by Jael Montellano

Every queer person has a relationship to monster stories. When we’re told we’re freaks, abnormal oddities of society, otherness internalizes. Some of us reclaim our personhood, find other monsters, build a monster family, and make a home. Some of us remain in terror of ourselves and do our best to starve the little beasts, asphyxiate them if we can, even if they remain in the corner of our eye, a flash in the mirror, a tentacle in the shadows.

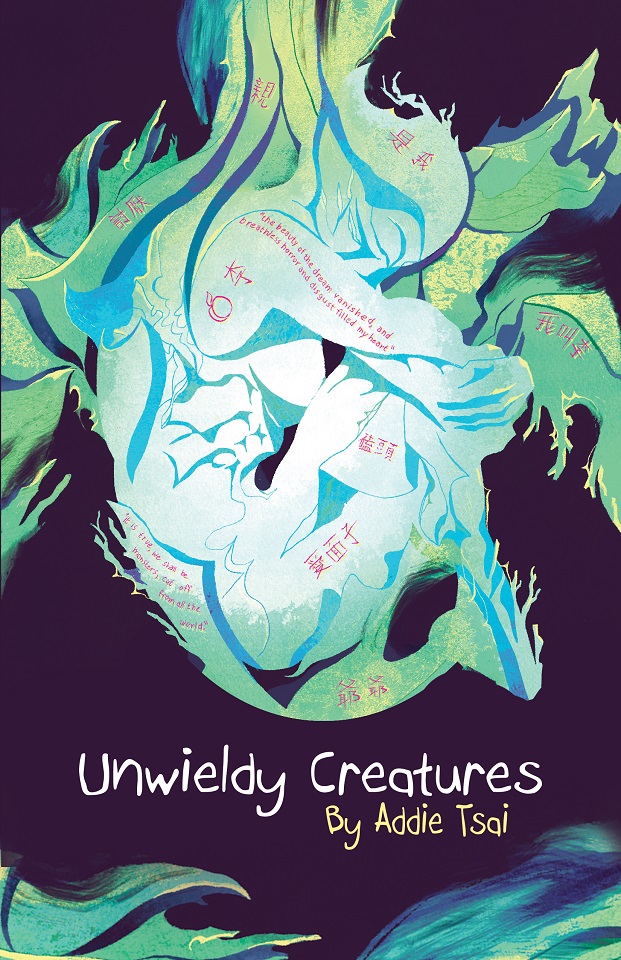

As an endless devourer of monster stories, a way in which I reclaim myself, it was seminal that I correspond with Addie Tsai over her newly debuted Unwieldy Creatures, a novel spun from the original monster literary work Frankenstein, yet revisited from a queer, biracial, nonbinary perspective. In Tsai’s story, we discover Plum, a biracial Chinese intern at Dr. Frank’s embryology lab, Dr. Frank herself, a biracial Indonesian scientist, and her creature, the nonbinary being around whom their tales center.

My conversation with Addie follows.

Shelley’s Frankenstein has the subtitle “The Modern Prometheus,” which alludes to the Greek trickster who created humanity from clay. By the nature of being a retelling of Frankenstein, your novel bears parallel allusions, however, I’d like you to meditate on what it means for you to have used a classic work to tell a queer story in the way Shelley used mythology to tell her own. What place do queer retellings of classical works give us in relation to mythology and owning our histories and spaces?

I love that observation! I grew up, as many of us, learning that I wasn’t the typical person being taught to. Every time my teacher addressed a biblical reference from literature and said, “And of course, we know this comes from the Bible,” and a million other moments that indicated to me that I wasn’t being written to. But, we consume, interpret, and are informed by these texts whether we like it or not. It reminds me of one of my favorite passages of James Baldwin, from his “Autobiographical Notes” at the beginning of Notes of a Native Son:

I know, in any case, that the most crucial time in my own development came when I was forced to recognize that I was a kind of bastard of the West; when I followed the line of my past I did not find myself in Europe but in Africa. And this meant that in some subtle way, in a really profound way, I brought to Shakespeare, Bach, Rembrandt, to the stones of Paris, to the cathedral of Chartres, and to the Empire State Building, a special attitude. These were not really my creations, they did not contain my history; I might search in them in vain forever for any reflection of myself. I was an interloper; this was not my heritage. At the same time I had no other heritage which I could possibly hope to use—I had certainly been unfitted for the jungle or the tribe. I would have to appropriate these white centuries, I would have to make them mine—I would have to keep my special attitude, my special place in this scheme—otherwise I would have no place in any scheme.

It’s important to note, of course, that Baldwin is speaking specifically to the Black American experience; however, this passage was one of the earliest moments of helping me to understand that I could claim the histories and arts we’ve been given by creating a queer potentiality from them. I believe that one way into these works that have excluded us is to use the retelling to speak to the ideologies that are embedded in most classical works and queer them, figuratively and literally, and find the spaces for ourselves in between.

Why Frankenstein? What was your first encounter with this story in your life and how did it impact you? How did retelling it through a queer lens come to be and how does the gothic frame, craft-wise, allow you to tell this three-narrative story in a way that a traditional narrative would not?

I first encountered and read Frankenstein in a Romantics Lit class in college, interestingly, at about the same age Shelley was when she first wrote the novel. Funnily enough, I was sick the day we discussed the novel and my professor asked me to visit him at office hours so he could give me the lecture. This was very early in the days of the Internet and so e-mail was barely being used and course management systems had barely been invented. My professor gave me the lecture in his office. It was in that experience that I deeply connected to the novel as one that helped me make sense of feeling othered and abandoned (like Frankenstein’s Creature), of being a twin (in the ways that Shelley intentionally creates a duality/mirrored existence between Frankenstein and the Creature), and of navigating having a narcissistic father. My professor also discussed how Shelley largely refers to Frankenstein’s creation as the “Creature” until the world turns on him, and it is from that point that Shelley begins to refer to the Creature as the monster, daemon, ogre, etc., now that he has taken on the projections of those around him. I found that fascinating and brilliant. The novel hasn’t let go of me since. A decade ago, I pitched and collaborated on a dance theater adaptation of the novel (as well as the connections I felt the novel held with Shelley’s own life), with Dominic Walsh Dance Theatre, called Victor Frankenstein. I also wrote a nonfiction manuscript about my obsession with the novel and how I felt some of my life experiences connected to the novel as well as Shelley (and her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft)’s life, which hasn’t been accepted by a publisher yet. But, it was a few years ago I began to consider ways to rewrite the novel from a queer and biracial/non-white lens, intersected with my observations around the ethical implications of in vitro fertilization as more and more people were able to access the technologies to start families.

I’ve always been a lover of the epistolary form, since I read The Color Purple in high school, with Frankenstein not far behind. As an identical twin, it’s always made sense to me as a form because I’m always writing to a ‘you,’ which is sometimes specific and sometimes not. But I was also drawn to the gothic frame of Frankenstein for the ways in which it enables a reader to sit with multiple sustained narratives of characters, and give us a multitude of perspectives. I think it would be more difficult to use a traditional framework because it would make it more difficult to really get at the complexities the novel engages with.

As a writer with a bilingual heritage, I long to ask you about language that challenges monolingual readers. Unwieldy Creatures features mixed-race characters of Chinese, Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, and Columbian backgrounds, and therefore you use, particularly, Mandarin characters in Plum’s narrative, with footnoted translations. Why was this choice important to you? Can you tell me about the choice between Mandarin and Pinyin, the romanized spelling that is more often encountered in English works?

Ah!! I’m so excited to have a writer with a bilingual heritage connect with this aspect of the novel. The first thing I have to admit is that I am not fluent in Mandarin. I speak only a few words, can recognize a few more around me. I learned a few characters (and Pinyin) when I took Mandarin in high school, but my understanding is pretty rudimentary. Despite that, and this may be hard to understand, but that multilingual confusion and texture is still a part of how I was formed in the world. I spent my entire life being surrounded by Mandarin, and even though I understood little of it, it still feels like home to me. So, even though this novel is absolutely fiction, there are aspects of how I experienced language in the book. Additionally, Frankenstein is a book about origin stories, particularly when it comes to language and knowledge, and I wanted to bring that aspect into the biracial identities of the characters to the forefront. I chose Pinyin dominantly because Plum is an Americanized biracial Chinese character and felt that made sense for her background. But, I did want the characters to be part of the world of her linguistic identity, which is why I included them in footnotes.

Z, née Zoelle, is Dr. Frank. She identifies as calalai, an Indonesian gender term for masculine women, and yet is unable to recognize the humanity in her queer creation, which she deems a monstrosity, despite sharing a common otherness. Were you concerned about adding to the heteronormative narratives of queer-as-villain, or queer-as-monster? How did you navigate writing Z’s fullness of character, presenting the reality of her childhood trauma, and her subsequent harmful decisions?

Yes! Z was probably the hardest character to write. I wanted to see what would happen if we had Frankenstein as a queer woman; however, I think it is important to the narrative of Frankenstein that Z still can’t get out of her own way, still can’t face her own narcissistic irresponsibility. But, for me, I felt that we get a deeper sense of what has happened in Z’s life to bring her to this end. I also think that we don’t want to get to a place where we only depict queer or non-white characters as heroic. We want our characters to represent the full spectrum of personality and identity and villainy and redemption, because that is the full landscape of human life. Additionally, I wanted to address that so much of who we end up in life has to do with the choices we make with the circumstances we were given. I see Z as a complex figure who is not written in broad trope-y strokes, and I hope others see that, too!

An analysis of colonialism is an analysis of complicated grief. It is haunting, even with emotional distance, to inspect the ways whiteness, privilege, and wealth have harmed POC lives, especially in biracial families like Z’s. Your book is my first encounter with the term “paperwhites,” and I can’t enunciate how accurate this term feels with respect to white fragility and the volatile ways they react when threatened with their apparent diminishing. This is, of course, central to the circumstances surrounding Z’s and Ezra’s childhoods and creates the violence from which the novel’s action springs. How did your personal experience of whiteness inform your crafting of the narrative?

I made that paperwhites term up! I am glad that it resonated. I am a biracial Asian person with a white mother, and I have dealt with whiteness in varying ways personally. When I made a decision to create a queer and biracial retelling of Frankenstein, I also wanted to use whiteness in the book very intentionally, rather than just being the assumptive racial identity, as it is in the original. Although the work is fictional, most of the choices made around whiteness stem from my own experiences with how violent whiteness can be, both quietly and loudly.

Plum is the secondary narrator of the story and provides an illuminatory foil for Z. She fills the role of Robert Walton, the captain that Victor Frankenstein meets in the Arctic and to whom he tells his tale. Walton, however, plays a passive role within Shelley’s original. Why was it crucial for Plum to be an active participant in your tale?

YES! I love this question. When I first read Frankenstein, I was always a bit disappointed that Robert Walton serves such a slim role in the novel, and so I wanted my Walton character to be integrated fully into the novel from the beginning to the end. I also wanted to have her connected to both Frankenstein (Z) and the Creature (Ash) and see her wrestle with all the complexities around both of them. In a sense, Plum represents the reader as they come to terms with how the novel moves through its tensions.

[SPOILERS WITHIN THE FOLLOWING] The denouement of your story differs from Shelley’s original, in which Victor Frankenstein dies and the monster grieves the loss. By the end of Unwieldy Creatures, we do not know the fate of Z, and we have a hopeful turn of events for Ash, instead of the morose suggestion that, alone, the creature will end its days. Why did you make this alternative choice? Is there a message you desire to leave queer readers with?

Absolutely. As we spoke earlier of queer-as-villain and queer-as-monster, it was crucial to me that the Creature did not end up as a queer tragedy. I wanted to end in wholeness for these characters, especially for Ash. This book, unlike Frankenstein, ultimately is a book of love.

Addie Tsai (any/all) is a queer, nonbinary artist and writer of color who teaches courses in literature, creative writing, dance, and humanities in Houston. She teaches in Goddard College’s MFA Program in Interdisciplinary Arts and Regis University’s Mile High MFA Program in Creative Writing. They collaborated with Dominic Walsh Dance Theater on Victor Frankenstein and Camille Claudel, among other productions. She holds an MFA from Warren Wilson College and a PhD in Dance from Texas Woman’s University. Addie is the author of the young adult novel Dear Twin (Metonymy Press). Their writing has been published in Foglifter, VIDA Lit, Banango Street, The Offing, The Collagist, The Feminist Wire, Nat. Brut., and elsewhere. Addie is the Fiction co-Editor and Features & Reviews Editor at Anomaly, contributing staff writer at Spectrum South, and Founding Editor & Editor in Chief at just femme & dandy.

Raised in Mexico City and the Midwest United States, Jael Montellano is a writer and editor based in Chicago. Her fiction, which explores horror and queer life, features in The Selkie, The Columbia Journal, Hypertext Magazine, Camera Obscura Journal, among others. She holds a BA in Fiction Writing from Columbia College Chicago. Find her on Twitter @gathcreator.