sleep still lingering in his brain and in a single motion sat up in bed, picked-up the candle from off the nightstand, and held it close to Peter’s face. His eyes grew large and shimmered with tears.

“How?” he asked.

“Nathaniel rescued me,” Peter said, and stepped aside.

Behind the boy, the King caught sight of a figure, hunched forward and dressed in tattered rags. For a moment, his senses whirled, believing some stranger had broken into his bedchamber. But in the next instant, his mind fit the puzzle together and a great terror, like nothing he’d ever felt before in his life, seized him – Nathaniel! Lifting the candle higher, his son shuffled forward from the darkness and the King’s face fell; his eyes glinted even more wetly and his hand trembled, dripping burning wax upon his wrist.

The King slid out from under the covers, swung his legs over the side of the bed, and, without taking his eyes off him, stood face to face before Nathaniel. He examined his son in the dancing candle light with a mixture of regret and fascination. As the shadows flickered across Nathaniel’s face, the King caught a faint glimpse of his son within the weathered features.

“I’m sorry father!” Nathaniel said.

And upon hearing the wheezing, raspy voice the King made a noise – “Ah!” as though someone had stabbed him, and in a single gesture, drew Nathaniel to his chest, gripping him with frenzied hands. An immense sadness swept across his heart at realizing he’d never hold the boy again.