by Lorraine Boissoneault

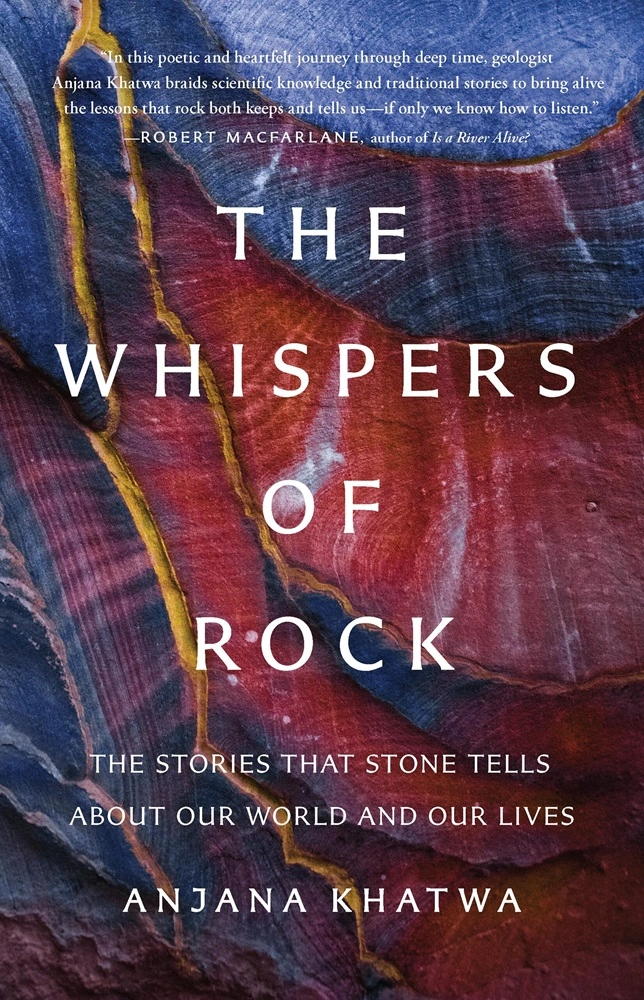

What do you see when you look at a rock? For geologist Anjana Khatwa, every rock is a reflection of the world and an opportunity for a relationship. In her stunning book The Whispers of Rock: The Stories That Stone Tells About Our World and Our Lives, Khatwa weaves stories of her life with the science of rocks and the traditional Indigenous knowledge that has been passed down for millennia. From the ways rocks shaped human evolution, to the dangers they pose (be it landslides, volcanoes, or the poisoning of waterways), Khatwa’s book offers continuous surprises and delights. I left feeling a deeper connection with the ground beneath my feet and the belief that we need to better understand these overlooked sentinels and the ways they shape our lives.

Lorraine Boissoneault: In the opening of the book, you write, “I went in desperate search of my dharti–a Hindi word which describes the grounding of oneself through soil, rock and land.” It’s a really moving way to start a very personal book and I’m curious how writing it was part of that process of your search for dharti.

Anjana Khatwa: Dharti is a derivation of Mother Earth, who has almost 21 incarnations in Hinduism. She embodies everything that we value that helps us live our life on this planet. I grew up in Slough, which is this small town on the edge of London right next to Heathrow airport; it’s quite an urban area and so I didn’t grow up with nature or natural spaces on my doorstep. I was taught to see nature and feel nature within myself through a very spiritual lens. I grew up as a Hindu and my parents are from East Africa. So that retention of culture and spiritual awareness of nature was quite a large part of my upbringing. As I’ve moved to different places to try to develop my career as an earth scientist, I’ve moved further and further away from who that person was. Because in order to succeed as a scientist you need to be objective and rational and emotionally vacant. There is a part of me that loves that because you’re able to look at science as this process through which you test, observe, measure, evaluate and record in order to progress our understanding of the world around us. For many decades, I loved being in that space, and I still love being in that space.

However, because I was working in a very male-dominated field, a very white-dominated field, I started feeling myself assimilating to the environment around me. And I had to put my true self on a back shelf. There were various experiences that began to really affect my mental health. I physically look different to a lot of the people that work in the earth sciences and the geological field. There’s not very many of us and that sense of assimilation also brings a huge degree of isolation.

I joined a walking group called Dadimas and the lady who set it up, Dr. Geeta Ludhra, invited me along. The group is mostly South Asian ladies from Sikh, Muslim, Hindu backgrounds and some who weren’t religious at all. It was through walking with them in nature and seeing the natural world through their eyes, I began to regain that sense of who I was in terms of my South Asian identity. On one of these walks, a Punjabi woman had returned from India. She said, “As soon as I got off the plane in India, I put my hand to the ground and I felt I was home. I know I wasn’t born in India, but I felt my dharti. I could feel my home through the soil and the rock and my feet on the ground.”

That was such a profound moment for me because I thought to myself, where is my sense of dharti? Where do I call home, how do I ground myself? I do a lot of coastal path walks in Dorset; I’ve just been out to Old Harry Rocks this afternoon, and I thought, that’s my dharti, that’s where I feel that sense of belonging and connection. It’s on the rocks of the Jurassic Coast.

The whole book came about because I thought, other people must feel like me, they must want to know about the world beneath their feet and the world that surrounds them, these rocks that are such silent bystanders to our lives. Perhaps they want to know about why they exist, what their stories are, and how they can find a sense of connection to who they are inside, but also where they fit in the landscape.

You start with Stonehenge, which is very iconic and most people probably know it. How did you decide to begin there?

I decided to open the book with Stonehenge because my initial idea was a complete failure. And I remember talking to my editor on the Monday before the summer solstice, which was on a Friday. I was saying, “This first chapter does not feel right, it doesn’t feel like I’m opening it in a way that brings a sense of majesty to the story I want to tell.” And then I was watching the news and they were talking about the preparations that English Heritage and the National Trust were doing at Stonehenge to get ready for the solstice celebrations and I thought, “That’s it!” I literally live 45 minutes from Stonehenge and I thought, I’m going to go there on Friday. I’m going to see how it feels to be amongst some of the most revered standing stones in the world. What does that feel like? How do other people feel about it?

The whole positioning of Stonehenge was that I wanted to give the reader a sense of comfort and safety in my hands. I wanted the reader to understand that wherever you come from, however you feel about landscape or rocks or geology or even standing stones, you are welcome in this space with me as a scientist because I understand and respect your point of view. Stonehenge became this really powerful piece at the beginning of the book that equitably laid us all alongside each other; everybody’s viewpoint is valid, no matter who you are or where you come from. I come from it from a scientific point of view, obviously, but I completely understand and respect that indigenous peoples all over the world have their own belief systems about rock and landscape. And that’s why I opened it like that.

It feels like there’s a strong emotional connection that the voice of the rock is coming from this place of intense feeling. How do you think people can develop relationships with rocks and the land that they are on? Do they need to know all the scientific knowledge or the more traditional indigenous knowledge to really appreciate and make those connections?

I think, actually, you don’t need to know anything. I think what you do need is to put your hand on the rock and to feel it and to look at its texture and its color and consider the way it makes you feel inside. That is perhaps the most important source of knowledge. If I put my hand on this slate or this sandstone or on the granite that’s in the wall of this building, how does it make me feel? How do I feel when I look at its patterns and its colors and its textures? Does it give me a sense of awe and wonder?

I was in Liverpool a month ago to do an event there and many of the rocks around Liverpool date back to around 300 million years ago; they’re sandstones. They’re really rich red in color. These sandstones formed in ancient desert seas, called sand seas. I’ve spent a lot of time in deserts and what I particularly love about deserts is when you’re there, you can feel the wind on your cheeks, you can feel it ruffle your hair, you can also see how the sand grains are picked up by the wind and rolled along and bounced along the surface of the sand dunes. If I think about being in Liverpool and I’m putting my hand on that sandstone, it’s got these really interesting colors and patterns. I know that that particular rock was formed in an ancient desert. And when I look at those lines and I put my hand on top of it, what I’m touching is an ancient breath of wind that’s moved those sand grains. I’m thinking about that ancient breath of wind that once moved that sand grain and then I’m feeling the wind on my cheeks and it ruffling my hair and that’s the same wind! The wind hasn’t changed, the wind has always been there, 250 million years ago when it formed that sandstone that my hand is touching to that moment where it’s ruffling my hair, it’s still the same wind. And that connection over deep time is the most extraordinary feeling.

In one chapter you juxtapose a juvenile ichthyosaur vertebra, with the fact that fossil fuels come from living organisms. Even if we know that they’re the remains of living organisms, we divorce ourselves from that knowledge. How would that change our reliance on fossil fuels if we really reckoned with their origin?

It was something that struck me as I was writing that chapter. I was thinking, yes, oil comes from these tiny microorganisms, plankton in ancient seas that existed hundreds of millions of years ago. And when we think about coal being formed from lush tropical jungles, when you begin to put it into the space that this life that once existed, albeit hundreds of millions of years ago, makes our life possible, it kind of gives you a sense of humility that something had to die, it had to transform through heat and pressure into this new mineral resource that we absolutely rely on to make our life possible.

We’re in this because something existed hundreds of millions of years ago to make this possible. I think the minute we start to think about that, then we begin to see the rocks as animate beings. Whether they are a piece of granite or a limestone or a piece of coal. Once we begin to frame them in terms of their origin stories, they gain a voice, don’t they?

I think you feel a sense of heartbreak when you see a creature on the roadside that’s been knocked by a car. But when we hold or see the remains of living creatures in museums from hundreds of millions of years ago, that sense of emotional connection is so distant. What I wanted to do was to frame the story of that vertebra. I gave it a voice to reach across the eons to my own heart as a mother, because the vertebra I found was from a juvenile ichthyosaur. It was only one year old when it died. It was something that I found incredibly moving to write.

I really loved that you’re literally giving us the perspective of different rocks. How did you choose which ones you wanted to give a literal voice to?

In the early editions of the book, in every chapter, the rock had a monologue. The editors felt it was a bit too much and they suggested choosing which ones would have the most resonance with the reader. I wanted to keep the ones that I have an emotional resonance with. The one that I read most when I’m at events is the Shetani Lava flow. I really struggle to read it because every time I’m going through its story, it just really chokes me up. Because it was a moment in my life that I remember as if it were yesterday. I have a photograph, I have a rock, and now I feel like I’ve channeled all of those feelings and memories and emotions into a voice for this wonderful relic of that time that I spent on the lava flows.

I definitely wanted to tell the story of that ichthyosaur vertebra because it was such an intimate experience I had when I found it. My daughter was there, and there was this whole sense of mother and daughter and child. That’s a theme that travels through the book, motherhood. Not just me as a mother, but my own mother and how she’s passing her learning on to me.

There’s a chapter on negative spaces. In Petra and other places, the negative space is beautiful, where there’s been rock carved away to be religious places or towns. But then there are the negative spaces that come with mining. How did you construct a chapter on these two very extreme ends of negative space that can be a beautiful way of respecting the rock and also a very destructive force?

I wanted to explore what we mean by seeing beauty in these negative spaces that quite often are created by nature and how does this contrast with spaces that are deliberately wounded so we can extract what we need to sustain our own lives, and where is that balance? There are spaces in nature where natural forces will winnow out hollows and alcoves into spaces, particularly areas of sandstone or limestone; they are quite often places of spectacular beauty. I wanted to tell the story of spaces of negative beauty, places like Mesa Verde.

And then where I live there are a lot of quarries in the limestone because large areas of Dorset where I live were quarried for limestone, which were then transported to London. I’ve lived for 20 years with lots of wounds in the landscape, but also have watched how nature has begun to recover in those spaces where rock has been extracted. What questions should we be asking about the manner in which those processes of extraction are done? Who does it benefit?

The chapter also treads into cultural objects as well, where I speak about Hoa Hakananai’a in the British Museum. His ancestral home is on Rapa Nui and he is incredibly special because he is constructed and carved from basalt, whereas the majority of the moai on Rapa Nui are carved from lapilli, which is volcanic ash. So he’s a rare ancestor. When you see him at the British Museum, he feels at odds with the entire location because moai were crafted and carved to be within that landscape, to look out across the land as guardians for the indigenous peoples. The beauty he would’ve brought and felt in his native landscape is now gracing the halls of the British Museum. I wanted to comment on negative space in a sense that we, as the British public and all of those people who visit the British Museum, are benefiting from the beauty and eminence that Hoa Hakananai’a brings, but it is at the expense of his ancestors.

I would love to hear about how you tried to weave Indigenous stories alongside the science of the rocks and use them as mirrors for each other.

There were three golden threads in the book. One is science, one is traditional knowledge, and the other is my own personal experience. When you begin to weave all of that together, there has to be an absolute respect not only for the science but for the traditional knowledge. Because I am a non-indigenous person. I am a woman of color, I do have a heritage that has been impacted by colonialism, but I was educated in the west, so I had to be very aware of that immense sense of privilege I had moving into the space to retell indigenous stories.

What I didn’t want to do was place science in this supremacist frame of thinking that actually, science has all the answers. It’s provided us with this incredible knowledge about plate tectonics and earthquakes and why volcanoes erupt, and in the last 200 years amazing advances have been made in how we understand how the earth and planet has evolved. Having said that, that knowledge has always been there within indigenous communities for tens of thousands of years. They didn’t necessarily have a ship that pinged radar down to see the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, but they knew about volcanic eruptions and why they were happening and the impact it had on them as the people.

What I wanted the reader to feel was that we should value all sorts of different ways of knowing our world and how it was created, that one way of knowing isn’t more important than the other, they are equally important.

I think it’s often framed as either/or, you look at the indigenous knowledge and traditions or you look at the Western science, but it feels like a loss to not consider both on equal footing. We should be listening to people who have had millennia-long connections to the spaces that they inhabit.

When the idea for the book came about six years ago, I thought to myself, geology absolutely has a grounding in spiritual communities, but who is going to tell that story? There are far more experts out there in indigenous/traditional knowledge and ecological systems, but in geology? And that was my starting point. I’m going to try and do this and I’m going to try and do it ever so carefully, very respectfully, but also from my own position as somebody who bridges the gap between science and spiritualities. It was very challenging.

Are there any specific places you went or rocks that you encountered along the way of researching your book that were really resonant or exciting?

What I’m holding in my hand is a piece of slate and it’s from North Wales. For this particular trip that I made up to North Wales, I was writing about the slate and how it formed and the colonial history. Penrhyn Slate Quarry was at one time one of the largest quarries in Europe. It’s a massive hole in the ground where the slate has literally been blown out the side of the mountain, but when you walk around the surrounding area, there are these huge spoil tips of slate just discarded. As I was walking along the side of the spoil tips, it was the most remarkable experience. At first I felt a sense of grief and loss. I thought, “This epitomizes our role as a human race: destroy what we can see, pick out what we really want, get rid of all the rest.” I found it an incredibly desolate experience.

But when I scrambled up and was amongst them and just being with them, suddenly the sense I got from them about their story started to shift and change. I began to see moss growing on the side of the rocks. If you know anything about moss and lichen, you know that they digest rocks so they can extract the minerals so they can grow. I started to realize, “They’ve got a new purpose in life. They’re not lost, they’re not desolate, they’re supporting all of this beautiful emerging vegetation which then supports the butterflies and wildlife and birds.” In that moment it was this profound understanding that this is a cycle of life. We have propagated and expedited that cycle by blasting the rock out of the ground and laying it out in spoil tips, but the slate in itself is contributing to a cycle of life.

I went to Haugesund in Norway this time last year and I picked up this beautiful rock here. This is called a green schist; it’s green in color, it’s got a chevron pattern, and it comes from the mineral chlorite. When I was writing that chapter about the formation of the Appalachian Mountains you had continents, Laurentia and Baltica and Avalonia, all moving very very slowly together over the course of about 150 million years. The ocean between them was the Iapetus Ocean.

So this is a silt stone from Cornwall. This is from the Iapetus Ocean. What was happening at the bottom of the Iapetus Ocean was you had silts and clay slowly collecting at the bottom of the seafloor forming this sea rock. As these continents are slowly moving towards each other, they push those seabed sediments up, they transform them under heat and pressure and it forms this beautiful schist here. You can see the micro scale defamation of the rock there. What I’m really holding in my hand is the birth of a mountain. Because as these rocks are crushed and heated and pressurized and pressed, they are buckling up and they are forming immense mountain ranges. And this is just amazing. I have so much love for this rock.

Thank you for those examples because, I think, when you’re framing it in silence vs the birth of the mountain, you viscerally hear and feel the way that would sound, the crumbling, groaning, crushing versus the quiet of sediment settling and hardening over long long long periods of time. It does give the rocks literal voices.

I think what it does is it gives it a sense of context, emotion, feeling, because we can understand what that feels like. I don’t know about you, but sometimes I just want to take myself off somewhere and be in solitude, without my kids. This silt stone represents that. This is what life used to be like, 500 million years ago with clays finely settling on the seabed.

What books did you look to for inspiration? What conversation were you having with the literary world of science writing that integrates indigenous knowledge?

This whole journey started with Braiding Sweetgrass. Robin Wall Kimmerer wrote such an amazing book to connect botany and ecology with traditional knowledge. I also very much looked at other nature writers. Robert Macfarlane’s book Underland was really interesting. He didn’t necessarily talk about the science of geology, but he did talk about what it felt like to be underground. There are moments in that book which terrify me because it makes me feel so claustrophobic. He makes you feel quite powerful emotions about being with him while he goes on that journey. Another book that really taught me how to structure the stories is by Lara Maiklem and it’s called Mudlarking. She’s this brilliant, interesting person who walks along the foreshore of the River Thames at low tide and each chapter is about the different categories of the things that she finds. And finally the last book which I thought was so powerful as a woman writer was Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain. She really lives in the moment of observing nature and natural processes. And not just the living processes of nature—what I love about that book is how she observes the rocks, the mountain and the landscape. She feels it in her heart, in every fiber of her being. And through reading that I knew what I wanted to achieve.

Anjana Khatwa is an award-winning earth scientist, TV presenter, and advocate for diversity in the geosciences and nature. She holds a PhD from the University of Southampton, and she won the Geographical Award from the Royal Geographical Society. She is a presenter for the BBC and other networks. She lives by the Jurassic Coast in Dorset, UK.

Lorraine Boissoneault is a Chicago-based writer who covers science, history, and human rights in her journalism, and explores more fantastical worlds in her fiction. Previously the staff history writer for Smithsonian Magazine, she now writes for a wide number of publications. Her essays and reporting have been published by The New Yorker, The Atlantic, National Geographic, PassBlue, Great Lakes Now, and many others. Her fiction has appeared in The Massachusetts Review and Catapult Magazine. Her first book, The Last Voyageurs, was a finalist for the Chicago Book of the Year Award. Her forthcoming book Body Weather: Notes on Chronic Illness in the Anthropocene won the 2024 Lukas Book-in-Progress Prize and will be published by Beacon Press in April 2026.