“Tanner entered this painting in the 1898 Paris Salon exhibition, after which it was bought for the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1899, making it his first work to enter an American museum.”

– philamuseum.org

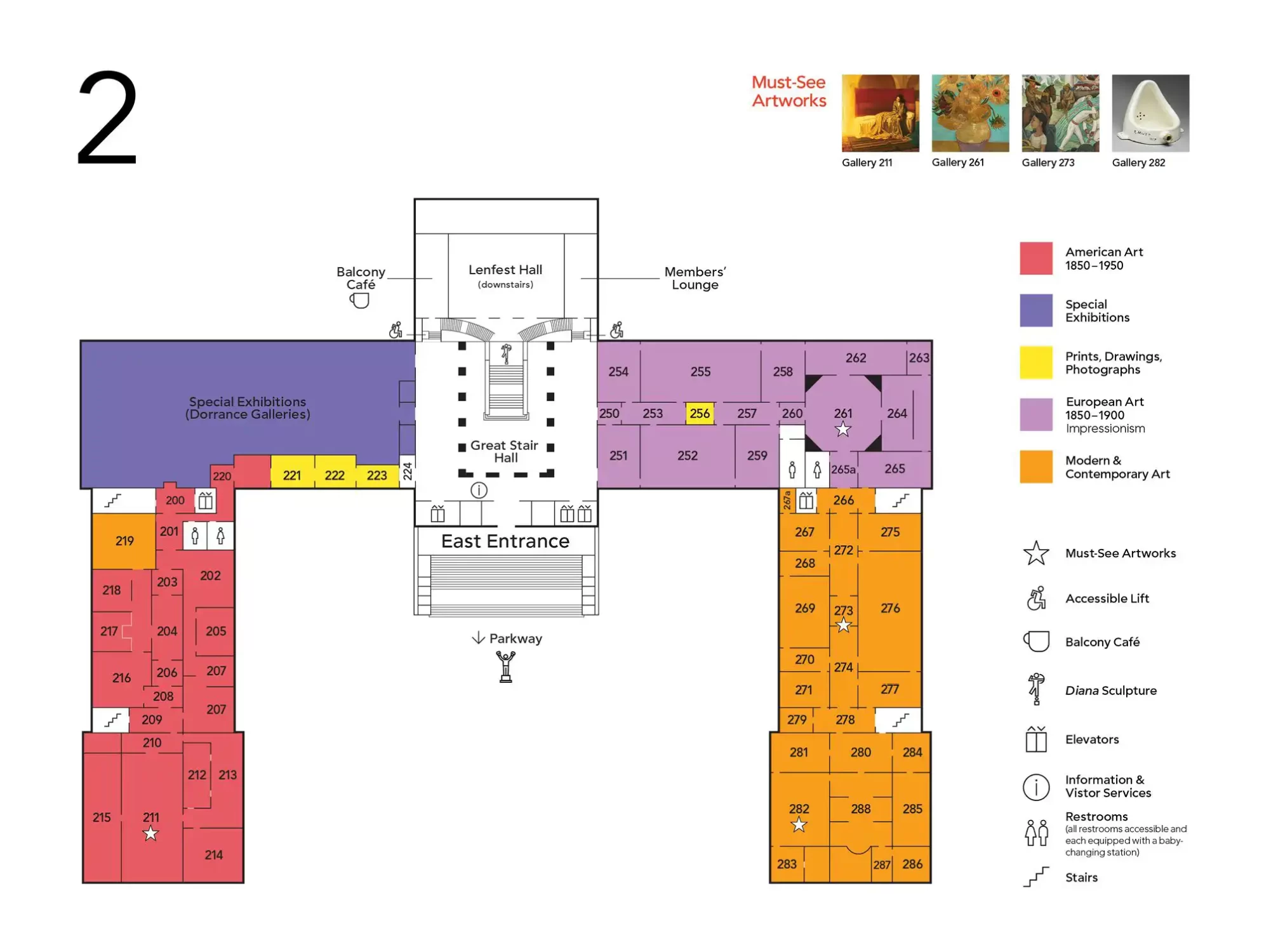

2nd Floor Map of the Philadelphia Art Museum. H.O. Tanner’s The Annunciation is in Room 211 on the left side of the room when entering from Room 215.

(Source: philamuseum.org)

Angle 1: South, Distant and Obscured

When viewed hidden behind a corner in the next room, there’s an astonishing life in it. The kind of life you see before something unexpectedly dies. Not an elongated demise, but a fist of death that quickly rushes out of the ether. A murder or a car accident. Something like this. I had been preparing myself for months. Every Sunday night in my bedroom, looking at a print of The Annunciation, focusing on the young Mary (her toes poking out from the blanket, the wrinkles in its fabric) and the Angel Gabriel (a yellow column of hovering flame). It had to be the last thing I did every night. First, I’d clear my room, put all signs of disorder away. Then, I’d light incense and place it on a stool to the left of the chair I sat in. Finally, I’d carefully remove a print of The Annunciation from its hiding spot behind a mirror leaning against the wall to my right. Careful of not viewing it before I am ready. Because it must be sudden. It must swallow me.

Deep breaths.

Eyes closed.

In, out, in, out.

When I’ve prepared myself, I remove the print and study it. I don’t know how long this goes on. I don’t keep time . . .

This entire ritual began the previous summer after my relationship with E ended. Structures within myself that I’d previously thought irrefutable suddenly dissipated. I hollowed out. It felt like opening a box full of electrical cords and realizing none of them worked. Yanking out one after the other and throwing them into the trash. No power. No function. My body felt like an exuviae. “I am nothing,” I thought. “I mean nothing and I have nothing. There is nothing inside of me. My whole life has gradually become a mistake.” Depression sneaking in, anxiety. I needed to find something meaningful. I reread Kurt Vonnegut, looking for something. In one of his final interviews, he says that it is important to grow the soul. The body becomes recalcitrant, a mineral without an interiority. The mind calcifies. Becomes a participle. Grow a soul, he says. I needed something, then. Food. Water. I was desperate. How do you grow a soul?

The painting initially came to me as a nostalgic object. At first, I looked at it and only thought of E, of how it had affected her. I longed for that aspect of her: her vulnerability. Because I was vulnerable, too. I could be blown over by a breeze and I wanted to borrow whatever stability or strength that I longed for in her. I wanted to be consumed by it. Often, I’d grow emotional just looking at the print and I’d have to put it away. Over time, this changed. It became less about E and more about something else. Something that was, for lack of a better term, religious. I’d created a ritual. I needed it. I relied on it. This ritual became the painting for me. I required it in order to view the work, to maintain the meaning it had for me, that it gave to me. The work was secondary. Marginal. Trivial Like E was, I thought as I was pulling into the parking garage on Eighteenth Street. I shook my head to clear the thought. Best not to dwell, I cautioned myself. Dwell. My lips formed the sound silently. I pulled into my parking space . . .

Unprepared, the painting is naked.

I stumble upon it unexpectedly in the Philadelphia Art Museum. I don’t allow it the regal sentimentality that I have been adding to it for months in my bedroom. This is not how things work, I think. The painting is naked but not ashamed of its nakedness. I am though. I want to see it clothed as I do in my room, when I look at my print. This is too much. I can see flakes of paint on the Archangel Gabriel. It feels like room shifts around me. I’m dizzy.

Angle 2: Southeast, Close Proximity and Hungry

When standing in front of the painting, it appears pale and sickly. It has had terrifying effects on me in the past. Quivering. Anxiety. Nausea. I viewed it two times before this with E. She first introduced me to the painting. We were sitting on a couch in a friend’s house, two months before we started dating. Our conversation had wandered into religious iconography and representation. She told me about Tanner’s painting and I was interested, so she showed me The Annunciation in a book of religious paintings. She told me how important it was to her, noting how young Mary is, how terrified she looks and the formidable, alien column of light that stands at the foot of her bed. I remembered shuddering. Later, I thought that it was because of E. Now, I wonder if she was part of something else. As much as I’d like her to be a storm I moved through, I wonder if she is in a different room, standing behind a door that I’d never thought to open . . .

You can Google The Annunciation, but I suggest seeing it in person at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I saw it in person there as we were approaching the cusp of our relationship. Only four months left. In that moment, E was standing in the center of the painting. Directly south of it. I stood to the lower right of her, southeast of the painting. She had one knee slightly bent, the other straightened and firm. She had been still for a long time. Small earthquakes around her eyes. Her shoulders rose and fell like a piston. Then, they stopped in a rise, conflicted as to whether they should drop or not. Her arms wrapped around her abdomen. It looked as if she were holding something heavy. I was unsure of what to do.

Once I would’ve pulled her into my body. Held her tightly and drank her scent through the nape of her neck. At that moment though a membrane had grown around her. Around me, too. She turned away and walked to the next room. I stayed. Looking back, it felt as if this was the moment we broke up. I stared at the painting. Part of me felt confrontational, wanting to know why it would do this to her. Another part was entranced. How did it do this to her? How could I do this to her?

Now, three months after we’ve separated, it does the same thing to me. The painting is paler than the last time, but no less effective. It is three o’clock in the afternoon and I’ve barely had anything to eat besides a cup of coffee and a pancake that morning. I’m hungry, but this is beside the point. My body grows

heavy under the eye of the painting. I’m sick, nauseous. The painting’s anemic complexion is making it worse. I can’t concentrate, so I go looking for the food court. The museum encircles me. Stairways lead to locked doors or bare walls. I think I’m heading downstairs. Instead I walk into a traditional Japanese home next to the room of a scholar from the Tang Dynasty. I look at my map and re- route myself. I think I’m heading to the main hall. Instead I wander into a room of Turkish rugs. The hunger pangs and nausea soften, then plateau. My stomach goes quiet. I wander through the rest of the museum, unable to find the food court until it’s too late. All the restaurants are closed, and the museum will do so in another half-hour.

Angle 3: Southwest, Seated and Hungry

Before closing, I manage to return to the painting. Intending to sneak up on it this time. To do it right. I’d made it into a religious object and I need to venerate it properly. To allow myself to reciprocate my own gesture with some modicum of peace and, thereby, expand my interiority. Grow my soul. But the museum disorients me. Never fails, too, and only more so now that my stomach is distracting me again. I can never quite understand where I’m heading. I think I’m approaching it from the side, but the painting catches me again. In the exact same way, too: peeking from behind the same corner from the same room. I put my head down, ashamed. Time travel would never work for me. Always the same mistake waiting for me to walk into it. I feel the painting watching me as I approach, and I study the floor. Still, I don’t know what I’m ashamed of. Is it regret? Do I think I’ve missed a moment? Had something offered itself to me and had I refused it? Had my stomach blinded me? I don’t know.

When southwest of the painting and seated on an ottoman, there is a supreme loneliness within it. Mary is frustrated or bored. I’m not sure which. She vacillates between these two emotions. She’s waiting for the Angel Gabriel to leave, but she’s also unsure of what it’s saying. It speaks a different language. Light communicates in a different dimension and, perhaps, she feels uneasy as she struggles to piece its strange syntax together. There is a dryness to it as well. It looks like a poster left in the sun, desiccated of color. However, I look away for two minutes and when my gaze returns, blood rushes to the painting and its colors incarnate and brighten. The yellow increases as it does when I look at my print. In the painting (as in my print) Mary’s stare grows more resolute while at the same time terrified. I think something else is being said. The language is difficult to understand. I try to piece it together, but I know I don’t have enough time. I feel that if I could stare at it like I do in my room, then I could sort everything out. If I could just pull the room around me, I would understand it and tame it. A guard announces that the museum will close in five minutes. Pack up your things and leave. And I do. This entire trip feels like a failure.

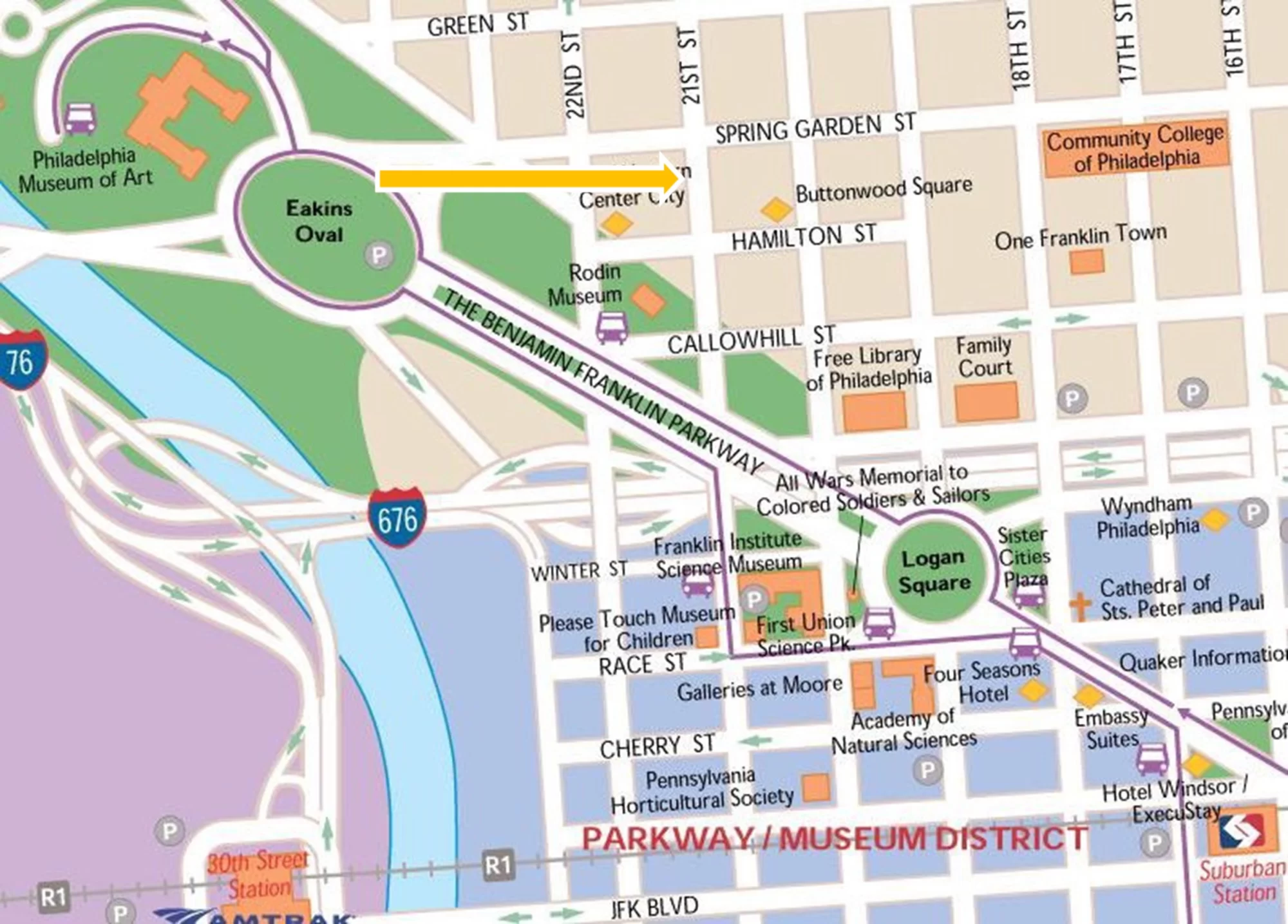

Museum District of Philadelphia. Orange arrow indicates my exit from the Art Museum.

(Source: philamuseum.org)

Angle 4: Multiple Angles (Windshield and Passenger-Side Window), Resignation

I walk out of the Museum, checking for directions to Eighteenth Street, where my car is parked. The painting follows me out. I walk down Twenty-First Street and see a coffee shop. I need something right now. I order a double shot of espresso and a croissant and sit down. I do a bit of reading. The painting settles over me, saturates my skin. I begin writing this. The painting has a delayed effect. I realize that its work is being done slowly. That the disappointment I felt after viewing it is maturity. The maturity of a vision. Something great lives within me, I think. I finish my espresso and walk to my car.

On the Ben Franklin Bridge leaving Philadelphia, when viewed out the passenger-side window, the city looks like Atlantis. The past, I think, the past is Atlantis. It cannot hold. It will implode on itself. Lights look like the tips of fingers poking above the water. I look out the windshield. Hundreds of glowing red mouths open and close. They grow and I brake. The bridge is just one loop among a series of interconnected geometric shapes, slithering one over the other in a community of snakes. I imagine myself as a snake. Sometimes they protect themselves by poisoning others.

When viewed from the front, the painting reappears in the ripening peach glow of sunset. Its yellow in retreat now. The column of light broadening over the horizon. I can understand Mary. I am frustrated. Her face. Her posture. E’s face. E’s posture. I think more should have been written, more should have been noticed. The farther away I get the darker it becomes until the peach has become indigo that the streetlights translate into black. I sigh. Not out of disappointment. There was something there. I know because it disappeared, and I felt it. It retreated. If I realize that it retreated, then I know it was present. I’m still carrying the shape of my past relationship in my stomach. It’s hard not to see myself as Mary. How are we not the same? I have my own column of light, my own Angel Gabriel at the foot of my bed . . . this idea follows me for months, dogs me over its dissolution, and refuse to release it to the wild. I ask myself how I could’ve not noticed it before. My head feels full of cotton. I imagine E. trapped there.

When the sky turns black, I realize that being aware of something’s dissolution means it once existed. The painting is doing its work. In it, Mary looks at the column of light and her face is a mixture of frustration, wonder, fear, pride, regard, humility, anger, and suspicion. I’m a convoluted soup of emotions. All of my life renders this recipe. Should it be any different now?

When I see my exit, I turn onto it and feel the painting’s arms retreat or lose their grip. Regardless, it’s finished. Its hands skitter on the highway and melt like ice on a skillet. I drive unaware of the change that has happened.

Later, after I’ve returned home, I go see a movie and study it for signs of myself. I’m aware that there is something revealed in the movie. Something about truth being concealed within the shape of lies. They are hidden in the cells of untruths. Gradually, as lies unravel, they emerge. Lies not being the evil I think they are. Simply skins that shed. The light makes them unnecessary. The light emerges from them. Mary’s face, mix of emotion that it is, goes through an evolution of expression because her response is a developmental process. At one moment, Tanner paints her as resistant, in the next fearful, in the next frightened, in the next confrontational. The painting is a palimpsest. To engage with it, I become as such. Skins peel off. The next week all the museums close. Along with all the schools and businesses. I was home. Thinking of the painting. Watching parts of myself peel off in the mirror.

I throw away the print.

I can’t look at it anymore.

The past has a smell to it. Oily and stale. What is there now? What is emerging? I seem to expand and fill every part of my house; yet, I am small. The grass and the road and the empty schools and buildings are small. The smallest things within us can destroy us. They are there every day. Sometimes you find them reflected in the mirror, in the curl of the paint, in the posture of another. Do we move away from them or through them? This question isn’t decided before things begin, but it is a part of the things that are.

The blade.

The light.

The fear.

It all converges in every single moment. It teaches you how to move through it. It punishes you. Rewards, I think, are for the dead—both those awake and sleeping.

Nick Hilbourn’s work has recently appeared in Maudlin House, Rain Taxi, and Prairie Schooner. He has two chapbooks of poetry: Pacha (Kattywompus Press) and Webster County (Alien Buddha Press). He writes about online poetry on his blog, largethingdslargerthings.tumblr.com and tweets (@nhilbourn) about it, too.

Hypertext Magazine and Studio (HMS) publishes original, brave, and striking narratives of historically marginalized, emerging, and established writers online and in print. HMS empowers Chicago-area adults by teaching writing workshops that spark curiosity, empower creative expression, and promote self-advocacy. By welcoming a diversity of voices and communities, HMS celebrates the transformative power of story and inclusion.

We have earned a Platinum rating from Candid and are incredibly grateful to receive partial funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, Illinois Humanities, Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, and Illinois Arts Council.

If independent publishing is important to you, PLEASE DONATE.