by Jael Montellano

There is a new dominant presence in my household waking my awareness to wildness. She has four padded feet, an autumnal sable coat, and burnt sienna eyes on the edge of her black mask. She’s a brazen savage, a wondrous beauty, a mini Malinois. Experiencing life alongside her is an exercise in stamina, instinct, discovery and presence.

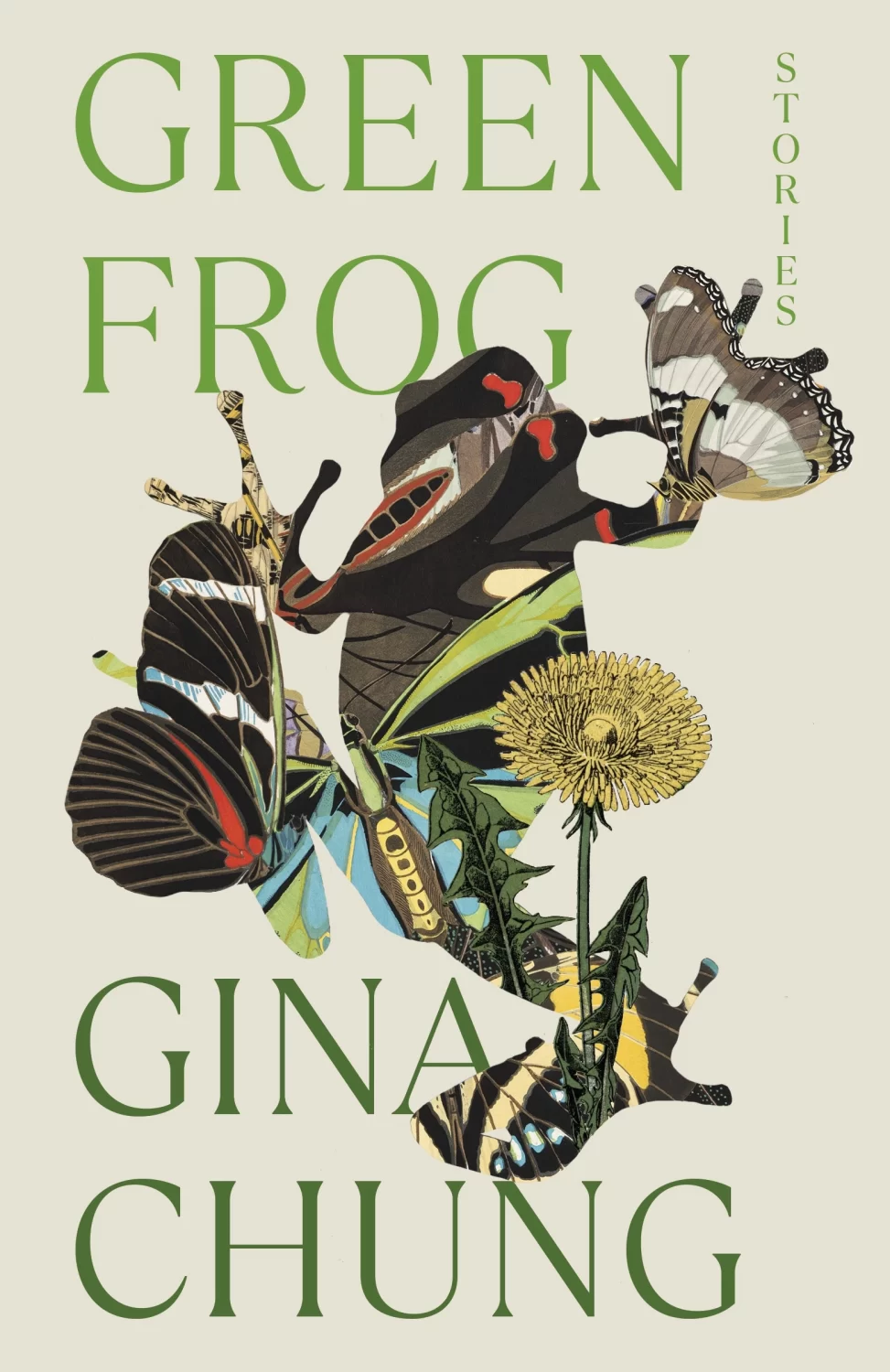

She teaches me about wildness and non-human wisdom; the same kind of wildness and wisdom Gina Chung captures in her new collection Green Frog (Vintage Books). In it, we encounter stories about Korean Americans uploading their memories to the cloud, fox demons avenging familial loss, AI clones dreaming of mermaidhood, and more.

Gina graciously corresponded with me about Korean folklore, animals, diaspora communities, and the magic of short stories.

Korean traditions are rich with vibrant folktales and mythology, like the kumiho in your story “Human Hearts.” What favorite folktale did you grow up with and how did it get passed down to you?

I was a very dramatic and lonely child, and growing up, I was obsessed with stories about daughters who were called upon to save their families or communities in some way. One such story in Korean folklore is the tale of Shimchong. Shimchong is the daughter of a poor, blind widower, who, because of his condition, cannot work, and has to beg for money and food to feed himself and his child. One day, when Shimchong has grown to become a young woman, the blind man learns that if he offers a huge number of rice sacks (which he cannot afford) to the local temple, he will get his eyesight back. Shimchong then agrees to join a merchant ship that is seeking a young maiden to sacrifice to the Dragon King of the seas, to grant them safe passage, in exchange for the rice sacks that she believes will cure her father. She jumps overboard into a stormy sea, and miraculously doesn’t die. She is ultimately rewarded by the Dragon King for her filial piety, and even reunited with her father, who also conveniently gets his eyesight back (though it’s unclear whether it was because of the rice sacks). I think I first came across this story in a picture book I had of Korean folktales for children, and it has clearly haunted me over the years. While it has a happy ending, it’s fairly disturbing. But I was very taken, as a child, with Shimchong’s bravery, and it’s also interesting that her sacrifice results in her having this kind of hero’s journey arc that female characters don’t often get to experience in these old stories.

Some of the stories within Green Frog contain elements of body horror; you have “How to Eat Your Own Heart” wherein the protagonist is cutting out their own heart, cooking and digesting it, “Human Hearts,” which reverses the horror perspective from human-turning-into-creature into creature-turning-into-human, “Honey and Sun,” where the twins are being starved, pinned, and abused into shape. What is it about body horror that lends itself to folktales, in particular as it relates to womanhood and embodiment?

I think body horror can be such a rich way to tell a story about what it’s like to exist in a body that is often contested, marginalized, or legislated. Your question also makes me think about how so many folktales contain body horror, particularly for girls and women. So much of what happens to our bodies is outside of our control, from the moment we are born. And the forms of violence that we experience aren’t always overt. A lot of these stories came from me wondering about how girls and women raised with or within violence might come to enact that violence upon others or themselves. That can often take the form of body horror, which can be very cathartic to encounter in art, since it offers us a sense of control that we don’t have in the real world.

There is a wildness in your stories that I find thrilling, overtly in anthropomorphism such as the stories “Human Hearts” and “Mantis,” but also in smaller ways, like catching lightning bugs in “Names for Fireflies,” and Ellie saving the moths in “The Sound of Water,” that seem to be saying, return. That there is wisdom in the wild, in the wood, in our ancestors and our homelands, distant from the stratified order and control of the patriarchy, that is grounding and necessary for our bodies. What does wildness mean to you and why is it important to return?

I love this question because I think my interest in incorporating animals and the natural world into my fiction comes precisely from that longing for wildness. We all carry around with us forms of knowledge that, as you say, are deeper than we know, and much, much older than we are. I don’t want to romanticize the past or imply that things were better back in the day, because in a lot of ways they weren’t, but I do think that pre-capitalism and industrialization, humans did live more in keeping with the natural rhythms of the world. I’m very much an indoor person in some ways, so I actually don’t think I would do very well at all in an entirely wild setting (I always say that I would be among the first to die in a zombie apocalypse scenario), but I do think it’s important to stay connected to that wildness in some capacity, since it links us to non-human animals and the world outside of our screens and homes. There is more to life, to this world, than we can ever know, and I think retaining a relationship to our wildness helps us live with and process what we cannot understand.

I am endlessly fascinated by the way we mythologize our silence. By this, I mean the things humans fear to say. Many cultures do this in their stories and in their language; instead of talking directly about a person’s anger, they are possessed by a demon, instead of saying a person is dead, they are sleeping. In your story “Honey and Sun,” the twins’ talking dolls Cardamom and Sage become replacement presences for an absent father and a neglectful mother. How do you navigate which parts of a story to mythologize? Describe a little of your process.

A lot of my writing comes from asking myself “What if?”. In the case of “Honey and Sun,” I started off writing about this pair of twin sisters in the first person plural, which was very fun for me, but because they are left to their own devices much of the time, I decided they needed another set of characters that could step in and interact with them. I was an only child for the first nine years of my life and I remember often being bored when I had to play on my own, and I was never really into dolls, because I always wished they could talk back to me and tell me what they thought and felt. So in some ways, the talking dolls in that story came from that early childhood wish, and I wondered, “What if the twins had dolls that could talk to them, and tell them all the things they wish their parents would say?” I also knew that I wanted the dolls to have fairly distinct voices from one another, so that helped with shaping their personalities and how they interacted with the twins. And because they’re dolls, they don’t really have all their facts straight. They’re kind of making it up as they go along, and because the twins are children, they just accept it.

There are three dozen lines I jotted down for their sheer power and truth, but a truth revealed more easily to refugees, migrants and children of migrants that have left a homeland and family behind. One of these lines, for example, is from “How to Eat Your Own Heart,” and reads “being able to know the first names of your elders is a luxury.” As a child of immigrants, what was important to you to convey about your family’s experience and the Korean American community’s experience at large?

With that story in particular, I was thinking about how I know very few of my relatives’ names, including my grandparents. It’s written down in our familial records, but I don’t really have access to that knowledge on my own. One of the reasons for that is because in Korean culture, there are a lot of different terms for your relatives, all based around things like what side of the family they might be on, how old they are in relation to one another, if they are related by marriage, etc. And you would never call an older relative by name—it would be considered very disrespectful. Another reason is because of what you mentioned, regarding what is lost when a homeland is left behind. Diasporic longing is something I am always thinking and writing about, as well as how one’s understanding of a language or culture can be sort of frozen in time for immigrants and the children of immigrants. I don’t want to speak for all Korean Americans of course, but there are definitely commonalities and shared experiences, including the fact that as a people, we have experienced centuries of war, occupation, and the partition that resulted from the Korean War. That is a huge national trauma that has had reverberations across our community. As a writer of the Korean diaspora, I see it as my responsibility to carry those things and do my best to remember them. And even if I’m not engaging with that history explicitly in a given work, I feel that it informs everything I write.

Some of the stories within the collection have very marked, dramatic endings and others arrive quietly at their fin; some are magical realism and some are the very marrow of Korean American communities down to the local church, some are written in first-person, third-person, second-person, and even village voice. How did you put this collection together? What did it teach you?

I actually didn’t originally set out to write a collection, but I realized at some point that I had amassed what felt like a sizable number of short stories over the years, and when I looked at them side by side, I realized that they shared a lot of themes in common with one another, despite some being more magical/speculative and others being more true-to-life. At the time, I was also working on the manuscript of my first novel, Sea Change, and when I began the process of querying literary agents, I reached out with both of my projects, saying that I had both a novel and a collection of stories. Once I signed with my agent, we discussed how to order the collection, and after the books sold, my editor and I discussed the order of the stories, and we also decided that I would add a few new ones, since many of them had appeared in journals previously. It was really fun to revisit those previously published stories and have the chance to tweak them, and even change around some of the endings. It taught me that changing the way a story lands or feels for a reader doesn’t always have to be this big thing requiring a huge overhaul—sometimes it can be as simple as adding a few additional lines, changing a few words, or returning to an earlier moment in the story that maybe held the key to understanding how it was going to end. It also taught me to think about how the order of the stories in a collection can totally impact the way a reader experiences them—my editor was the one who suggested leading with “How to Eat Your Own Heart,” which I think was a great idea, since it feels a bit like a calling card for the themes in the book.

Though I write across forms, I’m personally an avid promoter of the short story; for me, it’s the most perfect form, even if it isn’t the most popular seller. There is something about a short story’s ability to compress and conversely expand time that is mythic and magical—it’s cognate to oral storytelling techniques. You employ this time compression technique across many of your stories. Can you talk about this technique and short story writing overall?

Time is such an important element in fiction writing, because it drives everything. As a writer, you can play with time by speeding it up, slowing it down, skipping over vast swaths of time entirely, going backwards, etc. in a way that you can’t always get away with in a novel. I learned about time compression in my MFA program when I was first learning how to write short stories. I kept agonizing over how to get my characters from Point A to Point B, and then I realized that I could just… do it. You can just move your character from one scene to another with a simple space break and time shift, and you don’t always have to explain how they got there.

Short stories are my first literary love, and there really is something just so satisfying and magical about a well-crafted short story. It’s like a pocket universe unto itself. When I’m writing a short story, I often feel like I can be more experimental and exploratory than I might be with something longer. Writing fiction sometimes feels like I am trying to learn how to be someone else, to inhabit my character, and when I’m doing it for a novel, it can feel very intentional and deliberate and even method, at times. For short stories, though, it feels more lighthearted and playful, like going out for a night and using a different name at the bar.

Whose work are you studying at the moment that you would like to share with readers and what is firing you up about their work?

I am currently reading the short stories of Bora Chung, translated by Anton Hur, which are just fantastic. Her first collection, Cursed Bunny, is full of body horror, and is also very funny. Her latest, Your Utopia, is a bit more sci-fi, since it engages with things like AI, machinery, and tech (which feel horror-adjacent to me, especially nowadays), and I just got a copy of it and can’t wait to dive in. I am also very excited to start the new Helen Oyeyemi novel, Parasol Against the Axe. She is such a delightful writer who, speaking of playfulness, always reads like she is just having the most fun on every page, and she is not afraid to be hyperspecific in the strangeness of the worlds and characters she creates. Another writer who inspires me is Annie Dillard, whose craft book The Writing Life was deeply inspiring for me. I’m reading her Pulitzer Prize-winning Pilgrim at Tinker Creek at the moment, and every sentence is so densely layered and full of wonder that it makes me feel breathless at times—reading her reminds me that paying attention is one of the most important skills that writers can hone.

Gina Chung is a Korean American writer from New Jersey currently living in New York City. She is the author of the short story collection Green Frog (out March 12, 2024 from Vintage in the U.S. and June 6, 2024 from Picador in the U.K.) and the novel Sea Change, which was longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, a 2023 B&N Discover Pick, an APALA Adult Fiction Honor Book, and a New York Times Most Anticipated Book. A recipient of the Pushcart Prize, she is a 2021-2022 Center for Fiction/Susan Kamil Emerging Writer Fellow and holds an MFA in fiction from The New School.

Jael Montellano (she/they) is a Mexican-born writer, poet, and editor. Her work exploring otherness features in ANMLY Lit, Tint Journal, Beyond Queer Words, Fauxmoir, The Selkie, the Columbia Journal, and more. She is the interviews editor at Hypertext Magazine, practices a variety of visual arts, and is currently learning Mandarin.