by Eileen Favorite

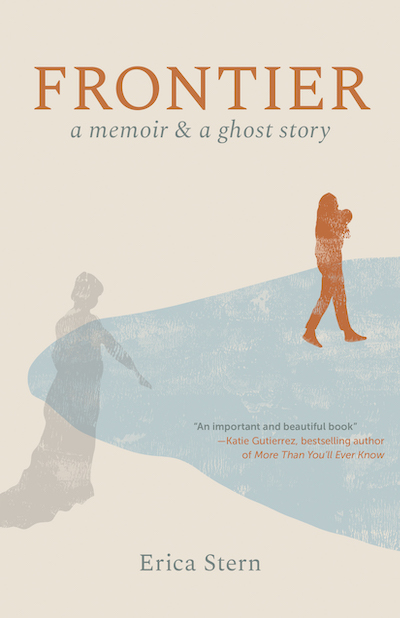

Like every mother, Erica Stern hoped for a smooth, empowering experience for her first child’s birth. But complications arose during labor, depriving her son of oxygen. In her hybrid work, Frontier: A Memoir and a Ghost Story, she describes the anguish of birth trauma and the distress of not knowing how her son Jonah’s health would be impacted. Stern describes with unadorned clarity the early postpartum days, how her bonding experience was derailed by his stay in neonatal intensive care, and the aftermath and struggle of reconciling the meaning of such an event. Blending memoir and research on the history of birthing practices—from traditional midwives and homebirths, to Victorian-era sedation, and the current elevation of natural childbirth and baby-brand culture—she examines how these models disempower women. The book also includes a fabulous Wild West ghost story that mirrors the sense of haunting failure and terror too often present in a woman’s transition to motherhood.

Eileen Favorite: I was struck in the book by how notions of control, magical thinking, spirituality, and the limits of medicine intersect, as they often do when it comes to birth. Your journey with Jonah has elements of all these ideas. How did your experience with or belief in the medical system evolve?

Erica Stern: I had such a naive trust in the medical system. I felt like once I entered the hospital and was hooked up to monitors, doctors would be able to correct any issue we encountered. I was caught by complete surprise when things went so off course. At no point during labor did I have any inkling that a brain injury was a remote possibility. That was something that happened to other people in other times and places. So, when we got the diagnosis, it did feel like a force from outside sweeping in and changing my reality. I can remember this distinct sense of disbelief, that what I was hearing could not possibly be true. Because it was an injury–there was a before and an after–I felt I should somehow be able to turn back time and return to the other reality. It was unbelievable to me that the prognosis was out of my control and that I couldn’t press undo.

The doctors couldn’t tell you how his brain injury would manifest in the long run. They couldn’t predict anything, which made it seem up to the “gods” or up to “luck” or up to the magic of Jonah himself.

We were told a lot of versions of “time will tell” which, as an impatient person, was difficult to hear. I wanted to fast-forward, to see what my kid would be like in a year or five or ten. The magical thinking snuck into that vacuum.

There’s a moment before you receive Jonah’s MRI results, when the rabbi was with you, and he offered to pray with you. And Jed was like okay, I’ll pray, which wasn’t something he did regularly.

Jed is Jewish, but an atheist. At that point we were grasping at straws, doing anything and everything as a way of searching for control. It was helpful to have little things to ground us: prayer, even pumping milk. But it can be dangerous, as well, to look for a way to exercise control when you ultimately have none.

I went through ten years of infertility and three miscarriages before I had my kids. So I can relate to a lot of this feeling of disempowerment, not having any control, and then watching other people just glide through the maternal experience without a hitch.

It took a while not to view all the other mothers around me as in opposition to me and my experience. It was hard to do little things, like taking Jonah to the pediatrician and sitting in a room of other new mothers with their babies.

It took me years, and writing the book, really, to see how trauma can cut off compassion. I spent so much time and energy focused on what had happened to me and feeling burdened and isolated, wondering, why had I been chosen? Then I started to listen to others, and I realized many were carrying around so much. I met women who had experienced traumatic births or who had children with disabilities or who had encountered serious medical issues during birth or after. I wasn’t on my own.

Having these kinds of experiences changes you as a parent. I care less about outside markers of success–like milestones and test scores–than I might have otherwise. I’m more grounded in the present, watching the interesting, unique people my kids are becoming.

The upside of trauma is that it gives you perspective. Because nothing will be as bad as what you experienced in the delivery room and afterward. You were questioning whether you were going to be able to bond with Jonah. As a reader, I knew you would, but I empathized with that fear. You also talked about how nobody prepared you for this birth experience.

People tend to go into delivery with blinders on, because focusing on the risks would be overwhelming. But some of the naivete for me came from how birth is communicated to expectant parents, and I think there needs to be more emphasis on the wide spectrum of birth experiences, including risks. People are starting to talk more openly about their births, and there’s more writing about it too. So I think we’re moving in a good direction.

How does consumerist culture also play into the illusion of childbirth?

The baby-industrial complex and consumerist culture produce this Disney-fication of motherhood and birth and parenthood. Pregnant people are so steeped in baby registry guides and Instagram influencers promoting this idea that they can curate the perfect birth and postpartum period and childhood. All you have to do is buy the right breast pump or stroller.

Behind this veneer, though, there’s no real support system for parents. Looking back in history, there were more real supports–whole communities working together. I don’t want to sugarcoat the past; maternal and infant mortality were high (something I explore in the book’s fictional thread), and women were very constrained by societal roles, etc. etc. But, now, in America, in place of actual support, we’ve got this economy that tricks people into thinking the ease of motherhood can be purchased.

Right, you get a video monitor, or a cradle that rocks itself, instead of an auntie or a grandmother.

Exactly. Also the marketing imagery that goes along with the video monitors or self-rocking cradles peddles this sanitized image of birth and early motherhood that can seep into maternal expectations. So not only do the objects not adequately replace the actual supports but they provide a false ideal of what birth and the postpartum period will be like.

There’s a moment when you’re going down the hallway to find out the results of Jonah’s MRI and you’re saying, “I will always be walking down the hallway.” You capture beautifully how memory works in trauma, and how the immediate experience of trauma registers in the mind. The surreality of “I’m not supposed to be here. Why am I here? I’m only half here. This is the wrong world. This shouldn’t be happening to me. Wait, this is happening to me?” You talk in the book about how you felt this dissociative split during Jonah’s birth, and that you went into the vent above. Did having a second baby help you to heal that split?

It allowed me, not to leave the trauma behind, but to realize that there was more beyond the trauma and, also, to stop holding Jonah inside the trauma. In the early years of parenting, he was wrapped up in that story. It was hard to separate the baby from the birth experience and the grief. Having a different birth experience with my second son freed me from making the birth so central to Jonah’s story.

So Frontier is a hybrid work, the memoir of Jonah’s birth, and a ghost story of a frontierswoman who dies in childbirth. How did you get to writing a ghost story?

I didn’t think I was going to write a ghost story. At first I wrote from the perspective of a woman who dies in childbirth–she was a version of me, a thought experiment: What if I’d given birth in the Wild West? I quickly wrote her death, which seemed to me the likely outcome in that time and place, but I wanted to keep telling her story. The only way I could think to do that was by making her a ghost.

And the ghost/narrator starts driving her husband’s second wife mad by haunting her after she gives birth. Which was really mean (LOL).

I don’t know that the ghost had bad intentions; she wanted to find her child. The second wife was also a version of me, a woman who can’t fully connect to her child, who doubts her role as a mother, who feels that somehow things are not going as planned even though she has a living baby. I too felt extremely ambivalent about motherhood at the beginning. I didn’t know that I wanted to parent a sick child.

The second wife senses this spirit hovering above, which destabilizes her.

I think that happened to me, in a way. I was reliving that moment in the delivery room, but also going about my daily life. It was a split screen version of reality. Only for me it was two versions of myself–past and present–instead of a woman and a ghost. I could make the feeling literal through an actual haunting, which is the great thing about fiction.

The ghost story aspect dovetails nicely, not just with all the issues around birth and women’s health, but also around issues of spirituality and how we construct meaning around difficult experiences.

Judaism has always been important to me, but I had no idea this book would become as Jewish as it is. But going through something that shook me to my core made me go to my roots. In trying to navigate and process this traumatic event that turned so much upside down, that’s where I turned.

Those rituals are very comforting when you don’t have the bandwidth to make certain decisions. The religion has already contemplated the issue and has a ritual. You sang the prayers in Hebrew when you didn’t really understand them. I think that’s beautiful because it’s just about how the rhythm of language has this incantatory power.

It’s absolutely about the power of the sounds, and also knowing these are words people have been reciting since antiquity to help them through difficult times. The ritual provided a path when I had no idea what to do; it gave me a set of steps to follow when I could not figure out a way forward.

Part of what I find compelling, though frustrating, about Judaism is how the tradition withholds clear answers. As a kid, I remember asking, where do we go after we die? And not being given a clear answer. It frustrated me because I wanted something solid to hold onto in the face of a thing that scared me. But there’s so much truth to the way the religion acknowledges uncertainty as a core part of existence. Ultimately my experience of birth was very much about sitting in uncertainty, and not just about Jonah’s future. Doctors could never clearly explain why the injury occurred or when, exactly, it had happened during labor. Judaism provided a template for tolerating that kind of open-endedness. It made it easier to let go of the need to find a reason, a why or a how. Maybe there’s no reason. That’s okay.

That’s so true. Because you can hear a lot of pat or shallow answers in some Christian sects that everything happens for a reason. If you’re the one experiencing the trauma, then you’re like, what possible reason? What kind of God would want me to go through this? And somehow that idea of “reason” makes you start to believe that others are “blessed,” which means you’re “cursed.” So to say in Judaism, there may not be a reason, that there is no answer, feels deeply comforting and less punitive.

It was a relief to discover I had a framework for understanding the world that wasn’t so punitive. Even so, it took me a long time to fully let go of the sense of culpability, the feeling that I was somehow to blame for my son’s condition. Those things are so much a part of our culture’s approach to motherhood that they are hard to escape.

I had no idea that birth would lead me into this sort of philosophical terrain. I was prepared for sleepless nights and lots of laundry and colic but not for being thrust into questions of agency and guilt. I guess birth really isn’t for the faint of heart.

But aren’t we the wiser for it? Maybe at the very least, you were meant to share this story.

Erica Stern is an essayist and fiction writer. Her debut book, Frontier: A Memoir and a Ghost Story, came out from Barrelhouse Books in June 2025. Her work has previously appeared in journals such as Mississippi Review, The Iowa Review, and Denver Quarterly, and has been named a finalist for the Noemi Press Book Awards and the Mississippi Review Prize, among other recognitions. Erica has been awarded fellowships and residencies from the Vermont Studio Center, the Martha’s Vineyard Institute for Creative Writing, and the Virginia Center for Creative Arts. She received her undergraduate degree in English from Yale and her MFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. A native of New Orleans, she now lives with her family in Evanston, Illinois.

Eileen Favorite’s first novel The Heroines (Scribner) was named a Best Debut Novel by The Rocky Mountain News, and has been translated into five languages.The audio version was nominated for best recording by the American Library Association. She received a 2021 Illinois Arts Council Award for nonfiction. Her essay “On Aerial Views” was named a Notable Essay in the Best American Essays 2020, and won First Place in the 2019 Midwest Review’s Great Midwest Writing Contest. Her work has appeared in many publications, including Chicago Magazine, Essay Daily, Fiction Southeast, The Chicago Tribune, Triquarterly, Hypertext, The Rumpus, The Toast, Belt, Chicago Reader, Poetry East, and Diagram. She’s been nominated for a Pushcart Prize for both fiction and nonfiction. She teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she received the Karen and Jim Frank Excellence in Teaching Award in 2020. Her class Love the Art, Hate the Artist has been featured in The Chicago Tribune, and her opinions on the subject have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, WGN Radio, WBEZ Chicago Public Radio, and The New Yorker. Her TEDx Wrigleyville talk on Love the Art, Hate the Artist, is available at her website. She lives in Chicago with her husband and two daughters.