Eva is on her way to court to deliver closing arguments in her firm’s bulletproof case against Big Oil. This morning, after she pressed her pantsuit, combed fingers through her short hair, and selected her brightest, most professional shirt, her wife kissed her and said, “Kick their asses, babe.” Behind the steering wheel of her solar-powered electric car, she feels powerful. With this case, she will help roll back the clock on climate disaster so she can hand down a cleaner, kinder world to her own children, whenever she and her wife choose to have them.

At the first traffic light, her left-hand pinky finger tickles. When she glances toward it, expecting to find a stray hair dangling from the steering wheel to explain the sensation, instead she notices something wrong with her finger. The light turns green, and she has to focus on the road again, but, if she didn’t doubt her eyes, she would say the flesh of her finger had vanished somehow, leaving behind, not a bare bone, but a yarn-like squiggle. A pencil line where a finger used to be.

Training her eyes on the road, Eva resists the urge for a second peek. She’s afraid to look, especially now that three more fingers tickle, and she pretends she feels nothing at all in her toes.

By the second traffic light, the fingers of both hands still grasp the steering wheel but have no more substance than a child’s drawing, while the rest of her body continues to occupy its full expanse. As if the daily barrage of dieting ads and apps that scream at her to reduce, reduce, reduce, meant this all along: Stop taking up space altogether. Reduce from three to two dimensions.

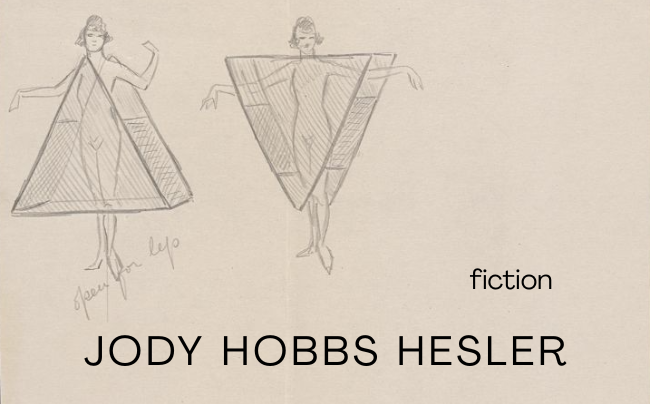

By the third traffic light, she glimpses her reflection in the rear view, startled to find a flat circle where her head used to be, a single line for her lips in an upturned curve, and symmetrical pencil swoops on either side of her head in place of hair, one forward and one backward J. A simple bow made of two triangles, attached in the middle with a square, gloms onto the center-top of her forehead.

The defense team is assembling in the courtroom now—smug white men with sleek suits and sickly grins, pockets lined with profits skimmed off the decimation of ecospheres. Their faces will erupt into laughter when she bounces in to join them with this static, vapid smile and insipid bow better suited to a child’s teddy bear.

If her briefcase is flat now too, how will she extract notes for her closing remarks? When she checks her passenger seat for it, she finds instead a bag of groceries that hadn’t been there before.

Next, an unfamiliar sound pierces the air. She swivels toward the noise and discovers two matching car seats in the back, holding two matching pencil-drawn twin girls, with smaller versions of her same hair bow perching at the tops of their smooth circle heads. These babies’ smiles gap open to show mirror images of single top teeth, and they gurgle with sounds that must be meant to signal delight.

If you believe their smiles, which Eva can’t quite, since her own lips, or lip, smiles without regard to her thoughts.

At the curbside of an unfamiliar pencil-drawn house, with pencil- drawn smoke chugging from its pencil-drawn chimney into a pencil- drawn sky puffing with pencil-drawn clouds and pencil-drawn sun rays and little pencil-drawn M’s of flying birds, she finds herself unfolding from the front seat of a giant, pencil-drawn SUV, wearing a pencil-drawn triangle of a dress and holding her pencil-drawn bag of groceries.

Her pencil-drawn twins toddle toward the house, which Eva somehow understands belongs to the three of them, and to a man off somewhere at work. Inside the pencil-drawn house, the pencil-drawn door clicks shut behind them, and the pencil-drawn knob disappears.

Jody Hobbs Hesler is the author of the novel Without You Here and the story collection What Makes You Think You’re Supposed to Feel Better. Her words also appear in The Pinch, Necessary Fiction, Gargoyle, Valparaiso Fiction Review, Atticus Review, Writer’s Digest, Electric Literature, CRAFT, Arts & Letters, and many other journals. She teaches at WriterHouse in Charlottesville, Virginia; writes and copy edits for Charlottesville Family Magazine; and serves as assistant fiction editor for the Los Angeles Review.