Interviewed by Christine Rice

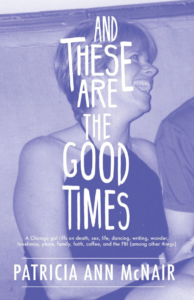

Patricia Ann McNair’s essay collection And These Are The Good Times, out now from Side Street Press, is equal parts:

…death, sex, life, dancing, writing, wonder, loneliness, place, family, faith, coffee, and the FBI (among other things)…

‘Among other things’ is where these essays live. McNair’s generous and expansive gaze connects subjects that–in a time when divisiveness threatens to upend us–cross culture, race, and gender including travel, friendship, mothers, fathers, bullies, bars, siblings, breakups, teeth, fear, bravery, virginity, illness, running, story, sexual abuse, running, love, regret.

Among other things.

In the tradition of the best essayists, McNair’s writing is marked by an honest vulnerability. She’s writing into the discovery (think George Orwell, think Virginia Woolf, think Gretel Ehrlich, think James Baldwin) instead of writing to a predetermined end. She’s on a quest, a personal journey, always a personal journey, when she steps back to take in the landscape where those hard-to-pin-down universal truths reside. Through McNair’s thoroughly modern lens, the universals seem at once fresh and familiar: our hunger for love, peace, a good meal, a cool drink.

Below, Patty and I discuss the messiness of writing memoir, teaching, running, and Gabriel Garcia Márquez, in no particular order…among other things.

CHRISTINE RICE: E. M. Forster is famously quoted for writing:

“How do I know what I think until I see what I say?”

After finishing And These Are The Good Times, I wondered about your process of writing into an essay, getting into all of that messiness. Do you approach essays differently than fiction? From travel writing? If so, in what ways? And where are the intersections?

PATRICIA ANN McNAIR: I love the word messiness in this question, Chris. Because that is what essay writing–or brief memoir, or creative nonfiction—is for me. Messy. Very, very messy. And since you ask, I would have to say that my fiction process is not exactly tidy, but my nonfiction is akin to hoarding. I gather and I gather and I gather. I use my journal a lot in this process (I do keep an almost daily journal practice), write things out. Like questions I have been mulling: What happens when I get to be my dad’s age when he died? Is it all right to have regrets and feel guilt about things I couldn’t really control? Can you not understand another language and yet understand a story told in it? Why? How? What if? Or I explore something I have seen: an apparent break up in a restaurant, a parent letting his child run around loose inside a carnival ride carriage. Or I just start to think about “like” things: coffee dates, running paths, sex and death, jukeboxes. And I write without any real destination, and not always even with an idea that I am going to make an essay. But patterns emerge—like we teach our students at Columbia College Chicago to look for, the obvious patterns and the weirder, abstract ones. And then the essay begins to take shape. I never really know what it will be about until I have written it for a while, lived with it on the pages of my journal and in the guts of my computer. (Confession: sometimes I never fully understand what my essays are about, but I still feel a doneness to them.) I might at first think “Oh, this is about the places where I have run in the world.” And that will be enough to get me going, to write a few instances or episodes, but it is in the accumulation of these bits, it is in the hoarding that I begin to understand what the piece wants to be about—not running, but writing. Not coffee, but grief. Not loss, but finding a comfort in loneliness.

And this sort of hoarding of narrative possibilities and ideas is part of my process in fiction, too, although the big difference there is that I get to creating scene quickly and always first, and then the “aboutness” of the story emerges from the physicality of it. In my fiction there is a sort of numeracy, I think. Things tend to “add up” in a way my nonfiction doesn’t. Meaning, quite literally, that I make fiction through a series of acts (“this happens, then this happens, then this happens, then this”) that, while not always chronological, the acts tend to be kind of logical, a sort of summing up of parts to make a whole. Often my journal fills with a type of writing that is more interior as a starting point, and this is more likely to lead me to nonfiction or essay. And then I find the connections to the things I observe, the dramatic moments I remember, and weave these together in no obvious (at first) order.

My travel writing, the stuff I do for pay, is neither of these. It is very organized and aimed toward destination, a particular destination that I have been hired to write about. And so, to my mind, not nearly as interesting as this other, messier work.

CR: Yeah. Travel writing is, after all, journalism and requires a certain structure.

When I teach a creative nonfiction/memoir class, this is the quote I write on the board at the beginning of the semester:

What matters in life is not what happens to you but what you remember and how you remember it.― Gabriel García Márquez

So, basically, Marquez is saying that memory is a slippery thing. That writers, sometimes, are unable to perfectly fit events into the confines of narrative. In “What You’ll Remember,” for example, there is a gauzy effect that happens by choosing a second-person address, like these things may have or may not have happened (which I really loved).

And you use that dream-like quality, that suspension, in your fiction too.

Do you feel like you fall into Marquez’s camp on this point? And what does that say about the reader/writer relationship?

PM: Oh yes, I am definitely pitching my tent with Marquez. And it is interesting to be thinking about this right now, because as the book release party nears, I have discovered that a few of my friends from a long time ago—high school and earlier—who are in the lines of some of these pieces, who were there for the “good times” I talk about, have started to chat on Facebook about the book and about coming to the release. These are not people I really know much anymore, but they were definitely very important to me early in my life, they are part of what and who I have become. And I realize that even though I have changed names and made some composites and remember things in ways that are likely not accurate to the actual events of our past, some of the what and how of my memories may affect these readers in ways I have not considered before. And so I am now thinking about how I can make it clear to those readers, those participant observers from my past, that the things I tell they should not take personally, this isn’t really about them at all, but about me, about how I grappled with what I observed and I remember and the bits of imagination I use to fill in the spaces around memory and experience.

PM: Oh yes, I am definitely pitching my tent with Marquez. And it is interesting to be thinking about this right now, because as the book release party nears, I have discovered that a few of my friends from a long time ago—high school and earlier—who are in the lines of some of these pieces, who were there for the “good times” I talk about, have started to chat on Facebook about the book and about coming to the release. These are not people I really know much anymore, but they were definitely very important to me early in my life, they are part of what and who I have become. And I realize that even though I have changed names and made some composites and remember things in ways that are likely not accurate to the actual events of our past, some of the what and how of my memories may affect these readers in ways I have not considered before. And so I am now thinking about how I can make it clear to those readers, those participant observers from my past, that the things I tell they should not take personally, this isn’t really about them at all, but about me, about how I grappled with what I observed and I remember and the bits of imagination I use to fill in the spaces around memory and experience.

And here is another quote, this one from Isabel Allende, I think:

“A memoir is my version of events. My perspective. I choose what to tell and what to omit. I choose the adjectives to describe a situation, and in that sense, I’m creating a form of fiction.”

As a fiction writer, a storyteller, I like this idea. It appeals to me and is likely about as close to what I am doing as anything. I am creating a new narrative, fiction or non. I understand that not all readers (or even all writers, for that matter) are going to buy this idea, and that is why I often will say directly in my nonfiction: “I don’t remember this part, but I imagine…” Or, in the case of the piece you mention, “What You’ll Remember,” I flat out say how I would prefer to remember what happened compared to what (I think) did happen. Funny, in real life, we would be forgiven these impulses to exaggerate, to make an easy sense of things, to get the true stories told over the family dinner table wrong to meet our own purposes. I am hoping that readers of nonfiction allow that same sort of latitude to the writers of nonfiction.

CR: There is also this question of having the time and distance (narrative distance) to actually make sense of what has happened, to connect the dots, to see patterns.

Patterns are particularly important in essay work, throughout this book. And it’s kind of magical, in that it takes a hell of a lot of hard prep work to get to that magic, when an essay starts to come together.

Can you talk about the identification of patterns, how that happens for you? I know that you are an advocate of the writers’ journal.

PM: I talked about this some in answer to your first question, but I think it is worth repeating that allowing patterns to emerge from things, to write with an intention of discovery and not simply as proof of what we already know, can lead a writer to the most compelling material. I am thinking about your book, Chris, Swarm Theory, and how there were a number of things that recurred or created a sense of motif, (cars, bees, infidelity, daughterhood, loss,) and how the title of the book, and the title story Swarm Theory, so beautifully gets to the heart of this connecting the dots, identifying patterns. My journal, as I’ve said, is where I gather things, where (I’m gonna steal from you now) I start to understand what these swarming things tell me.

I also consider the journal as a place to do a sort of mindful meandering. Meaning I use it for wordplay, list-making, scribble drawing, and sometimes this activity called blind contour drawing that my husband, the artist Philip Hartigan, taught me how to do. You draw something by keeping your eye on it while you draw, and don’t look at what your hand is doing or what your drawing looks like until you stop making this extended mark. It is really cool, very frustrating, quite Zen. Philip calls it “yoga for the writer’s mind.” It inspires a sort of mid-distance stare and body rhythm that lets your mind work without you forcing things. I can’t quite explain it; you just have to try it.

I also encourage any journal keeper to look back over her journals every so often; it will be clear pretty quickly what sorts of things take the journal keeper’s attention. The patterns will lift from the page, as will how the narrative distance affects what we tell and how we tell it and what the hell it all might mean.

CR: Fortunately for me, a few of these essays appeared in Hypertext Magazine – in print and online. “There is a Light That Never Goes Out,” “I Am Not Afraid,” and “Roger the Dodger” appeared online, “Dentist Day” appeared in our print edition Hypertext Review.

Chicago really seems to support its own. We always had a sense of community through Columbia College Chicago too.

What would you say to writers just starting out? I mean, I always thought that I didn’t need a community of writers, always felt, somehow, outside of it. Until I didn’t. How important is community to a writer?

PM: I am one of those people who really, really, loves to be alone. I like to feel lonely, especially when I am working on a story or an essay. It forces me to talk to myself, to answer myself. And there is a sort of forced responsibility in that act. People, like all of the other things we surround ourselves with—screens, phones, internet, movies, the daily horrors of the news—can be a distraction. BUT, and this is a loud BUT, if a writer spends too much time alone, there is a danger that the writing might become nothing more than muttering to herself. I guess what I am talking about here is partly audience.

My students often say that they write only for themselves and when they do and I read their work, I think one of two things. Either, 1.) you really need to think about writing for someone else, think about the way a reader will engage with this, think about what you owe them in terms of clarity, etc. Or, 2.) Bullshit. That “bullshit” comes from seeing in their work a liveliness or attentiveness that invites a reader to read on, that feels like the writer is sharing something with the reader. And this kind of lively, inviting work usually comes from some awareness that others will be reading these words, that the writer is striving to connect.

So audience as community is one thing. You mention that Chicago is such a lively lit hub, and I could not agree more. There are so many writers here, so many readers, and so many opportunities to come together. Writing, the actual, physical process of it, can be very isolating, very lonely—in good and not so good ways. To be able to be part of the literary community of Chicago is incredibly rewarding. The bookstores that care about books, not just sales; the live lit scene; the journals (like yours) that are publishing exciting work; the writers I know from Columbia College Chicago and just from around town—well, I cannot imagine a more communal and welcoming place to be a writer.

See, here’s a thing that a writing community can give a writer: understanding. Meaning, there are few other places where we writers can say things to one another like: “That would make a great title.” “Have you written that yet?” “I got 500 words today.” “How’s the book going?” And every writer you say these things to understands what you are really saying: “I’m a writer. I’m a writer. I’m a writer. And so are you. Cool.”

CR: One of the essays in this collection, “A Storied Life,” is about as good of an essay about ‘process’ as I’ve read. Recently, two very important people in the writing community, to you and to me, died: John Schultz and Betty Shiflett. They had an unorthodox approach and saw writerly sensibilities in working-class people. They opened up the definition of ‘who can be a writer’ in many ways and for many people.

Can you talk about their influence on your writing, on you becoming a writer?

PM: Oh, thanks for that Chris. I’m glad you liked that piece.

I recently said to someone that if it wasn’t John or Betty who taught me what I know about writing, about teaching, then it was someone they taught who did. I come from a family of writers, but even so, it wasn’t until I got to Columbia College Chicago, to the then Fiction Writing Department, to classes that used the Story Workshop approach to the teaching of writing (John Schultz’s pedagogical invention) that I began to understand that good writing was more than just pretty words put into pretty sentences. They (and the teachers they educated) taught me what it means to make story, and how story can hold so very much.

When my short story collection, The Temple of Air, came out in 2011, I was surprised at how many people expressed appreciation for the attention to detail, to sensory perception, to voice, to a willingness to work with uncomfortable content. I thought, isn’t that what writers do? And then I realized that no, not all writers do what we were taught to do in our Story Workshop classes. Those quiet coachings that Betty and John would give from the sidelines, I hear them still whenever I write. See it. Tell it. Listen to your voice as you tell it. Tell it so that all of us can see it as well. What happens next? They put a high demand on our writing, on our stories, on our teaching. And even though they influenced so many writers, so many writing teachers, their absence still leaves a rather gaping void.

CR: It always makes me happy to find writers whose writing is darker than mine.

PM: Cool. I am honored. The darkness becomes us.

CR: In “We Are All Just Stupid People,” you write:

These are the moments I want to tell, to write, the ones that leave me a little raw, that hold love and loneliness and memory and pain and suffering and survival. “Beauty is created out of the labor of human hands and minds. It is to be found, precarious, at some tense edge where symmetry and asymmetry, simplicity and complexity, order and chaos, contend,” the chemist and poet Roald Hoffman wrote.

You began the essay with a quote from a member of a book club who said:

Your characters are so stupid.

And you talk about reading Raymond Carver’s “The Bath” and thinking (or saying),

“You can do that?”

What I meant: You can write a story that ends in such a tragic and bleak way that it hurts like looking at something too shiny, too beautiful, and still make your reader come back for more?

And then there’s the essay, “My First Bully,” where a schoolyard bully from your adolescence connects with you to tell you that she knows about your book, that she’s found you.

So I’m wondering: why not just write these essays and stuff them in a drawer? Forego the pain of discovery, of someone trying to correct your account of events?

Especially with personal essays, people think that, after reading something about you, they know you in some deeper and more personal way.

How do you resolve that opening up of yourself as a writer? Does it make you uncomfortable at all? Is it true: do they know you on some deeper level?

PM: I suppose in some way we write because we want to be known better, is that true? If not known better by our readers, then at least by ourselves—going back to your first quote from Forster.

So the essay “Roger the Dodger,” about my brother and our relationship and the end of his life and my regrets, I had been carrying around with me for a long time. What I mean: I had these experiences I wrote about in the piece, and I knew that I wanted to examine them more deeply; I wanted to examine my guilt, my love, the marginal life that Roger led, his unbound love of that same life. I went at it a few times. Lots and lots of writing in the journal. A fictional start about a Chicago cab driver. False starts on the essay. And then I had this opportunity to submit this collection to a Chicago publisher (Side Street Press), and it wasn’t yet done, and I knew that what I needed to do was to tackle that essay. And so I did. I wrote and I wrote and I wrote. It turned out to be shorter than I imagined (and that probably means I have more to write, another essay perhaps, that short story, maybe) but it felt done. And, exhausted, I went to lie down to take a nap. And then the room started to spin, I couldn’t lift my head, I was shaking all over. I threw up. Philip came home and I said “I think I am having a heart attack, I need an ambulance.” So we called one. And they came and wheeled me out and I threw up again. Twice more. All over the EMTs, splashing onto the steel walls of the ambulance. They took me to the hospital where Roger died, where I and my other two brothers sat with him when he stopped breathing. “Ok,” I thought, “all right, I need to revisit this place.”

It wasn’t a heart attack. What was it? Probably just a bug. Or probably, more likely to my mind, the necessary and painful release of what I had been carrying with me for a few years.

Does it make me uncomfortable? It makes me throw up. Would it be better to carry this around, keep it to myself, or to hide it in a drawer? I don’t think so. I think light is important, turn the light on it, look at it. This way, now this. Do you (me, the writer, you, the reader) understand things now? Do they (my readers) know me on some deeper level? Maybe. But frankly I feel more exposed by my Facebook posts and how everyone knows I have recently moved, that my cat is sick, that I am on a diet.

I always cringe when writers say they write because they must. And yet, there is this: a reader does not have to read these things. Me, though? I think I might have to write them.

Why do we do it? Damn good question. Why do you think we do?

CR: Oh my…now I’m kicking myself for asking that question… It’s true, though. Facebook does reveal startlingly huge amounts of information, information my parents would have never considered sharing.

My Mom always says, “What’s it to you?” In other words, “Why do you need to know? Are you just being nosy?” Yeah. I guess I am being nosy. What’s it to me? EVERYTHING! Why do people act they way they do? I want to figure it out. Personal essays are really the predecessors to the Enquirer and People and reality television. They’re high art but, when you get right down to it, memoirs and personal essays give readers a way to connect on so many different levels. I mean, when I read a good personal essay, I feel less alone.

Thanks for asking…

There has always been a deep connection between writing and travel. Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Virginia Woolf, to name a few, relied on that jolt of unfamiliarity to see things in new ways. “Your Comfortable Shopping” (among other essays) deals with travel.

Your mother was a travel writer. You are a travel writer. What a wonderful gift from your mother.

Can you talk a little bit more about that connection? Did she also want to write fiction? Essays?

PM: My mother wrote a science fiction story that was published in the 50s. It was a thinly veiled commentary on McCarthyism. She and my dad were Communists; they have FBI files. As far as I know, that was the only fiction she ever wrote, and I would bet she would say it wasn’t all that fictional.

She did write the occasional essay, but they weren’t published. She liked travel writing. It could allow her the chance to be both organized, precise (two things she was quite good at,) but also creative, imaginative. She wrote travel pieces and geography books, and always with the intent of making people want to visit the places she wrote about. She was born in Korea (her parents were missionaries) and lived in Japan as a toddler. She had a desire to explore, influenced by the adventures of her early life. She used to talk about how she loved the smell of gasoline because it reminded her of car trips, of getting on the road.

She gave me that wanderlust, too. And it was probably also because of her that I mostly have lived in Chicago—now in the same neighborhood where I was born. She was a young (50) widow; I was her only daughter. It was not easy to not be close.

My mother always thought I was a good writer. When I was a kid and home from grammar school in the summers, she used to give me writing prompts, and we would read the stories I wrote when she got home from work. She had a favorite that we joked about the whole rest of her life, it was the story of a cat with blue ears. That’s all I’m gonna say about that.

When I was an adult and a writing student, and then a writing teacher, her prompts were to help her with her travel writing. I did guidebook work under her direction, co-authored a number of magazine articles. I helped her write the last article she did while she was recovering from chemotherapy; she stretched out on the couch in her office and had me read it to her as I made new sentences on the computer.

She’d be proud, I think. A little irritated, maybe, because I tell the darkness, too, as you mentioned. But proud. Mostly proud.

CR: The prompt on your blog kicked that first chapter of Swarm Theory out of me…like mother, like daughter.

In “I Go On Running” you talk about your love of running and its connection, for you, to process. You’ve had some injuries that have kept you from running. Has (or not) this influenced your writing process in any way?

PM: I miss running sooooo much! I was always more of a jogger than a runner, very slow, but it was absolutely part of my process. I ran in the quiet (no headphones) and listened to my breathing, to the world around me, to my thoughts. I ran for about three decades. And then last year I had to have my hip replaced. I walk now, fifteen to twenty miles a week or so, but it is not the same. Walking is lovely, meditative, healthy, but I miss the endorphins and the extra miles I could cover while jogging.

I know people who were smokers, who used smoking as part of their writing process. Write a bit, thoughtfully pull on a cigarette, stare at the computer through the smoke, write some more. They quit, and their writing stopped for a time, too.

I hadn’t really thought about how no longer running has affected my process, but I guess it has. I wasn’t able to run for a few months before the surgery; even walking was crazy painful. I am close-ish to the end of a draft of a novel, but I have been here in close to the same spot among these pages for about a year now. I have done other things—this collection, the essays for you, a little writing for hire, interviews, promotion—but I haven’t sunk deep into the novel—immersed myself in the story for days at a time, for pages and pages—in a very long while. About the same long while since my surgery, since the running stopped altogether.

Damnit! Does it influence my writing process to not be running? God damnit, I think it does. Now I just have to change that.

Find all things Patricia Ann McNair HERE and more about Side Street Press HERE.