by Jael Montellano

Picture the 2011 film Melancholia’s opening; the slow-motion fall of the black horse, the suspended moths in midair, the electricity worming from Dunst’s fingertips as Wagner’s Tristan & Isolde score murmurs. This is my experience of reading Alina Stefanescu’s newest poetry collection, My Heresies, in this transformative period of time. Read under late capitalism’s fragmented timespace, fascism’s expanding flames, and my own reclaimed practice of presence, I have been both jolted and swathed into moments of surprise, rapture, and creativity.

It’s my tremendous pleasure to correspond with Alina about her new collection and share with all of you some notes distilled from this deep-bodied lyric perfume she has made.

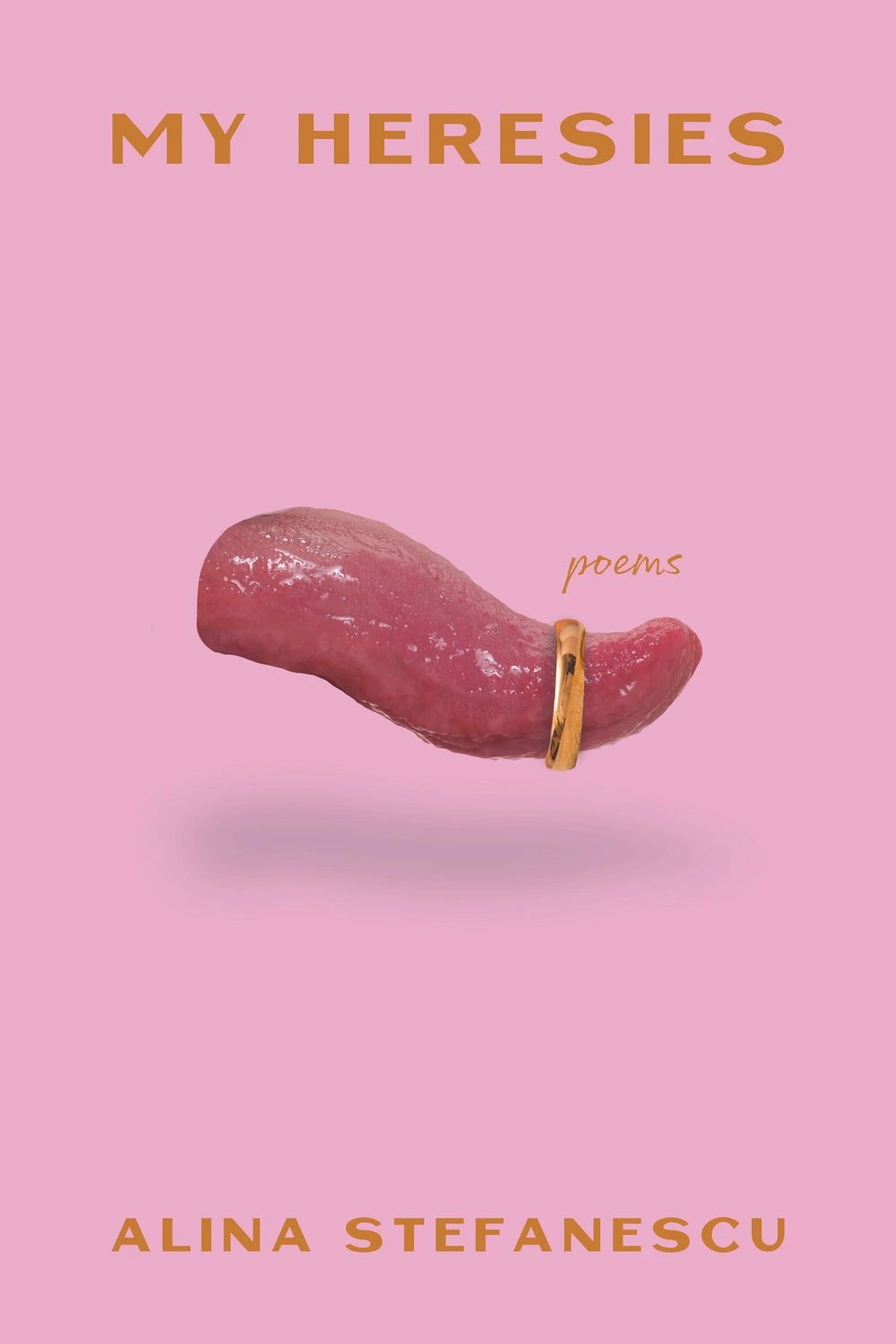

Jael Montellano: I hoped, with My Heresies’ libidinous cover, that it would brim with sensuous poetry, and it did not disappoint! Your poems, such as “Poem In the Key of C Sharp Minor” and “Revelation 18:24” are so hot! Do you consider your poems erotic? How is writing erotic poetry different from writing any other poem, or is it different at all? Talk to me about desire and eroticism in poetry.

Alina Stefanescu: Contemporary notions of selfhood are constructed by boundedness, boundaries, order, familiarity, structures that emphasize a perpetual state of tension. We position ourselves in thrall to this ‘self’-defense. When thought moves away from defending and sustaining the personal ego, it seems clear that the world is what we have at stake in each other. Nothing less than everything is on the table. Eros alters the conditions of knowing by using desire as a means of study. I’m thinking of space, time, how we move through it, and how poetry doesn’t fill the entire field of the page. Poetry moves across, between, around, within, expressing a spatial dimension that resembles a body, a physicality with the capacity to touch us differently and multiply. As with sublimity or religious experience, there is this possibility of ecstasy, of rapture, of being simultaneously inside and outside of a given moment or experience.

Thinking has always been an erotic experience for me. Everything I’ve written was conceived in relation to desire. Although some poems are more explicitly erotic, even the socialization poems emerged from that tension between saying and not-saying that puts a self at risk. My Heresies meets the contemporary notions of safety underwritten by boundedness (i.e. borders, eschatology, teleology, etc.) with an infinitude that resists closure. The poems cast their lot with insolubility and uncertainty. If there is no ultimate goal, then there is no final satisfaction— no culmination.

Our current political systems invest in catastrophe. When militarizing borders, ethno-states deploy apocalypse as an excuse to tighten the constraints on membership. Apocalypse, like the ethno-state, is utterly exclusivist. In counterpoint, eros and sublimity conspire in boundlessness. Queer theorist Leo Bersani has a phrase I love for touching without an aim to follow-through on something more, this touching for the sake of touching. “Non-teleological touching,” he calls it. Arousing without an expectation of relief or conclusion. A touch with no end is also a touch with no ending. What if the poem refuses to satiate our expectation of conclusiveness? The poet isn’t tasked with making authoritative conclusions. In this, we have a certain sort of freedom, duty, to imagine defiantly. I want potential proximities without happy endings. I want to be touched non-teleologically, whimsically, sincerely, by the hand driving the lyre. Inconclusiveness reminds us that things could be otherwise if one steps to the side and shifts the lighting. Perhaps we need this reminder now, more than ever. The present ‘reality’ gets read as the only possible world that can exist, with all roads leading us straight to this moment. But what if it isn’t? What have we done to our minds by accepting a given enshrined by teleology?

“Poem In the Key of C Sharp Minor” claims: “The lover is a tree.” It is the tree’s shadow that protects the speaker from the sun, enabling her to look up. And something indescribable happens in those small patches of darkness created by physical bodies. Shadows are a reprieve from the world’s continuous brightness. Eros allows us to disappear and exist, however briefly, outside the boundaries and boxes of modern selfhood. Perhaps religions deem this sort of experience heretical because ecstasy leaves no person to ‘save.’ “The tree and the child seek what is above them,” wrote Adam Zagajewski, a line that alludes to an innocence in this longing to be raptured. As I child, I cultivated this intense relationship with trees, whose canopies covered the maelstroms of wonder that descended when reading Emily Dickinson’s poems alone, under the dogwood, feeling that each of her ellipses was addressed to me.

“Dear reader, arrive full of desire on the scene of love,” wrote Willaim Morris. Anything can happen; the unpredictable weather may include our death. All too-close things have the possibility of destroying us. And sometimes, the poem wants to destroy the “Us”. Sometimes the work of the poem is a thunderbolt striking a tree. The tree’s body, the trunk, bears the marks of these encounters with lightning. In this, the body of the poem and the body of the author resemble the silence of the tree that summons you closer in order to read it. You close your eyes and run your fingers across the names and initials notched in its bark. Those are scars, spaces of singed flesh, gaps in the narrative whole that hide sidereals, and what could be more erotic than discovering the poems in those gaps?

You said about your prior poetry collection, Dor, that you were in conversation with ghosts. In My Heresies, you allude to writers such as Marguerite Yourcenar, Kafka, Matthew Zapruder, Tomas Tranströmer, etc. Was there a conversation you found yourself having in response to their work? Personally, I feel all poems are conversations. Do you agree?

Yes. This is why there will never be an end to poetry or music.

You read a book and pause suddenly, for there is a gap in the text that begs to be filled. You wonder if anyone else notices the shape of this gap, and how it maps on a fragment you read elsewhere. There is a sense of recognition, as if the author addressed this gap directly to you. A notebook opens. A door closes. The writer considers the question of sayability, what can be said, what is worth risking. A poetics of quotation acknowledges this dialogue by juxtaposing the words of multiple writers and texts, putting them in conversation with one another (as well as the author) thus orchestrating an encounter within the caesuras and gaps.

Literature alters the frame of saying; it asks to speak outside the given parameters. I mention light because it creates the shadows that become interlocutors. Poems often grow from a relationship with light that pays close attention to the way different bodies cast shadows. Paul Celan described his encounter with God as “a ray of light under the door of my hotel room.” Leonard Cohen swears a crack is how the light gets in. “Lightning is the lord of everything,” announced a man who may have been Heraclitus, or his fragments. Shadows are my tutors. I bring them to the page to continue a conversation, the way Samuel Beckett wandered to the pages that became “Dream of Fair to Middling Women” in order to dally with El Greco’s painting, The Burial of Count Orgaz, and its particular uses of light.

Maybe Dan Beachy-Quick remembered a window when he wrote, “Let those I love try to forgive what I have made.” This request seems different from asking them to forget what I have done. There is a desire to believe that the made object—the poem, the painting, the building (as opposed to its diagram or sketch) — is sanctified as a different form of doing. I made a cake. I made a book. I made a mess. All gods are guilty of their creations. All creations want to destroy their creators. Isn’t this why monotheistic gods are so jealous and rage-riddled? They know we can’t resist other gods, and it is this fascination with the other that threatens monotheism’s “Great God.” The author is guilty as charged. I’ll give you my head on a platter if you agree to let me write the story of how it got there.

“The poem is born dark; it comes, as the result of a radical individuation, into the world as a language fragment, thus, as far as language manages to be world, freighted with world,” said Paul Celan. There are many odes to Celan within your collection. What do you think about his sentiment of a poem being “born dark,” about the individuation and fragments of language in particular as they relate to bilingualism, your fluency in English and Romanian?

“Freighted with world,” yes! The poem is always en route, to quote Celan, whose neologisms include fergendienst, a word which Pierre Joris translated as “ferryman’s labor,” and which came to Celan while he, himself, was translating Osip Mandelstam. We are forever translating ourselves into and out of each other. The poem never stops moving, changing, shaped by the one who receives it. Religions and political systems conspire to ensure that we are born into the world of the fathers and damned by the future we inherit from them. But poems dig past the land titles and inherited deeds, past the snake of “sin,” and this digging, paradoxically, reveals a new sky, which may be an abyss, depending on whether you hang upside down from a tree branch when studying it.

Like Celan, language is critical for me. And I will often insert a line break against the syllabic beat in order to make the reading uncomfortable, to refuse the stanza’s music, to stagger the poem’s footsteps, making the poem unattractive. But what does it mean to “attract” the reader? A different bilingual writer dreamt of becoming a composer. In 1937, this man named Samuel Beckett wrote what became known as his “German Letter,” describing his abandonment of English for French as an effort to penetrate “what lurks behind” language. “More and more my own language appears to me like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at the things (or the Nothingness) behind it,” Beckett wrote, before railing against the idea of “official” language in art. Towards the end of the letter, like an unrecovered surrealist, Beckett harps on the importance of contingency and random error:

An assault against words in the name of beauty… Only from time to time I have the consolation, as now, of sinning willy-nilly against a foreign language, as I should love to do with full knowledge and intent against my own — and as I shall do — Deo juvante.

This notion of sin, and sinning against, is central to our constructions of heresy. The sinner is damned not by the act itself but by the classification of the act as unclean, an offense to the ruling order. I don’t want to make readers comfortable by assimilating foreign words or pretending that we can live happily inside a melting pot. That’s just not true for minor languages. They disappear, vanish like desert mirages. Since Romanian isn’t taught in US schools, my relationship to being Romanian exists solely within this language, its idioms and expressions, its legends and superstitions, its texts. I get why Emil Cioran elected to marry into a “major” language like French; the shame of being “minor” recurs throughout his writing. More importantly perhaps, this shame of being minor, or being Romanian, also led him to cast his lot with extremist nationalists and proto-fascists in his university days. Fear of being small or minor also underlies the policies of Make America Great Again (MAGA), the aesthetics of “tall and handsome and buff” masculinity, the eschatological fantasies of monotheisms, the late-capitalist image economy that bets on going ‘viral’ … even the existence of billionaires implicates us in these fantasies of greatness.

Against greatness and boundaries, poetry carries conversations across the shared homeland known as air. The sky is my byline, so to speak.

You have mentioned spending many an hour listening to your children’s piano practice sessions. You wrote a playful research document titled “32 Short Films About Erik Satie” and note the composer’s role as a phonometrician and write about music as having wet and dry sounds. I can’t help but think of how this applies to poetry, which is also in the art of making music. How do you apply this theory? What are some practical musical habits you have that assist you as you write?

Poetry owes Erik Satie quite a bit! Alas, I could yap about music until the clouds come home. Take the sound of a word like “percussion,” with its susurration, that hiss at the center. Percussion palpates; in its verb form, “to percuss” also refers to gently tapping a part of the body with a finger or an instrument as part of a medical diagnosis. Remember when pediatricians would percuss a knee your leg would snap up violently? Enter drums.

My understanding of light and darkness, how to use it, how to modulate it, was shaped by the experience of Stephen Sondheim’s musical, Passion (1994). Take the song, “Happiness,” for example, which opens by establishing its rhythmic constraint through the beating of war drums. These drums return at various moments in the song, sculpting the pauses and breaths, building friction within the lyric duet. Giorgio and Clara revel in “All this happiness” and its variations (“so much happiness”) as bugles and boots push back: order, rhythm, pace. The instrument of the human voice cannot overcome the powerful beat of the drums, the marching orders of war and national interest. Midway through the song, there is a turn wherein the two lovers begin singing over each other, their voices crossing. Giorgio refuses to imagine them ending: “I will summon you in my mind,” he insists, calling upon the epistolary to keep their love alive. “We’ll make love with our words,” he says, “You’ll be with me everyday, Clara.” The way Sondheim orchestrated this encounter calls upon every single sound, both existing and imagined, to build an unforgettable moment. Two lovers invest in hope, promising to meet again, as if passion and ecstasy can be domesticated or tamed into something as acceptable as mere “happiness.”

What is happiness over the long term? How does duration alter the nature of expectation, whether in the musical line, the poetic line, or the relational one? We’re back to those gaps where rhyme, too, becomes a kind of breathing space, a matched step, a breath that one line shares with another line. When we think about writing as putting words in relation to one another, proximity opens up the gaps between and within them, linking them through various figurations of sound (i.e. repetition, echo, rhyme, metre, etc). Rhyme divulges the possibility of consonance (or dissonance) between what words say and how they are said. But consonance is not identity, as Giorgio Agamben noted in The End of the Poem: Studies in Poetics. Sound has secrets, and this is the delight of studying it. I crave surprise, astonishment, and yes – confusion. Repetition that gives the sonic impression of similarity while landing in a different place. The word “it,” for example, could be anything; the epiphany could be a snail, the aftertaste of a violet, a solo viola.

“All poetic institutions participate in this non-coincidence, this schism of sound and sense — rhyme no less than caesura,” wrote Agamben. “For what is rhyme if not a disjunction between a semiotic event (the repetition of a sound) and a semantic event, a disjunction that brings the mind to expect a meaningful analogy, where it can only find homophony?”

I listen to music when writing. Or return to writing when listening to music. Or squat to jot down an image that occurs in a birdsong while walking my dog. Going back to the jottings and notes requires me to strap myself to the lonely mast of the thing going towards language. Loneliness has always been part of both writing and life for me, but there is a discipline to it as well. And there is the reprieve of being with others, existing in relation to cherished friends.

Ultimately, the precondition for intimacy is distance. We feel close because we know what it means to be far. “There are atoms, and the spaces between them; surmise makes up the rest,” Democritus said in Diogenes Laertius. These gaps relate to your earlier question about poems as conversations. How to describe the echo that bounces back and forth between the hard, stony sides of a deep ravine? How to communicate how it softens and changes when moving upward? How to justify studying and creating from these spaces of potentiality, these holes of sound, shadow, and emptiness?

One of the critiques Satie received was that he composed music without form, “solo piano pieces written in free time.” You write that he encouraged discomfort, which is very anti-capitalist. Talk to me about free time, about loitering, as an anti-capitalist practice. What role does discomfort play within creative practice?

Form is the given container that makes an object recognizable as music or art or poetry to others. Since critics rely on this sense of recognition as the source of their expertise, the book gets thrown at artists that are doing unrecognizable things. This urge to opt-out of the constructions of “order” and “success” can be traced through Dadaism, Situationism, anarcho-communism, and countless artistic movements that foregrounded decadence as an aesthetic resistance to the moral hygiene of the ruling classes. As Oscar Wilde said of the French Revolution: “To the thinker, the most tragic fact in the whole of the French Revolution is not that Marie Antoinette was killed for being a queen, but that the starved peasants of the Vendée voluntarily went out to die for the hideous cause of feudalism.” Loitering opts out of late capitalism’s linear momentum forward. When you don’t move along with the crowd, propelled by the maelstrom of hustle, you see the world differently. You see what we, as humans, are missing in our urges to win, conquer, and ‘succeed.’ And I think that is related to the way we construct order, or our association of safety with this feeling of knowing where we are going, having a destination, checking an item off a list, “fulfilling it.” Satie’s “free form” was seen as a threat to the established order of music: it didn’t have a clear purpose or goal. It loitered. It fucked around.

And that takes us back to eschatology, which sublimates the erotic urge to be lost in a feeling one cannot control, a feeling that culminates in the cessation of expectation. All rules and norms are suspended in the apocalypse. The end of days will be an ocean of violence. All taboo will dissolve in the excoriating blazes of the apocalypse. All personhood will be subject to the same impossible limitations. Duration, under these conditions, will become unspeakable. In the apocalypse, absolute violence meets absolute renunciation.

“I see my light dying,” Clov said to Hamm in Beckett’s Endgame. One must sit on a stoop and watch the light in order to notice this. One must opt-out of time. And this, for me, is writing’s provocation. I’m reminded of Robert Glück’s allusion to the influence of Georges Bataille on his work. “I’ll join the ritual when there’s human sacrifice,” Glück said to friends who wanted to bury a crystal on the beach in order to protest war. Perhaps invoking the radical community organized around Autocephale, Glück added: “In my writing, I want to display a self that disintegrates,” and this self must be compelled by something; it must have a hole through which “the world can enter.” A crack of sorts. A bolt striking a tree in a meadow outside of Paris. A way of breaking and being broken. “A meticulous account of lightning striking”: this is how Glück described his aesthetic. Something must happen: the writer sets the conditions for possibility. In the process, something is changed.

Every effort to construct a clearly-bounded literary self that fits the demands of neoliberal subjectivity and empowerment feminism is demolished by my actual existence. And there is art in that— there is something art-like about not being able to perform aesthetic purity. In failing. In trying. In losing and being so splendidly lost.

I thank you, truly, for this exchange and all its meditations. I’d like to end with something fun, and for the reader, a call to expansion. Go wherever you like with this, Alina: if My Heresies were a course, what would its syllabus contain?

O, now you have given me a feast, the night’s delight and the fugue’s undoing!

First there was thunder, followed by lightning striking a tree in a field outside the city of Paris, and a wonderful parentheses in Batailles’ book, The Tears of Eros, with its own gap, namely, the pause that surely occurred when Bataille sat in his study, editing his notes, before pausing suddenly to look up from the page and smile at something unavailable to the reader, before returning his attention to the typewriter and adding: “(but is it so decisively easy to grasp the difference between eroticism and poetry, and between eroticism and ecstasy?)”

When we glance at a ghost in the room, we aren’t praying for closure but setting our sights on the impossible, and agreeing to be apprehended by the unspeakable.

cloudscape i / cartography, mapped selves, & monuments

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (Passport), 1991 with instruction: “White paper (endless copies)”

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (Passport #II), 1993 with instruction “Print on paper, endless”

- A map of Birmingham where the indicated “landmarks” are limited to the sites of various graffiti tags. The tags are the “monuments,” the tributes, the sites of epic and history, the stories of a community that resists gentrification.

- Ryzard Krynicki’s poem, “Posthumous Journey (III)”, as translated by Alicia Valles

- Marina Tsvetaeva’s essay, “The Poet and Time,” alongside her poem, “Ars Poetica”

- Samuel Beckett’s “German letter” from 1937

cloudscape ii / the statecraft of selfhood

- “Epitaph for My Heart” by The Magnetic Fields

- Nicolas Frobes-Cross’ “The Evil Eye: An Interview with Alan Dundes” in the Cabinet issue dedicated to eschatology

- Beckett’s “My Family” from The Unnameable

- Karaoke performance of Cher’s “Just Like Jesse James”

- Forrest Gander’s “The Moment When Your Name is Pronounced”

- Lauren Berlant’s Desire/Love (Punctum Books)

cloudscape iii / sacred profanations

- “2. Reverent intensity” from John Cage’s notebooks

- The section titled “Lucidity” in Roland Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse

- Francesca Woodman’s Untitled, 1975-78

- Brian Teare’s “To Eros” (in Sore Eros)

- Auguste Rodin’s Satan embracing a woman (L’avenir) c. 1880

- Paul Celan’s neologism, wahnsinn, translated by Pierre Joris as “the madness of when” or “mania of the date”

- Jusepe de Ribera’s Saint Sebastian (date unknown)

- Joe Henry’s album, Scar (2001)

cloudscape iv / socializations & relationality

- “Scenography of a Friendship” by Svetlana Boym (Cabinet, Winter 2009-2010)

- Social scripts for autism spectrum disorder, both current and archival

- Pamphlets or short books intended to socialize teenagers into being a “true” version of whatever religion printed the pamphlet and invented the designated ritual or ceremonial acts

- “Kierkegaard, the Isolated One” by Paul Zweig (collected in The Heresy of Self-Love)

- John Ashbery’s “Laughing Gravy”

- Clare Connors’ “Derrida and the Friendship of Rhyme” (Oxford Literary Review 2011)

- Robert Glück’s “The Art of Fiction No. 260” with Lucy Ives (The Paris Review)

cloudscape v / soundscapes

- Samuel Beckett’s “Ping”

- Debbie Lisle’s “A Speculative Lexicon of Entanglement” (Millenium: Journal of International Studies, 2021, Vol. 49, 3)

- Mark Strand’s essay, “On Nothing”

- A slideshow of images conversant with My Heresies, accompanied by various songs

- David Metzer’s “Modern Silence” (The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 23, No. 3, Summer 2006)

- Three Dialogues: Samuel Beckett and George Duthuit

Alina Stefanescu was born in Romania and lives in Birmingham, Alabama with her partner and several intense mammals. Recent books include a creative nonfiction chapbook, Ribald (Bull City Press Inch Series, Nov. 2020) and Dor, which won the Wandering Aengus Press Prize (September, 2021). Her debut fiction collection, Every Mask I Tried On, won the Brighthorse Books Prize (April 2018). Alina’s poems, essays, and fiction can be found in Prairie Schooner, North American Review, World Literature Today, Pleiades, Poetry, BOMB, Crab Creek Review, and others. She serves as editor, reviewer, and critic for various journals and is currently working on a novel-like creature. Her poetry collection, My Heresies, was published by Sarabande in late April 2025. More online at www.alinastefanescuwriter.com.

Jael Montellano (she/they) is a Mexican-born writer, poet, and editor. Her work exploring otherness features in La Piccioletta Barca, ANMLY Lit, Tint Journal, Beyond Queer Words, Fauxmoir, The Selkie and more. Her nonfiction essay “The Sea, the Shell & the Pearl” was nominated for 2025 Best of the Net. She is the interviews editor at Hypertext Magazine, practices a variety of visual arts, and is currently learning Mandarin.