by Jael Montellano

When I was eight, I thumbed through a book of poetry in my mother’s library, a compendium of Mexican poetry titled Ómnibus de poesía mexicana (1971) edited by Gabriel Zaid, which infused in me a love of language and compressed forms. I recall still how it was covered in thin plastic to protect its cover, how dust motes danced in the sun’s filtered rays while I sat devouring works by poets such as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, José Hernández Campos, Octavio Paz. Most of all, within the text, I was fascinated with an eighteenth-century riddle that went:

“Dos hermanas diligentes

que caminan a compás,

con el pico por delante

y los ojos por detrás.” (Zaid, p.127)

I was as flummoxed by its anonymous origin as I was by my inability to solve it (I’ll let you hazard a guess at its answer. If you give up, scroll to my bio). Years later, it became for me a symbol of my cross-national duality, equal parts cultural amputee and clever survivor at once, a tragedy other bilingual writers will recognize, and which is oft repeated in the problem of translated works.

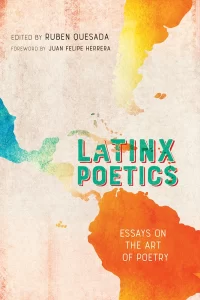

Ruben Quesada’s new anthology, Latinx Poetics: Essays on the Art of Poetry (University of New Mexico Press, 2022), curates writing from across the wide family of “Latino, Latin American, Latinx, and Luso poets about the nature of poetry and its practice.” It also probes a poet’s anatomy of language, translation, history, tradition, and by extension, latinidad’s complex identity, with the purpose of expanding and enriching our humanist borderlines.

My exchange with Ruben about the dazzling iridescence of this anthology follows.

How do you define Latinx poetics? When you picture this collection’s readers, who are they?

When I think of any poetics, I turn to the word’s meaning. Poetics deals with the techniques of poetry. We admire writing that employs narrative, rhythm, and sound, alone or in any combination. These elements make up the style, but we must interrogate a writer to know its nature. There is always an implied speaker in a poem, a form of rhetoric. Rhetoric is the art of using language effectively. In recent years, we’ve come to understand forms of communication may not be honest or have our best interests in mind. It’s rhetoric. I want to know what compels a speaker or writer to compose. The language of these writers is inseparable from Latin America. As I know myself more deeply, my understanding of language evolves. This book expands our understanding of writing and composition. Someone interested in people and the humanities will find something valuable in this book.

How did editing this collection come about for you? Describe your editing journey and process.

The origins of this anthology project began in the late 1990s. I was an undergraduate studying poetry at Riverside, and that year we had two visiting poets. They were the first poets who looked like people in my family–uncles and aunts. Poets like Carmen Giménez, Valerie Martínez, and Norma Cantú. These poets gave me the confidence to be a poet, critic, and activist.

In the early 2000s, when I was at UC Riverside, I imagined an anthology like Dana Gioia’s Twentieth-Century American Poetics (2004), collecting writing from Latinx poets at various stages of their careers. “So Much Depends” by Julia Alvarez in Twentieth-Century American Poetics describes how she discovered William Carlos Williams’ language and rhythm by connecting to his use of syntax like her native Spanish. Alvarez reminds us that by “writing powerfully about our Latino culture, we are forging a tradition and creating a literature that will widen and enrich the existing canon. So much depends upon our feeling that we have a right and responsibility to do this.” Alvarez admits that when she was younger, she “was embarrassed by the ethnicity that rendered [her] colorful and an object of” cultural performance. Alvarez’s life experience was not in the literature. She sought stories that reflected experiences like her own. Though there will always be change and more to recognize and include, we live in a world of seemingly infinitesimal data.

I’d secured most of all contributions by the end of 2017. I spent the next two years focused on completing the project with the help I received from my editor Elise McHugh and poet Natalie Scenters-Zapico. They helped me copy-edit, and they helped me respond to and communicate with contributors. I completed the anthology in the years of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, 2019 – 2021.

By definition, ethnicity contains markers of sameness and commonalities such as tradition, language, and culture. How do you collect a record of something meant to represent sameness but also ensure a diversity of voices representative of the Latinx diaspora? What challenges did you encounter?

A poet’s tool is language. Sometimes we invent words. Words like snark, mimsy, and chortle. The ancient word for a maker or an author can be traced back to Sanskrit as cinute. It means to arrange or collect or put in an order. When I started putting the proposal for this book together, I turned to poets I knew to ask if they’d consider writing something in prose about their poetry and its composition. Not every poet writes essays or long-form prose. Some had to be convinced, some weren’t available, and others were eager to contribute. It would take volumes to include anything close to being representative of the diversity of the Latinx diaspora, and that diversity will continue to evolve. If it didn’t, we’d be amid some kind of apocalyptic, eugenic mandate. This branch of knowledge, like any other, builds upon what is known.

There are many different ways to put together an anthology. I survey recent poetry anthologies in my “Introduction” to this anthology. Over the past two decades, a widening interest in Latinx poetry has created a need for anthologies. Some of my favorite collections are:

Contemporary Costa Rican Poetry (2012), edited by Carlos F. Monge & Victor S. Drescher;

Latinx Comic Book Storytelling (2016), edited by Frederick Luis Aldama;

!Manteca! An Anthology of Afro-Latin@ Poets (2017), edited by Melissa Castillo-Garsow;

Nepantla: An Anthology for Queer Poets of Color (2018), edited by Christopher Soto.

Different challenges required thought and examination, some beyond my control. Putting this book together took dozens of people. The book itself had a page count limit and a budget to follow. Like all projects involving people, there are time, money, and labor challenges.

The essays within this collection span a myriad of subjects; language and form, identity, religion, sexuality, trauma, collaborative art, activism, etc. By which criteria did you amass these astounding literary voices and texts? Do you have a favorite?

As you’ve noted, this anthology collects writing from writers with varied experiences and perspectives. My criteria come from a place of curiosity. I spent the last two decades studying and teaching poetry. I don’t ever feel like I’ve learned enough; there’s always something new to discover in poetry.

An essay that resonates most with me is Blas Falconer’s “Puerto Rican Poetry and / a State of Independence.” The piece introduces me to the relationship between Falconer and his grandmother and a poetic form called the plena, or the periodic canto. The poems in Yerba Buena by Puerto Rican activist Juan Antonio Corretjer (1908-1985) are “a patriotic symbol.” Like Julia Alvarez, here was a moment of discovery about a people’s history and literature. Falconer documents the past, offering reader insight into social and historical subjects.

What do you feel American publishers have failed to do when presenting works of latinidad to a larger audience? What do you think this collection succeeds in doing differently?

New forms of writing highlight untold pasts of life in the United States. Recent poetry about language and history has expanded our imagination of historically resilient communities. Pulitzer Prize finalist Mai Der Vang’s Yellow Rain (2021), National Book Award finalist Anthony Cody’s Borderland Apocrypha (2020), and this year’s banana [] by Paul Hlava Ceballos. Their techno-poems are an interactive space for deep engagement by deconstructing sentences and historical information and incorporating technology to understand its meaning.

Poetry can explain something about the world and mesmerize us. Poetry and the poet’s relationship to language have always interested me. As a Spanish heritage speaker, I’ve always had a circuitous relationship with language. I’m reminded of Robert Pinsky, whose prolific writing on poetry is fundamental to our understanding of American poetry. The Situation of Poetry (1977) is about words and their relationship to experience. Pinsky traces early American poetry to his timeline. This anthology tries to answer comparable questions from many perspectives. How can a poet hold an experience with language? And how do we communicate the human condition across culture, language, and time?

Every essay is different, offering a glimpse into the minds of working poets in the early 21st century. This book is one-of-a-kind. The contributors come from all walks of life. I hope readers find it valuable and inspiring.

In her essay “Peopleness–Ethnicity and the Latino/a Poem,” Valerie Martínez notes writers “might ask how [their] work performs latinidad” and whether “they have an obligation to signal ethnicity.” How does this collection perform latinidad? What is its obligation?

The more we know about others, the better we understand one another. It’s natural to misunderstand or be afraid of the unknown. But history has shown us that when we welcome those who are unlike us, we’re better for it. In Julia Alvarez’s essay, she writes, “I was embarrassed by the ethnicity that rendered me colorful and an object of derision” in the literary community, “at least not without paying the dues of becoming like them” (Gioia, p. 434). Alvarez was encouraged to assimilate.

Before the 1980s, Alvarez found books by Latino men in bookstores and libraries, but she “could not find any women among these early Latino writers.” Knowing that someone from your heritage has contributed to your community matters, but there’s more to us. Alvarez explains how she discovered her way into a bicultural, bilingual experience by reading Asian American writer Maxine Hong Kingston. Kingston wrote about the duality of experience and its pressure on being a Chinese American female.

It’s troubling to expect a writer to perform their cultural identity, and wearing it on your sleeve shouldn’t be detrimental to the work. Of course, I felt obliged to include as many different perspectives and backgrounds as many different connections to Latin America. As long as I can remember, it has always been important to me to be inclusive. I wanted contributions to my anthology to include historically marginalized identities, and sometimes those identities exist beyond academic and cultural spaces. There’s much to learn about the people of the Americas through Latinx literature.

Brenda Cárdenas makes the glorious point in her essay, “Poetry in Concert with the Visual Arts: Latina/o Ekphrasis and Other Fusions,” that there is the paradoxical inclination of bilingual forms to “simultaneously celebrate and shield” Latinx to “gain visibility without fully exposing them and relinquishing their secrets to the colonizing gaze that would exploit and erase them.” How do we, publishers, and cultural leaders, straddle this paradox? How do we grow Latinx visibility while protecting it from the colonial eye and keeping our golden truths for ourselves?

It’s an honor to have the University of New Mexico Press take on this project. UNM Press introduced me to poets like Paula Gunn Allen, Gabriela Mistral, and many more writers of Latin American and Indigenous heritage. Just as they’d done, I wanted to introduce poets of Latin American heritage to all types of readers.

Physician and award-winning poet Rafael Campo shares in his essay, “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off, Or the Possibilities of a Contemporary US Latin@ Poetry,” about an experience in 2007 when he wrote a 3000-word book review on Latinx poetry. By this time, Campo’s four poetry collections had been honored by the National Book Critics Circle, Lambda Literary, and the National Poetry Series. The review was never accepted for publication.

That same year, Rigoberto Gonzalez published an article titled “Those Pesky Minority Poets,” where he traces resignations from the Poetry Society of America and the Academy of American Poetry. He admits, “I do agree that talent is color-blind, but I do know for a fact that I’m not, and neither is anyone else.”

Latinx writers are Black, Indigenous, Asian, White, and more. We do not find ourselves in every color in publishing. For most of the twentieth century, we didn’t find ourselves published anywhere. Giving people unlike you more visibility and inclusion creates a greater sense of belonging for everyone. When a publisher embraces the unknown, it offers readers a path to navigate new terrain. In the early 2000s, over 35 million (12%) Hispanic people were living in the U.S.¹ Today, more than 60 million², about 20% of the U.S. population. It matters to be seen and recognized, but any publication’s visibility relies on marketing and promotion. That’s a publishing area where more pressure must be applied to achieve equity.

As challenging as some of the essays are, in context and subject, there is a joy to be found within the exploration of poetics through the eyes of poets. Steven Cordova writes, “it’s a kind of ecstasy; to control the form at the same time that it–the form–controls you.” Francisco Aragón takes us through his thought association process while composing a poem, both different in form and content. With these in mind, what overriding thoughts do you hope to leave readers concerning Latinx poetry?

When a poet writes prose, it also reveals something about them. As I must echo your response, what comes to mind is a form of queer joy. They have diverse backgrounds. Steven Cordova is from Texas, where he studied, but he’s been a poet and activist in New York City since the 1980s. Francisco Aragón is a professor from San Francisco; he studied writing and literature at elite institutions around the country during the 1980s and 90s. These are two queer poets of our time who have striking differences. These distinct voices from varied backgrounds are a form of inclusion and an expansive way of exploring poetics and writing composition.

When considering the inspiration for a poem, Francisco Aragón remembers sitting on a balcony the summer after graduating from UC Berkeley at a friend’s beachfront apartment in France. He listens to the sound of the sea and the breeze. He concludes that it “wasn’t enough to be a catalyst for a complete poem. Which is not to say that it wasn’t deposited into my memory bank. It most certainly was” (Quesada, p. 42). In contrast, Steven Cordova’s essay is a series of declarative statements; he opens, “once upon a time, I was politically active, very politically active, then I burned out…I’m happy to lead a life of reading and writing. I mean I have a TV, but I don’t watch TV, don’t watch the news” (Quesada, p. 58). The essays I collected take on many styles that will appeal to readers, writers, and teachers of all kinds.

To put it succinctly, I want the book to inspire others to explore the nature of poetry further. The way that Dana Gioia’s collection of 20th-century essays on poetry, published almost 20 years ago, inspired me to put this book together.

¹ Guzmán, B. (2001, May). The Hispanic population 2000 – census.gov. The Hispanic Population: Census 2000 Brief. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/2000/briefs/c2kbr01-03.pdf

² U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. (2022, September 26). Office of Minority Health. Profile: Hispanic/Latino Americans. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=64#:~:text=According%20to%202020%20Census%20data,group%20after%20non%2DHispanic%20whites

Ruben Quesada is the author Latinx Poetics: Essays on the Art of Poetry (November, 2022; University of New Mexico Press), and the author of Revelations (2018), Next Extinct Mammal (2011), and translator of Selected Translations of Luis Cernuda (2008). Quesada has served as an editor for AGNI, Pleiades, and The Kenyon Review. His writing appears in Best American Poetry, Ploughshares, Guernica, and Harvard Review. He has been honored by the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events in the City of Chicago, Canto Mundo, Lambda Literary Writers’ Retreat, Napa Valley Writers Conference, and Vermont Studio Center. Quesada has taught courses on poetry and poetics for Vermont College of Fine Arts, Northwestern University, Chicago High School for the Arts, School of the Art Institute, Columbia College Chicago, and University of California, Riverside. He is an Associate Teaching Fellow at The Attic Institute and teaches for the UCLA Writers’ Program. He lives in Chicago and serves on the board of the National Book Critics Circle.

Latinx Poetics collects personal and academic writing from Latino, Latin American, Latinx, and Luso poets about the nature of poetry and its practice. At the heart of this anthology lies the intersection of history, language, and the human experience. The collection explores the ways in which a people’s history and language are vital to the development of a poet’s imagination and insists that the meaning and value of poetry are necessary to understand the history and future of a people. The Latinx community is not a monolith, and accordingly, the poets assembled here vary in style, language, and nationality. The pieces selected reveal the depth of existing verse and scholarship by poets and scholars including Brenda Cárdenas, Daniel Borzutzky, Orlando Menes, and many others, with a foreword by former U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera.

The essays not only expand the poetic landscape but extend Latinx and Latin American linguistic and geographical boundaries. Writers, readers, educators, and students will find awareness, purpose, and inspiration in this one-of-a-kind anthology.

Raised in Mexico City and the Midwest United States, Jael Montellano is a writer and editor currently based in Chicago. Her work, which explores horror and queer life, features or is forthcoming in Fauxmoir, The Selkie, the Columbia Journal, Hypertext Magazine, Camera Obscura Journal, among others. She dabbles in photography, travel, and is learning Mandarin. Find her on Twitter @gathcreator. ✂️